All the Books for All the Kids With Kwame Alexander

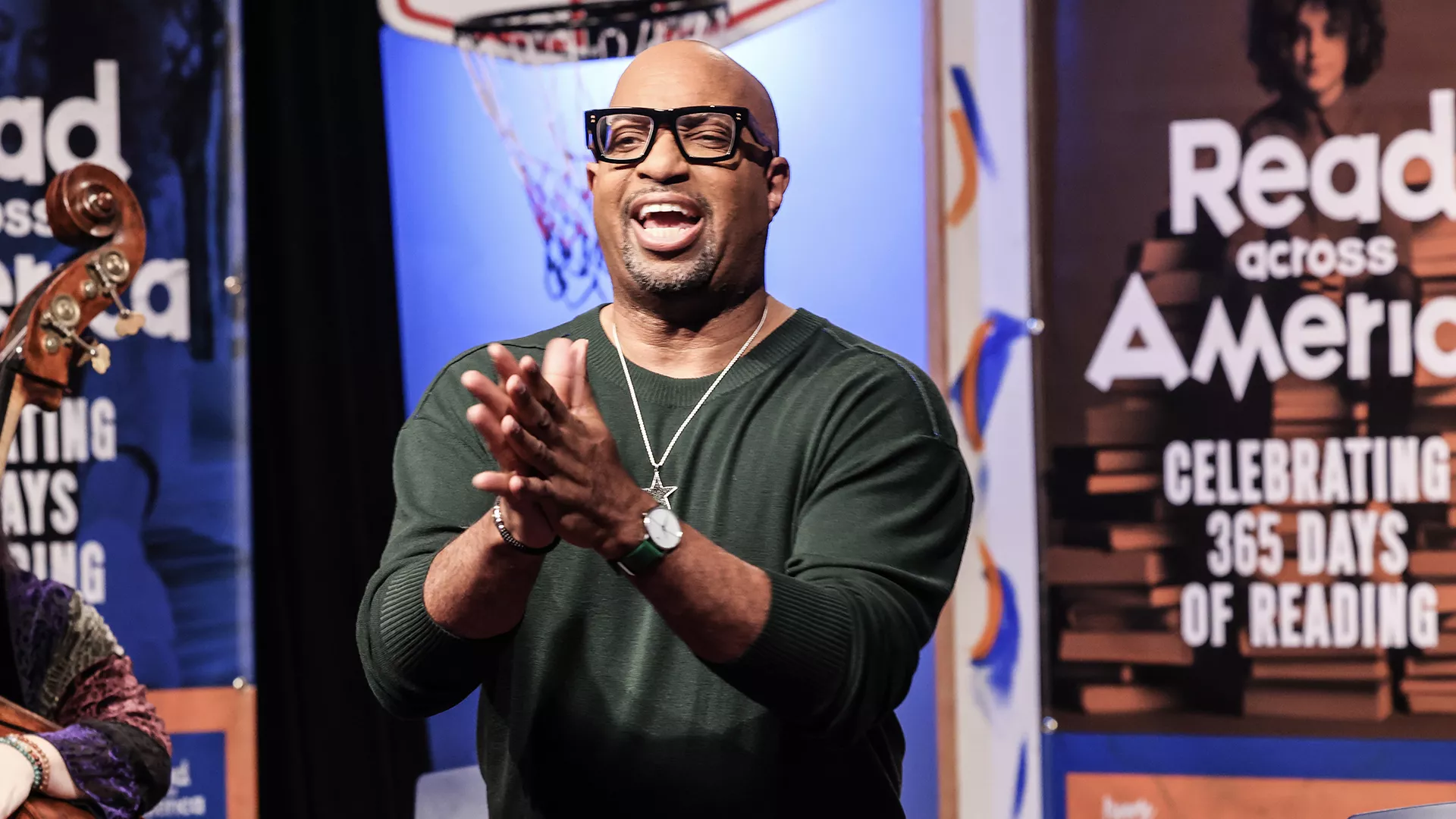

Jati Lindsay

Jati Lindsay

Section with embed

In celebration of NEA’s Read Across America, Kwame has teamed up with NEA for a unique project—bringing literature and music together with a jazz-infused reading of The Crossover. You can hear Kwame’s special 10th anniversary reading at https://www.nea.org/crossover.

