70 Years of Brown v. Board

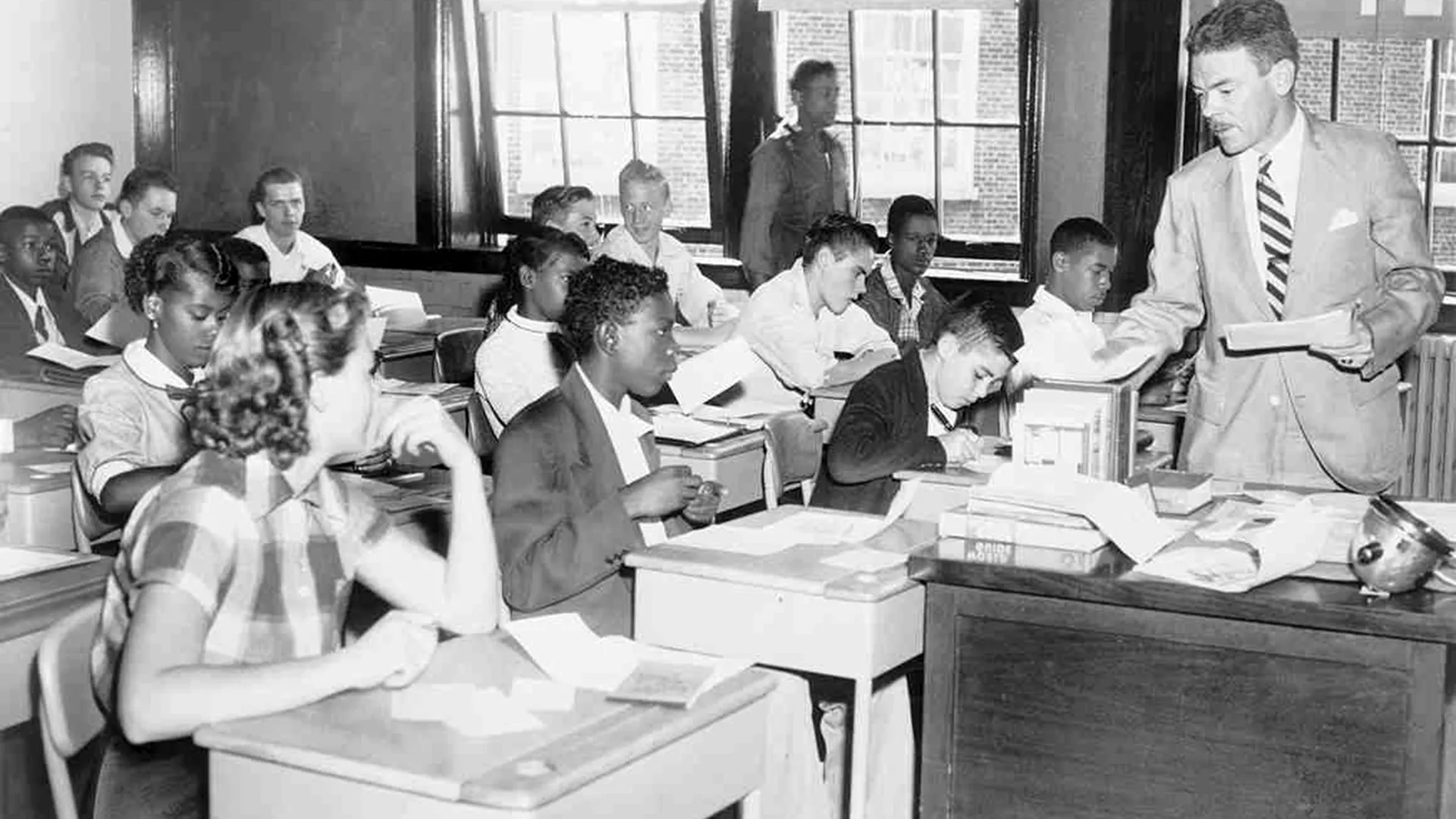

Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

Section with embed

It's been 70 years since the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. For many, this iconic Supreme Court case feels like a foundational and permanent part of American society, but today, the promises of Brown v. Board are under attack. Danielle Davis, Staff Counsel for NEA, joins the show to discuss the impact of this important ruling on America and what the future holds for the promises of that case.

