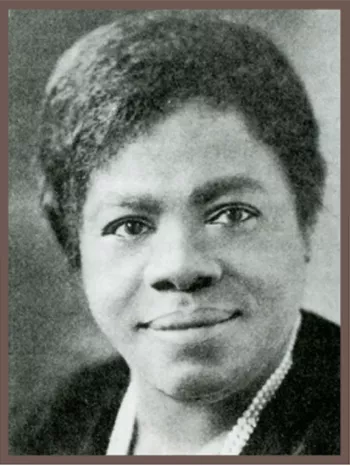

In 1904, with $1.50 and five young students, the now-legendary Mary McLeod Bethune started a school for Black girls in Florida that became today’s Bethune-Cookman University. Two decades later, Bethune was elected president of the American Teachers Association (ATA).

It’s women like Bethune—and NEA’s first female president, Ella Flagg Young—whose stories fill the pages of NEA’s rich archives. But their courage, persistence, and passion for the rights of girls and women isn’t just an artifact of the association. Their example continues to inspire NEA members and leaders today.

ATA and NEA merged in the 1960s. Today, as the nation celebrate’s the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote, NEA is taking a look back to celebrate its long history of phenomenal women leaders. Their history of fighting for equal pay and promotion for all women and for a high-quality public education for all girls remains a model for the union—and our nation.

In the beginning

At NEA’s founding convention in Philadelphia, on August 26, 1857, the association was still known as the National Teachers Association (NTA), and full membership was limited to “gentlemen” by the organization’s constitution. Women held “honorary memberships.” Nonetheless, the names of two Ohio women—principal Agnes Beecher and teacher Hannah Conrad—appear in an 1857 list of “original members” of the organization. Not 10 years later, in 1866, the constitution was amended by resolution, so that “gentleman” became “person.”

The “insurgents” win

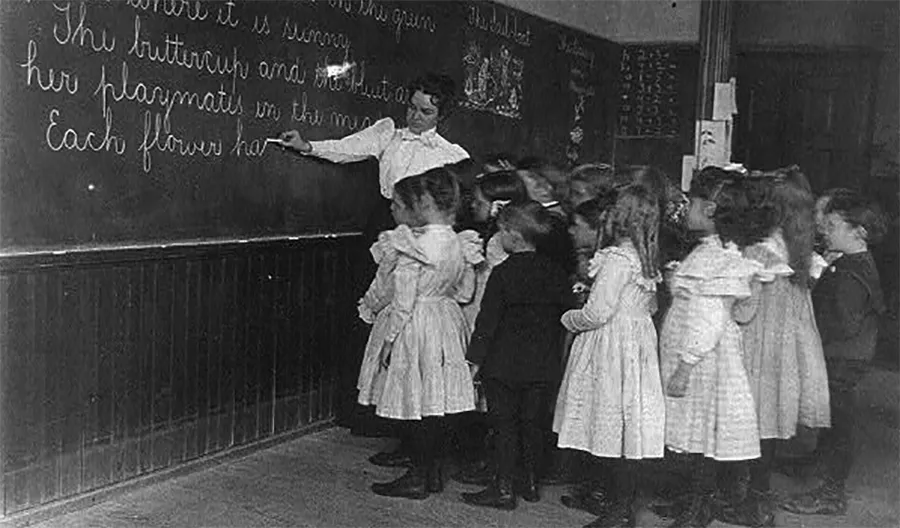

At the turn of the 20th century, the nation had about 420,000 teachers—three-quarters of whom were women—but their association, now called the National Education Association, was dominated and directed by a cabal of male superintendents known as the “old guard.”

In 1890, women began demanding a bigger role and that attention be paid to the concerns of classroom teachers. Dur- ing an association meeting in 1910, angered by an attempt to remove a trustee, women took control. They rejected the nominating committee’s report and elected Young as president.

“Insurgents Claim Complete Victory,” announced an NEA headline, preserved in NEA archives.

Before winning NEA’s presidency, Young had been the first female superintendent of Chicago schools, had organized teachers’ councils to give teachers a voice in their workplaces, and had served as Illinois Education Association president.

Meet Cornelia, Fannie, Mary, and others

Just two years later, in 1912, Bethune became ATA’s first woman president. Born during Reconstruction to parents who had been enslaved, Bethune grew up walking five miles to a Presbyterian mission school where a teacher noticed her dedication and recommended her for a college scholarship—setting Bethune on a path to change her career and the world.

After serving as ATA president, Bethune would be appointed director of African American Affairs by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and later found the National Council of Negro Women.

And the list of accomplished women in NEA and ATA history goes on. Cornelia Storrs Adair—a Virginia teacher who made sure her colleagues would have equal pay and retirement benefits—served as NEA president from 1927 – 1928. And Fannie C. Williams—a New Orleans educator who trained teachers and established early education programs for Black children in New Orleans—served as ATA’s president in the early 1930s.

More contemporary NEA presidents include Mary Hatwood Futrell (1983 – 1989), a Virginian who attended and first taught at all-Black schools. She accomplished so much as NEA president that NEA delegates amended their consitution so she could serve three terms.

And, of course, in 2014, delegates to NEA’s Representative Assembly elected the first, all-female, all-minority team to head the nation’s largest union, with Lily Eskelsen García as then-president, Rebecca B. Pringle as then-vice president, and Princess R. Moss as then- secretary treasurer. This summer, as Eskelsen García finished out her final term, Pringle was elected president and Moss vice president.

What’s changed, what hasn’t …

We’ve come a long way since the days of Bethune and Young, but we still have a long way to go. Today, 76 percent of public school teachers are women, according to federal statistics. And, likely because the profession is still viewed as women’s work, they remain undervalued and underpaid. Nationally, teachers are paid 21.4 percent less than similarly educated and experienced professionals—it’s known as the “teacher pay penalty.”

The more an occupation is dominated by women, the less it pays, studies show. Overall, across all professions, American women are paid 80 cents for every dollar paid to men, but the disparity is worse for women of color. Black women earn 61 cents for every dollar paid to white men; American Indian women earn 58 cents; and Hispanic women earn 53 cents.

“In schools across America, we tell girls they can be anything they want. They can run schools. They can run companies. They can run for president. But women still can’t get paid for the value of our knowledge, skills, and talents,” said former NEA President Lily Eskelsen García in 2016. “We must use all our fire power to change the way things are. After all, the old saying goes that, ‘Women hold up half the sky.’ It’s about time we got equal pay for it.”