Transcript

Transcripts are auto-generated

Kwame (00:02):

My position has always been that, as Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop has said, "Books are doors, books are windows, and books are sliding doors," and so it's important for us to be able to have access to books that represent the kind of place we claim we want in America. All the books for all the kids.

Natieka (00:22):

Hello and welcome to School Me, the National Education Association's podcast dedicated to helping educators thrive at every stage of their careers. I'm your host, Natieka Samuels. Today, I'm thrilled to be joined by a very special guest, Kwame Alexander. He's a poet, educator, and bestselling author of The Crossover, Booked, The Door of No Return, and so many other books that have inspired young readers across the country. His work brings literature to life through poetry, rhythm, and storytelling, and he's a passionate advocate for making reading joyful and accessible for all kids. In celebration of NEA's Read Across America Week, Kwame has teamed up with NEA for a unique project, bringing literature and music together with a jazz-infused reading of The Crossover. You can find us on YouTube, Facebook, and nea.org to find these videos as they release throughout the next week. Thank you so much for joining us today, Kwame.

Kwame (01:17):

Thank you for having me.

Natieka (01:18):

All right. Let's get started with, I guess, a bit of a bio. Can you tell us a bit about yourself and the work that you do?

Kwame (01:25):

I'm a father, a newly grandfather. I have a six-month-old grandson named Langston, and recently, after having spent quite a bit of time with him, I've decided I really need to focus my life. I need to get serious about my business. Of course, having written 42 books-

Natieka (01:48):

That's not serious enough?

Kwame (01:49):

Yeah, right. I just love my job as a poet, as an educator, as a television producer. I love all the things that I do that bring me such joy, but I think that I'm realizing now that the thing I really love the most is trying to figure out how to be a better father, son, grandfather, friend, man.

Natieka (02:12):

We're here today to talk a lot about reading, and as you just mentioned, you've written many, many books and you spent a lot of your career helping young people connect with books. What sparked your own love of books, and the words, and reading growing up?

Kwame (02:31):

Well, my parents were writers, and my mother read to us from the time I can remember. I can't remember a time that books weren't on every shelf in our home, in our bathroom, in the backseat of our car. Growing up with two writers, books became a reward and a punishment. Just being surrounded by words from a very early age, I knew how powerful they were, how cool they were, and I consciously made a decision when I went to college to get as far away from books as possible because I was sick of them. Of course, I took a class called Organic Chemistry on my way to becoming a pediatrician, and that quickly changed my mind about becoming a pediatrician. I found my way back to books, these things that I had loved and knew very well.

(03:28):

Books, and reading, and literature were a part of my life in the same way that eating and breathing were a part of my life. They just were a matter-of-fact thing. You read, you write, you figure out a way to use your words to find your voice, to become more confident. Ultimately, my parents have said this, their children were an experiment. Me being one of their children and they're firstborn, I was sort of the first experiment. How can they create an adult that uses his words to change the world?

Natieka (04:04):

Well, it seems like they succeeded. I'm actually curious what you liked to read when you were growing up.

Kwame (04:10):

Well, it depends on what age. When I was three and four, it was Dr. Seuss, it was Fox in Socks. As I got a little bit older, it was poetry, probably a little bit less whimsical, Nikki Giovanni and Langston Hughes. My favorite book was Spin a Soft Black Song maybe as a five and a six-year-old, which was a poetry book by Nikki Giovanni. As I got even older, books became kind of boring and uninteresting to me because my father began to buy me these encyclopedias, which were interesting to refer to every now and then but not as sort of go to your room and read the encyclopedia. He wanted me to read his dissertations from Columbia University, and that was not cool.