Transcript

Transcripts are auto-generated

Danielle (00:02):

Diversity doesn't just benefit black students and other students of color. It has long-term positive effects on the health of our public schools, and I think arguably the health of our country, the health of our democracy.

Natieka (00:19):

Hello and welcome to School Me, the National Education Associations podcast dedicated to helping educators thrive at every stage of their careers. I'm your host, Natieka Samuels. May 17th, 2024 marks 70 years since the US Supreme Court issued its landmark ruling in Brown versus Board of Education. For many, this iconic Supreme Court case feels like a foundational and permanent part of American society, but today, the promises of Brown v. Board are under attack. My guest today is Danielle Davis, staff counsel for NEA. Together we are discussing 70 years of Brown v. Board in America and what the future holds for the promises of that case. Thank you so much for joining us today, Danielle.

Danielle (00:59):

Thank you for having me.

Natieka (01:01):

So let's talk a little bit about you and your position at NEA.

Danielle (01:05):

I'm currently one of the staff council in the Office of General Counsel at the National Education Association. I've been with NEA since September of 2021. So NEA is such a special place to work. I really enjoy getting to know my colleagues and having communication with and relationships with the folks who I'm advocating on behalf of.

Natieka (01:30):

So let's dive into our official topic of the day, which is Brown v Board of Education. So I think we should start with setting the stage of what the State of America was before the US Supreme Court actually gave their opinion on this case.

Danielle (01:49):

Yes, so excited to talk with you today about this case as we commemorate the 70th anniversary. Prior to Brown versus Board of Education, Americans essentially lived in an apartheid state. Which folks should understand or might understand to be a system of segregation and discrimination on the basis of race. There were several steps that this country took towards the system of segregation and discrimination. One of those steps came in the form of black codes, which were laws that were passed mostly in the American South, starting around 1865. And these black codes dictated most aspects of black people's lives, including where they could work, where they could live, and it ensured black people's availability for cheap labor after slavery was abolished. So fast-forward a few years, another major step towards the system of segregation were Jim Crow laws, and these were a series of laws that were passed again, mostly in the American South through which legislators segregated everything from schools to residential areas, public parks, theaters, pools, phone booths, jails, and even cemeteries.

(03:03):

This system of racial segregation and discrimination was also sanctioned by the United States Supreme Court in an 1896 case called Plessy v. Ferguson. I think it's fair to characterize this decision as repugnant and really disgusting. Essentially what the court did was sanction Jim Crow laws, laws that enforce racial segregation by finding that Louisiana's "separate but equal" law was constitutional. And this case which was really built on the notions of white supremacy and black inferiority, it really provided the legal foundation for America's racial caste system in which black Americans were second class citizens.

(03:48):

So that's the sort of backdrop to Brown versus board. I think it important to mention that despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Plessy and similar cases, that there were people who continued to press for the abolition of Black codes, the abolition of Jim Crow laws and other racially discriminatory laws and policies. An organization that we'll talk more about that was fighting during that time was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people, otherwise known as the NAACP. And it was the legal arm of the NAACP known now as the Legal Defense Fund or LDF that devised the strategy that was used to attack Jim Crow laws in the field of education. And that happened under the leadership of a lesser known attorney, Charles Hamilton Houston, and then a very well known attorney and later Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

Natieka (04:43):

So skipping forward to the case itself, what did the US Supreme Court rule in Brown v. Board?

Danielle (04:52):

In Brown v. Board, the court overturned Plessy versus Ferguson, first of all. And it unanimously declared that segregating students on the basis of race, even if the physical facilities and the educational resources are equal, is unconstitutional. Specifically what the court concluded is that in the field of public education, the doctrine of separate but equal "has no place." And that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal and thus violate the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause. This case is widely seen as a historic or landmark case, the case that began the end of racial segregation in America, certainly in schools, and a case that for the first time afforded black children access to the same educational opportunities as white children.

Natieka (05:48):

And how did we get there at all? So what led to the Supreme Court even making a decision on a case like this? Who brought the case and was it just one lawsuit or a combination of a few?