(04:59):

As an 11 and a 12-year-old, I just wasn't too interested in reading the kind of books he wanted me to read, but I had to because he was my father, nor was I interested in reading the kind of books my teachers and librarians were making me read, so it became sort of this battle. "I'm not going to read these books and I'm not interested in reading your books," and so books became uncool. It took me a while to find my way back to a love of books, and that came through poetry. Pablo Neruda, more Nikki Giovanni, Lucille Clifton, more Langston Hughes, more of the poets from the Black Arts Movement. Poetry is where I started and poetry is where I reunited with my love of reading.

Natieka (05:42):

Yeah. I think that's a pretty common experience, where either through school or, in your case of your parents, being forced to read kills that excitement about reading for a little while, and then you rediscover it, hopefully, later. I know that you're a big advocate for kids now, kids learning to read on their own and learning to love that. Why do you think it's so important for kids to enjoy reading on their own, and what do you think that families and educators who are listening, what can they do to encourage that?

Kwame (06:15):

It's real simple. I think a book is an amusement park. When your kid goes to Kings Dominion, or Busch Gardens, or Disney World, and they pass by the roller coaster or Space Mountain and they say, "Oh, wow. I want to do that," you don't stop them and say, "No, you shouldn't do that. You can't do that. You should go do the swings over here." That's not how it works. Allow the kid to choose the ride they want to go on and they might want to go on it again and again. Let them explore that. I think the same thing applies to books. Let kids choose the books they want to read. It's real simple. It ain't deep. Don't force them to read a book because they are supposed to be reading. Let them go on the ride they want to go on so that they can develop a want to read, a want to take that journey.

Natieka (07:05):

NEA's Read Across America program is something that we to talk about her and it's a big focus of our time today. Read Across America celebrates books and readers, but at its core, it's also about the joy of reading. What do you think that we are missing when we talk about literacy and how can we move the conversation forward?

Kwame (07:29):

We're missing the fact that it's less important to get kids reading and more important to getting them to want to read. The question is how do we get them to want to read? I know one of the ways that worked on me was poetry. Poetry became a bridge, this sort of very short, rhythmic, engaging, interesting language that I could complete a whole poem in 30 seconds or one minute. That built confidence in me, allowed me to keep going and wanting to read more. I think teachers and educators are afraid of poetry because of how we were taught it in school. It was boring, and incomprehensible, and staid. I think I try to write books that are going to be the opposite, that are going to be interesting, accessible, and smart, entertaining, but ultimately, engaging in a way that I think will help develop avid readers. Yeah, I think poetry may not be the answer, but it's an answer that has worked for me and that's the answer I'm going to really encourage teachers to embrace, which is why I try to write novels in verse. Natieka, poetry is the missing ingredient.

Natieka (08:54):

I feel like a lot of people are intimidated by poetry. It can be welcoming because it's short, but I think some people think of it as very high-minded and hard to understand too. But I think, at a kid's level, I think it's beautiful to be able to complete something in, like you said, 30 seconds.

Kwame (09:09):

Yeah. I mean, if you go from Shel Silverstein to Shakespeare, of course, it's hard. That's a huge divide. We need a bridge to get us there. I try to write books that are bridges.

Natieka (09:19):

What advice do you have for families, parents, caregivers, guardians, who want to make reading a bigger part of their children's lives?

Kwame (09:29):

Read with them, read to them. I read to my six-month-old grandson. My mom read to me, I read to my daughters, I read to my daughters before they were even born. I read to them in the womb. Establish a culture of reading in the household. Just real simple, the read aloud. Just read together. You don't have time for a whole book? Read a poem. Parents are tired in the evenings. I get it, they exhausted. Read a poem, read a haiku, take turns reading the haiku in different voices with different pacing. Just read, read aloud. That's my advice. Just start there. Once a day, once a week, make it a habitual. Let it be contagious and see where that takes you. I posit that it will take you somewhere magical, and meaningful, and majestic.

Natieka (10:26):

Something we talk a lot about in the Read Across America world is diverse readers and also diverse books, so how do you feel about this concept of diverse books?

Kwame (10:37):

I'm not a particular fan of using that language because of so many implications, but I would ask you to define, what are you asking me?

Natieka (10:45):

How do you think we should be talking about books and representation in a way that actually resonates and defines the terms?

Kwame (10:54):

Now you're cooking. I think all the books should be for all the kids. I grew up with the Everett Anderson Series by Lucille Clifton. I grew up with Uptown and Stevie by John Steptoe. I grew up with Moja Means One and Jambo Means Hello by Tom Feelings. I grew up with Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ear. I grew up with M.C. Higgins, the Great: Virginia Hamilton. Every book on shelf was a Black author. I had hundreds of books, so this notion that there are no "diverse books", that doesn't apply to me. That's why I ask when people say that, what are they talking about?

(11:33):

Are they talking about white kids should have more access to Black books, Black-authored books, or books of Black characters? Are they saying that Black kids should have more books to represent them? Are they saying that Black kids should have more books with white characters? Let's be clear what we're saying. My position always been that, as Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop has said, "Books are mirrors, books are windows, and books are sliding doors," and so it's important for us to be able to have access to books that represent the kind of place we claim we want in America. All the books for all the kids.

Natieka (12:15):

Windows, mirrors, adventure parks.

Kwame (12:17):

All the metaphors, my friend. All the metaphors today.

Natieka (12:21):

I want to talk to you a bit about book access and censorship. You've been pretty vocal about the importance of book access and pushing back on the growing wave of censorship that's resurging now. What would you say to educators who are really facing these book bans and restrictions? Of course at this time, we're seeing even more restrictions on what can be taught and how things can be taught. But since we're focusing on books today, what should educators and families keep in mind as these book bans are coming to their communities?

Kwame (12:57):

In my mind and in my life, this is nothing new, that books in fact have been banned and Black literature has been censored. Since I was a kid, I don't remember any teacher, K to 12, public school, ever having a Black book, a book written by a Black author, or a book featuring a Black character in the classroom other than maybe Sounder, maybe that was the only book I've ever remembered. I don't remember any picture books in elementary school. I don't remember any novels in high school. I remember The Good Earth, I remember Tuck Everlasting. I remember Treasure Island. That is a de facto banning and a censorship. When I think about how that was dealt with in my community, my parents protested it.

(13:51):

I remember bringing things fall apart by Chinua Achebe to school and my teacher telling me, "You can't read that for AP Lit." But I think how it was combated is that there were books in the home. You can't censor books in my home, and so my parents made sure that we had access to all the books in our home. One of the things I say to parents is, "Yeah, we resist, we protest, we go to the school board. It means we do those things that are necessary for the integrity of our education system and we make sure our kids have access to the books, because nobody can ban and censor books on the bookshelf." There are so many independent bookstores, and so many amazing public librarians, and public libraries that have these books.

Natieka (14:41):

Writing is obviously a big part of your life, and I've heard you say in other interviews and spaces that if you want to write or rap, for example, you have to read, so how do you feel that poetry and storytelling help young people develop their voices for any of the creative endeavors that they want in the future for themselves or now?

Kwame (15:02):

Well, I think writing is almost a prayer-like exercise in the sense that you are having a conversation with yourself about something that matters. I think, in much the same way, that we communicate our thoughts, and feelings, and concerns with people that we love and people that love us when we have these moments of conversation with people in an effort to get to someplace, to find some answer, to have some sort of resolution. I think when we are talking with ourselves, we are doing the same thing, that we are trying to get to a better understanding of ourselves. I believe that really is what writing is. We are talking to ourselves, we are talking with ourselves. We are having a conversation about something that is important, and significant, and something that matters, and that perhaps when we get to the end, we have some sort of better understanding, some resolution, and I think that ultimately helps us become a better human being.

Natieka (16:18):

Thanks for listening to School Me, and a quick thank you to all of the NEA members listening. If you're not an NEA member yet, visit nea.org/whyjoin to learn more about member benefits. This year, you're teaming up with NEA for a special jazz-infused reading of The Crossover, and it's also the 10th anniversary of The Crossover.

Kwame (16:39):

Oh, The Crossover winning the Newbery Medal. Yes.

Natieka (16:43):

Great. What inspired this project? What do you hope kids are going to take away from hearing this collaboration of music and words?