Danielle (06:02):

Sometimes people forget or maybe folks don't often know that this case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education was actually the name given to five separate cases that were heard by the Supreme Court, all concerning this separate but equal doctrine in public schools. And while the facts of each of those cases was different, each of them was brought by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund on behalf of courageous black students and their families. And the main issue in each of those cases was the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools. So when those cases were appealed to the Supreme Court in 1952, the court consolidated all five cases under the name Brown v. Board of Education.

(06:54):

Now, the Brown opinion wasn't issued until 1954. So two whole years later, when the justices first consolidated those cases and heard them in 1952, they realized that they were actually deeply divided on the issues that the cases raised and thus were unable to come to a decision by the end of that Supreme Court term. So what they decided to do was rehear the case the following year in December of 1953. Now, one sort of a history tidbit that's important here is that in those intervening months, the then Chief Justice of the Court, Chief Justice Fred Vinson passed away and was replaced by then Governor Earl Warren of California. And this is significant because what Chief Justice Warren was able to do was bring all of the justices together, resulting in a unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which was unusual even today and significant certainly for the time.

Natieka (08:01):

What sort of evidence did the court consider in this case?

Danielle (08:04):

As previously mentioned, there were multiple hearings in this case. Later as we know him, Justice Thurgood Marshall is the attorney who argued the case before the court and he raised a variety of legal issues on appeal. But I think what's important for the listeners is the central argument that he made and that was that separate school systems for black students and white students were inherently unequal and thus violated the equal protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. In support of this central argument, he presented the results of a series of experiments which folks might remember.

(08:43):

They're commonly known as the Doll Test. I have a visual in my mind, a video I remember watching where they showed black children and white children and they had little baby dolls in front of them. When asked them, which one do they prefer? Which one's prettier, which one's smarter, right? These tests studied the psychological effects of segregation on black children and found that prejudice, discrimination and segregation created a feeling of inferiority among those children and damaged their self-esteem. So in light of those findings, I'll call him Justice Marshall argued that such a system would not be legally permissible and the court agreed.

Natieka (09:24):

So two years after the case first came onto the scene, it's 1954, the decision comes down. It's a very historic one. I think going through life right now, a lot of decisions don't feel historic. But when we think about the past, of course all we learn about are the major ones. So this major thing happens. So what is the immediate impact after the ruling comes down and how is it enforced and how long maybe did it take to get to actual enforcement?

Danielle (09:55):

I think it's accurate to say that the response to this decision was divided. People even then recognized the historical significance of it, and there were mixed feelings about it. I did find one quote from Harlem's Amsterdam News, which called Brown, "The greatest victory for the Negro people since the Emancipation Proclamation." On the other side, you had folks who we'll talk about later, went so far as to close the schools rather than integrate them. It was definitely a polarizing case, and change did not happen overnight. In fact, the Supreme Court waited more than a year to issue an order actually enforcing its decision in Brown. And even then the court was unwilling to establish a firm timetable for dismantling racial segregation. It wasn't until 1955 that the Supreme Court ordered the lower federal courts to require desegregation "with all deliberate speed." So unfortunate for the nation desegregation did not happen quickly.

(11:11):

It was neither deliberate, nor was it speedy. Instead, the court's directive was met with anger, often violent resistance by those school officials who I mentioned previously who closed the schools rather than integrate them by white mobs who rioted, who would show up to harass and scream at and spit on the black students who were integrating schools, right? We recall seeing videos of those horrible incidents and folks who essentially attempted to block the desegregation of schools and their community. Between 1955 and 1960, federal judges heard more than 200 desegregation hearings, and it actually wasn't until 1968 that the Supreme Court ordered states to dismantle segregated school systems "root and branch." There's a case, it's the case from which we draw what we call the green factors. So it was in 1968 that the court issued this decision and essentially said that there were five factors that courts had to use to gauge whether a school system's compliance was consistent with the mandate of Brown.

(12:24):

Those factors included the facilities, the staff, the faculty, extracurricular activities and transportation. But I think it's accurate to say that the promise of Brown or the mandate of Brown was never fully fulfilled. In the intervening years, civil rights attorneys have filed hundreds of lawsuits against school districts across the country in an attempt to vindicate the promise of Brown. And according to LDF, even today, more than 200 school desegregation cases remain open on the federal court dockets. So I think it's an open question as to whether or not the mandate of Brown was ever effectuated and if it was ever really enforced.

Natieka (13:09):

The promise aside, what actually happened? How would you say Brown has impacted public education over the past seven decades?

Danielle (13:19):

Well, it is true that in some parts of the country, schools were integrated and opportunities for students of color increased tremendously in large part because of the additional educational resources that they had access to. According to some research that I did in 1988, that is the year that school integration reached it's all time high, but that was even a mere 45% of black students in the United States attending majority white schools. So we hit all time high integration in 1988, but even that all time high was only 45%.

Natieka (14:00):

Right. I was actually going to ask what the sort of standard of integration is. Like, are we saying that there's one black student in a mostly white school or are we talking about 1% of students are non-white or black? That certainly was my experience growing up, but I grew up in DC, public schools where I think it's just a little bit more diverse depending on where you go. But what do you think is the definition of integration in this situation?

Danielle (14:31):

Unfortunately, I don't think that there is a commonly accepted definition. Instead, what a lot of civil rights advocates and legal scholars have been sounding the alarm about is actually the trend towards re-segregation. And the way that they define that are schools in which students are racially isolated. Where one race is a majority of the students in that school, in most cases we're talking about school districts in which black and brown students go to school with almost exclusively with other black and brown students, or in some cases students who are socioeconomically more disadvantaged. It's a really alarming trend that has been happening really since the '90s. But I think our inability to come to some consensus about what it really means to have diverse integrated schools is one of the ways that we've really failed to deliver on the promise of Brown.

Natieka (15:36):

That just struck me as a question to ask because you're talking about the height of desegregation in '88 and then two years later already resegregation begins. So we can go back to how you feel the case impacted public education even before '88 or after '88 or just any time over the last 70 years.

Danielle (15:56):

Yeah. One way of answering this question is also to talk about the ways in which Brown v. Board of Education impacted the broader civil rights movement in this country. I think it's pretty widely accepted that this case in particular was a major catalyst for the Civil rights movement. And following Brown, you have movements like the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, the sit-ins mostly at lunch counters in states across the south, mostly courageously done by students. You also have the 1961 Freedom Riders, and all of these movements which led to further bans on racial segregation in housing, in public accommodations, in institutions of higher learning. All of this really culminates in 1964 with the Civil Rights Act. This act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in public accommodations, in the workplace. It's important to the enforcement of many of the rights that we enjoy today.

(17:01):

I know myself probably take for granted, and this benchmark civil rights legislation, it really closed the door on the application of Jim Crow laws under the Plessy decision. So basically, if you don't have Brown, you probably don't have the Civil Rights Act, or at least you don't have it as early as 1964. So the significance of Brown can't be overstated. Brown also led to the eventual passage of laws like the Fair Housing Act, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits schools from discriminating against students with mental or physical impairments. So Brown was important to schools undoubtedly, but it also had a major impact on the movement for civil and human rights in the country more broadly.

Natieka (17:52):

Thanks for listening to School Me and a quick thank you to all of the NEA members listening. If you're not an NEA member yet, visit nea.org/whyjoin to learn more about member benefits. And were those changes happening because of a changing tide of sentiment among Americans or was it legal precedent that started to just break down other parts of society that were clearly segregated?

Danielle (18:22):

Well, I'm not a historian, but I think it would be accurate to say both end. We both had a change in sentiment across the country and mass movements happening, many led by students. And then you had very strategic sort of legal plan that was being effectuated by LDF and its attorneys as well as other civil rights attorneys who were sort of incrementally challenging laws, challenging policies, tempting to push the needle as it related to civil rights in the country.

Natieka (19:07):

So we've talked a little bit about how the promise of Brown has been, let's say, eroded over the past 70 years with resegregation and other things. So I wanted to talk some of the other things that we might be seeing or worried about, which I'd love to hear about the sorts of laws and policies that you feel have eaten away at the promise of Brown over the years.

Danielle (19:29):

Well, first, what are we talking about when we say the promise of Brown? I think it accurate to say that the promise of Brown was that all students, regardless of race, would have the same educational opportunities. What the Supreme Court proclaimed was that education is a right that must be made available to all on equal terms. And for many folks, brown was supposed to be the beginning of racial equity and education. It gave hope that all of the effects of the nation's previous apartheid regime would be remedied. Unfortunately, what we have seen is that even today, laws and policies and other systems that are mostly rooted in anti-Black racism continue to limit educational opportunities for millions of students nationwide. So despite the efforts of over the last 70 years, what we're now finding is that the majority of America's school children still attend racially segregated schools.