Kwame (16:53):

Well, what inspired it was I woke up one morning, Natieka, and I was like, "Ooh, I should read The Crossover, the entire book." I texted Rachel at the NEA, I said, "I want to read The Crossover every day. You all want to be involved?" This was all in the same hour. I hadn't even thought it through. She got back to me and she was like, "They're on board. The NEA wants to do it." I was like, "Oh, well, this is going to be a lot of work," but it was too late then because everybody was on board and they were designing sets. I backed myself into this corner that ended up being really hard to execute in front of a live studio audience, 238 pages, and keep their attention, and keep them interested, and engaged. That's how it happened, but my inspiration for wanting to do it was to say thank you to the readers, to the fans, to the students, to the librarians, to the teachers.

(17:57):

Thank you all for supporting this book. Thank you to the millions of readers who have bought this book. To all the gatekeepers, the librarians, and the teachers who made sure this book was in their classrooms and in their libraries, to all the parents who bought the book for their kid, and to all the kids who read a book for the first time and it happened to be The Crossover, this was my way of saying thank you. I'm going to give something to you all, and hopefully, you all will enjoy it. I'm going to read the book to you. I think involving Amy Shook, the bassist, incorporating some jazz music, I thought it made sense because there's so much jazz in the book and I was listening to so much jazz when I was writing it. This is really a thank you to everyone who's supported The Crossover over the past 10 years and a way to do something interesting and fun for students in the classroom.

(18:46):

To celebrate the 10-year anniversary of The Crossover winning the Newbery Medal, we decided to do a number of celebrations and activities. The NEA Read Across America x Kwame Alexander Reading of The Crossover from March 3rd through the 7th, Monday through Friday, is our kickoff. That's our big launch for this whole year-long celebration. The next thing we're doing is a thing called the Kwame Alexander Youth Games, and that's like an Olympic-style event happening in my hometown of Chesapeake, Virginia. That's April 9th through the 11th. It's a free throw shooting contest. It's an invitational tennis tournament because tennis was my sport in high school. It's an invitational tennis tournament between Great Bridge High School in Chesapeake, Virginia and Cox High School in Virginia Beach. It's the girls varsity teams playing.

(19:40):

The biggest thing that I'm excited about is the Battle of The Crossover Books competition. It's where elementary and middle schools will compete in a jeopardy-style trivia contest centered around my books. There are three teams competing from lower and middle school, and each school has a lifeline they can call. I'm bringing in a couple of authors to help out with that trivia contest, Jean Yang and Jerry Craft, so I'm excited about that. The last thing that we're doing is we're partnering with Little Free Library, and we are having some Crossover-themed little free Libraries that are being built that'll be donated to six lucky communities around the country. I'm just excited to celebrate this book and all the people who've enjoyed it.

Natieka (20:30):

The Crossover has been a game changer for a lot of young readers. It's a graphic novel and a TV show. Why do you think that this particular story has resonated so deeply for this audience over the last decade especially?

Kwame (20:46):

I've thought about that a lot. I was in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and the seventh grader named Shunwell, he's probably a senior or in college now, he wrote me a letter. His librarian gave it to me at the library event that night. I read the letter the next morning, and it was a two-page letter on how he had never read a book and how he couldn't put The Crossover down. He loved it and thanked me for writing it, and he couldn't wait to read more books. I found out what school he went to and I surprised him that morning at his school. He just went running up and down the hall, like screaming, "Kwame Alexander's here." He was so excited. I tried to write a book that I would've wanted to have read when I was his age, that I wouldn't have wanted to put down, that I love now. I tried to write that kind of book.

(21:39):

My hope is that when I write something that is meaningful, and significant, and that I enjoy immensely, that others will too. What they find in it that they connect with, that they find something to connect to, that is my hope. What that something is, no idea. But I do know that when I read Spin a Soft Black Song, "Come Nataki dance with me, Won't you sing and dance with me," a poem by Nikki Giovanni when I was six years old and my mother was pregnant with her third child, I said, "Mom, if she's a girl, you got to name her Nataki," because I know I love that poem and I just recited it over and over.

(22:22):

I know the impact that poetry had on me, and it just tapped into all of my emotions. It just made me feel good and it made me feel complete. I could get through something really quickly and feel a sense of like I did something. I know those feelings that I had when I read Langston Hughes as a kid, and when I read "fox, socks, Knox, box", Fox in Socks, socks in box, I know those feelings. Maybe it's the poetry that resonates with readers and it makes them feel something quickly, that immediacy of emotion. I don't know what it is, but I'm glad there is something.

Natieka (23:03):

I'm actually curious about what you think about this. I recently heard someone talk about how when an author creates something, when they write a book, when they write their poetry, whatever it may be, that once they put it out in the world, it no longer belongs to them anymore. It belongs to the audience, the readers, to give it meaning or not or interpret what it is. How do you feel about that view of once you put your art out there, it's maybe not about you anymore?

Kwame (23:36):

The writing was about me, that journey of me writing it. The publishing of it, that's for you. I had my time with it, and it challenged me, and I loved it. There were days where I doubted it, and there were days where I didn't know if I could do it, and there were days where I was like, "Oh, this is amazing." I ran through that whole journey with it and loved it ultimately, and then I published it and now it's your journey.

Natieka (24:04):

For anyone who has not read The Crossover, I'd like to entice them to tune in to the reading that you're going to do, so can you give a little bit of a summary for anyone to get them excited about hearing it in this new way?

Kwame (24:21):

It's a novel about brothers, twins, who are stars on the basketball court and stars off the court. They've got a mother who's an assistant principal and their father who's a former basketball player, and he thinks he's the coolest, funniest dad ever. There's this really just beautiful family thing happening. One of the brothers decides he wants to do something different and his twin brother doesn't understand. "We've been the same forever. We've been tight, we've been best friends forever." He doesn't understand how his twin is moving in a different direction now, wants to do new things, wants to be more independent. You can tell these brothers apart because one brother has long hair and one brother has no hair. That's the way you can tell them apart.

(25:01):

One day, the brother with no hair bets his brother if he makes the final shot in the game, he gets to cut off all his brother's hair. His brother responds, "If my hair were a tree, I'd climb it. I'd kneel down beneath and enshrine it. I'd treat it like gold and then mine it. Each day before school, I unwind it, and right before games, I entwine it. These locks on my head, I designed it. One last thing, if you don't mind it, that bet you just made, I decline it." That's some of the rhythm and the verse of how I tell the story, and that's also the moment in the story where their relationship begins to have a strain and where there's no turning back from where they're both headed, because they're crossing over from becoming children into young men.

Natieka (25:51):

Overall, do you have something that you're trying to communicate to, I'd say, the young people, but for anyone who's picking up your books, do you have an idea of a lesson that you're trying to teach them or is it more organic than that when you write?

Kwame (26:06):

Definitely a lesson. I'm always teaching something, absolutely.

Natieka (26:09):

What is your favorite lesson to teach when you write?

Kwame (26:12):

No. If I were to tell you that, what would be the point of me writing the books, Natieka. I learned long time ago not to try to tell then just show, because a lot of times, I think these kids don't even know that they're learning something by reading these books, and I'm fine with that.

Natieka (26:32):

Maybe it's better that way.

Kwame (26:33):

Right. Maybe it is.

Natieka (26:35):

Why do you like to focus so much of your writing on the experiences of young people or at least talking to them?

Kwame (26:43):

My first 13 books were for adults. When my second daughter was born, then I began writing poems for her and my sensibilities changed. As she grew and grew, I began writing for her and her friends. It was purely a matter of circumstance and really trying to inspire, and encourage, and empower my daughter and her friends. But generally, I like to think I write about kids, but I write for all of us. I try to write books. Whether it's How Sweet the Sound, or The Crossover, or the Undefeated, I try to write books for all of us that kids and parents, students and teachers are going to enjoy it and get something from.

Natieka (27:26):

Can you talk a bit about Author Study?