(20:33):

And I think we could point to a number of things, laws and policies, everything from voting to housing that have drawn lines based on race that have divided our communities. But this failure to uphold the promise of Brown by eliminating racially segregated schools, it has detrimental effects on the lives of students and arguably will have lasting consequences for our democracy in the way of some examples. What sorts of laws and policies have eaten away at those promise? Well, I think we have to start with decisions of the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, which have gradually back stepped limiting requirements for school districts, eliminating altogether programs that have been developed over the years to address the lingering effects and disparities that resulted from Jim Crow laws, right? And other forms of racial segregation. These trends towards more racially segregated schools is the natural consequence of redlining and housing and economic zoning policies which result in racially segregated neighborhoods and communities.

(21:55):

Add onto that, school closures, school redistricting, school choice policies, discriminatory transportation policies, and what you have is a system that works in tandem to increase racial isolation both in communities and schools. The other campaign that's used to undermine Brown is inadequate and inequitable school funding, right? If the promise of Brown was and is equal educational opportunities for all students, well then the way that we fund schools in America certainly undermines that promise. Then you've got, like we are seeing today in the way of attacks on diversity and censorship of educators, attacks on inclusive education, and this includes a number of things.

(22:51):

We've got the dismantling of race conscious admissions at the higher ed level, attacks on honesty and education, on racially inclusive education, on critical race theory, despite the fact that it's not taught in through K-12 schools. We've got the elimination of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility, otherwise known as DEIA programs and even prohibitions on advanced placement African-American studies. So I think it accurate to say that the campaign against Brown is one that's been going on for many decades and has been helped both by historical laws and policies, the impacts of which we are still experiencing to this day, coupled with new laws and policies that have made it increasingly more difficult for us to make our communities and our schools more diverse.

Natieka (23:52):

So I think when people think about Brown v. Board or affirmative action or any of these kinds of things, they think about the way that they benefit black people in particular, or people of color more broadly. But if we take that aside for a moment, how do we feel that white students have benefited from things like Brown or from DEIA programs or any of these things that sort of get put in a black category, but definitely don't just benefit us?

Danielle (24:26):

Yeah. There is a rape report that the NEA co-authored with the law firm, Anti-Racism Alliance on this very subject. But essentially it was a report sort of bringing together all of the empirical research that's been done over the years that shows that diversity in our schools culturally responsive and racially inclusive education, it doesn't just benefit black students or students of color, it benefits all students. And I think it accurate to say that the research has shown that when students are in these sorts of school environments in which they feel welcome, they feel safe, they feel seen, their community or individual identity is recognized and is part of the curriculum in which they have at least one black teacher.

(25:22):

Those students perform better regardless of their race. Those students perform better. They graduate at higher rates, they do better on standardized tests, and I think most folks agree they're better prepared for our increasingly global world. Diversity doesn't just benefit black students and other students of color. It has long-term positive effects on the health of our public schools, and I think arguably the health of our country, the health of our democracy, for this reason, I think it's so important for us to commemorate the anniversary of Brown, understand the significance of the case. But also recommit ourselves to the work that is necessary to be sure that the promise of Brown actually comes to fruition.

Natieka (26:14):

What are the dangers of today's Supreme Court's, conservative supermajority? Are we looking at a situation now where we think that Brown will be reconsidered or overruled by the Supreme Court, even though I think in the minds of a lot of people, this is sort of a foundational case for this country?

Danielle (26:35):

Unfortunately, yes, I think we are in danger that the supreme Court's conservative supermajority could reconsider Brown and or even overrule the case. And for evidence of that, I think we have to look no further than the confirmation hearings of some of the justices that were most recently added to the court. And when they were asked the specific question about Brown versus Board of Education, they refused to say that this case was binding law or that they wouldn't reconsider the issues in Brown. So that's really scary. I think also after the Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs in which the court reversed Roe v. Wade and declared that the right to an abortion is no longer a constitutional right. When they did that, they took a half a century of precedent and threw it out the window. So I think many legal scholars have questioned what other longstanding rulings of the court are in danger. To what extent is the Supreme Court bound by legal precedent and could Brown v. Board of Education be on the chopping block?