Kwame (27:29):

Since 2014, I've been on the road pretty much a couple hundred times a year, visiting schools, doing author visits, reading from my books, answering questions, signing foreheads all around the world, K to 12, and have loved it. Inevitably, there are going to be some schools who can't afford to bring me or I'm not able to reach as many students as I would like to because I'm only one person, and so I began to think how to scale up this initiative, this effort, to get in front of students and to encourage a joy and a love for reading. I came up with this idea of a, during COVID, we could not go to schools, and so we began to do virtual visits. I noticed in the first couple virtual visits that kids were bored or they weren't used to this. Obviously, none of us were.

(28:30):

I began to figure out little tricks, and tips, and things to do to make virtual visits engaging and exciting almost as much as my in-person visits, and it began to work. I'll give you an example. A little thing I would begin to do at the beginning of each presentation and throughout during virtual is, when you're on Zoom, obviously, there's a chat function. A lot of people were closing the chat functions because you could get all kinds of weird, and crazy, and inappropriate things happening. There's also a participant tab and you can see who's logged in. I would use one or both of those, and at the beginning of each of my Zoom talks, I would begin to shout out people. "Hey, what's up. Natieka from Farmville, Virginia, I see you. Yo, I've been to Farmville. There's a college there called Longwood University."

(29:24):

I began to call people out and share different information about my connection to their school or their city. Oh my gosh, you would've felt like it was just me and one school having a conversation, because I would get emails saying, "Thanks so much. We loved your thing you did for us." It was 1,000 schools on a virtual. It was so many schools on these different virtual things at one time, and they felt like they were the ones. I said, "Well, this is interesting." In addition to doing individual school virtuals, I can do larger virtuals and invite multiple schools. The idea came, "Well, why don't I just make that a thing?" and so we created Author Study where schools can register, for a little nominal fee, a fraction of what it would cost to bring me in person. We would do a 40-minute reading, mini lesson, surprise guest author interview, and Q&A. It just took off, and so we started doing that. I guess we've done about 10 of them. We do about four or five a year. Authorstudy.com, check it out.

Natieka (30:34):

I think you're always working on something exciting, so can you share what's next, what's coming up for you? We just heard a lot about The Crossover, but is there anything else that you're working on right now that you're really excited about?

Kwame (30:47):

I wrote a book with Jerry Craft. It's called J vs. K. It's about two fifth graders who are rivals. They're competing in the school-wide creative contest, and they realize that it's probably better if they come together. The book is really about how they can figure out if their egos, if their talents, if their animosity towards each other can wane and they can come together. It's sort of based on a fake rivalry that Jerry and I have, because in actuality, we're pretty good friends. I'm excited about that book. We'll be doing a tour around the U.S., the J vs. K book. That's May 6th. I'm really excited about that, and then I have a cartoon coming out on PBS based on one of my... On my first children's book I ever wrote, Acoustic Rooster and His Barnyard Band, which is about a rooster that starts a jazz band with Duck Ellington and Miles Davis, that cartoon debuts sometime in May, so tune into Acoustic Rooster.

Natieka (31:53):

Okay. Well, it's been such a pleasure to get to talk to you today. Thank you so much for joining us.

Kwame (31:58):

I am really humbled and honored at the legs that The Crossover has. I never expected to win a Newbery medal. I never expected to adapt The Crossover into a Disney Plus TV show. I never expected to be in the development stage of a Broadway musical based on The Crossover. This book, this book that I wrote in 2008, it's just incredible to see it's still on its journey. I think this effort with the NEA is a great way to pay tribute and honor this book, that, again, no longer belongs to me. It belongs to the students who have and who are reading it. It belongs to the teachers who are teaching it. I love being able to say thank you all for that, and what better partner to do that with than the NEA. Thank you, Natieka.

Natieka (33:04):

Thanks for listening. Make sure you subscribe so you don't miss a single episode of School Me, and take a minute to rate the show and leave a review. It really helps us out and it makes it easier for more educators to find us. For more tips to help you bring the best to your students, text POD, that's P-O-D, to 48744.

References

Join Our Movement