Natieka (27:53):

And what do we expect to be the effects of that? So we're seeing the effects of Dobbs right now and in the news all the time. Like what states are doing with their newfound ability to limit access to abortions. If Brown were overturned, and I guess it would depend on what the case actually was, but what do you think that we would see happening in the more immediate term if that were to take place?

Danielle (28:21):

Yeah, it's hard to imagine. I sort of shudder at the thought of it. I mean, on one hand, one might say that not much would change. We are already in a place where so many... One out of three high school students in America goes to a racially segregated high school. Another way to think about it however, is that Brown, yes, was very much about students and educators and public schools in this country. It also represents something much bigger than that, doing a way of racial apartheid in this country and a statement by the highest court in this land that this so-called separate but equal doctrine was BS, right? It's not constitutional and that we as a country are no longer going to operate in this way as a racial caste system. And I think what's more disturbing to me is to think about what it would mean for us as a country if this Supreme Court were to go back to that case and say, "Actually racial caste system. That doesn't sound too bad." Yeah, I don't know. But I hope that we never have to learn the answer to that question.

Natieka (29:32):

So perhaps on a positive note, let's talk about how NEA is doing its best to fulfill the promise of Brown.

Danielle (29:42):

Yes, we would be here for another 30 minutes, I think if we delineated all the ways that NEA and its members have been and continue to fight for the promise of Brown to be fulfilled. But I think it important to point out just a few ways that we're doing that work. Of course, we continue to fight for significant changes in law and policy, at the local level, at the state level, at the federal level, to reduce racially segregated schools and ensure that all students, regardless of race have access to equal academic opportunities. One of the areas that I work in, which is sort of unique, is that of judicial nominations. So one of the things that NEA does is oppose judges or attorneys who have been nominated to be a federal judge who declined to support the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown. Other ways that NEA is working to fulfill the promise of Brown include fighting for adequate and equitable school funding so that all students have the funding they need to learn without limits and so they can unlock their dreams.

(30:57):

Another thing that NEA supports are community schools which create communities that are racially just, that are caring, that nurture and value the assets of each child while building trust and community. Emphasizing that these communities consist of educators along with school board members and community partners, parents, caregivers, students, and it's this collective community that's needed to resolve many of the challenges that we have identified today. I think to the extent, listeners are asking themselves, what can I do? What can I do as an educator to attempt to reverse this trend of resegregation and help our country fulfill the promise of Brown? I think it's true that educators alone can't put an end to racial segregation in schools. It's going to take a village, but educators play an important role in a number of ways, advocating for diversity and inclusive education in your school or your school district.

(32:06):

There are NEA members across the country who participate in state and local coalitions that seek to end policies and practices that have a negative impact on things like school funding and other educational resources. I would encourage listeners to look for opportunities to join up with these coalitions. Listeners could also investigate opportunities to collaborate with housing officials, right? There are lots of housing rights advocates and other officials in the housing space who are working to reduce racially segregated neighborhoods and communities. And I think it important for us to look at that not on its own, but as a way of achieving true integration of public schools. The more diverse our neighborhoods are, the more diverse our schools necessarily will be. And then I do have a few book recommendations for folks interested in learning more about the history of Brown, its impact or some of the other movements that have undermined the Promise of Brown. Book recommendations include Schoolhouse Burning by Derek Black, Engines of Liberty by David Cole and The Lie That Binds by Ellie Langford

Natieka (33:22):

Thank you so much for joining us today, Danielle. I know I learned a lot and I hope that our listeners have too.

Danielle (33:28):

Thank you so much for having me. It's such an important case, and I hope that our conversation helps remind people that the success of our schools and thus our democracy, really depends on all of us working together to fulfill the promise of Brown.

Natieka (33:44):

Thanks for listening. Make sure you subscribe so you don't miss a single episode of School Me. And take a minute to rate the show and leave a review. It really helps us out and it makes it easier for more educators to find us. For more tips to help you bring the best to your students, text Pod, that's P-O-D to 48744.

References

Join Our Movement