Bargaining for the Common Good

How to use this toolkit

In this resource guide, you will learn more about what makes a Bargaining for the Common Good campaign, along with tools and resources that your local can use to work with partners in your area to run a BCG campaign.

Foreword

Foreword

Since the 17th Century, our nation’s system of public education has been the undisputed foundation of an inclusive democracy, economy, and society. Public school classrooms are where our students first learn how democratic systems of government work, and where they develop an understanding of the principles and practices that will allow them to participate in the operation of the U.S. government.

Unfortunately, when they should be working to strengthen our democracy, some far-right politicians, policymakers and pundits are actively working to dismantle it. Their weapon? Escalated attacks against public education. From attempting to whitewash the nation’s history to eliminating the contributions and lived experiences of Black people and communities of color, to maligning and marginalizing LGBTQ+ students and educators, these attacks are only intended to fulfill the self-serving desires of the attackers and their wealthy donors.

Their efforts are rooted in the fertile ground of this sad truth: Inequity is sewn into every social system in our nation. These inequities make their presence known at every schoolhouse door, and in every other element of far too many communities.

With 3 million members, NEA is the nation’s largest labor union. As education professionals devoted to ensuring that the nation’s 50 million public school students receive the support, access, and opportunities they all need and deserve, we have not—and we will never—allow these unfounded and harmful attacks to go unanswered. We will continue to follow the North Star of our shared vision: to unite not just our members, but the nation to reclaim public education as a common good, as the foundation of our democracy, and then transform it into something it was never designed to be—a racially and socially just and equitable system that prepares every student, every one, to succeed in this diverse and interdependent world.

This Bargaining for the Common Good Racial Justice Guide represents a critical step toward the achievement of that vision.

The principles of Bargaining for the Common Good (BCG) are fastened to the belief that just as inequity is woven through the fabric of many communities, the collective bargaining process must have woven through it the unique needs and aspirations of the community that encircles the educators and students whose needs are represented at the bargaining table.

In addition to examples of how NEA state affiliates have bargained for the common good in schools and communities nationwide, this guide contains a roadmap for creating campaigns built from intentional, longterm partnerships between unions and community organizations. It also provides information about how those relationships can help to facilitate bargaining proposals designed to end the systemic patterns of racial inequity and injustice that hamper the progress of far too many students, educators, and public schools.

As parents, educators, and communities, we have a shared responsibility to ensure that every student—Black, White, Brown, Indigenous, or AAPI; students from underserved neighborhoods, LGBTQ+ students, and students who are disabled—all of our students—have the joy, justice and excellence they all need and deserve. Through bargaining for the common good, NEA is transforming that desire into a reality for students, educators, and communities across our nation.

Introduction to Racial Justice Centered Education

National Education Association (NEA) locals across the country are at the forefront of moving strategic demands grounded in racial justice that dismantle historical and pervasive racist structures in education. Locals are building with parents, students, and community partners to fight for a system where all students can thrive no matter their race, gender, or immigration status.

But for years, corporate actors and political players have stood in the way by defunding public schools and privatizing education, disproportionately impacting communities of color and low-income neighborhoods, implementing hurtful discipline policies that predominantly target students of color, and more recently censuring teachings about racial justice and the histories of Native People, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Black, Latino/ a/x, Middle Eastern and North African populations.

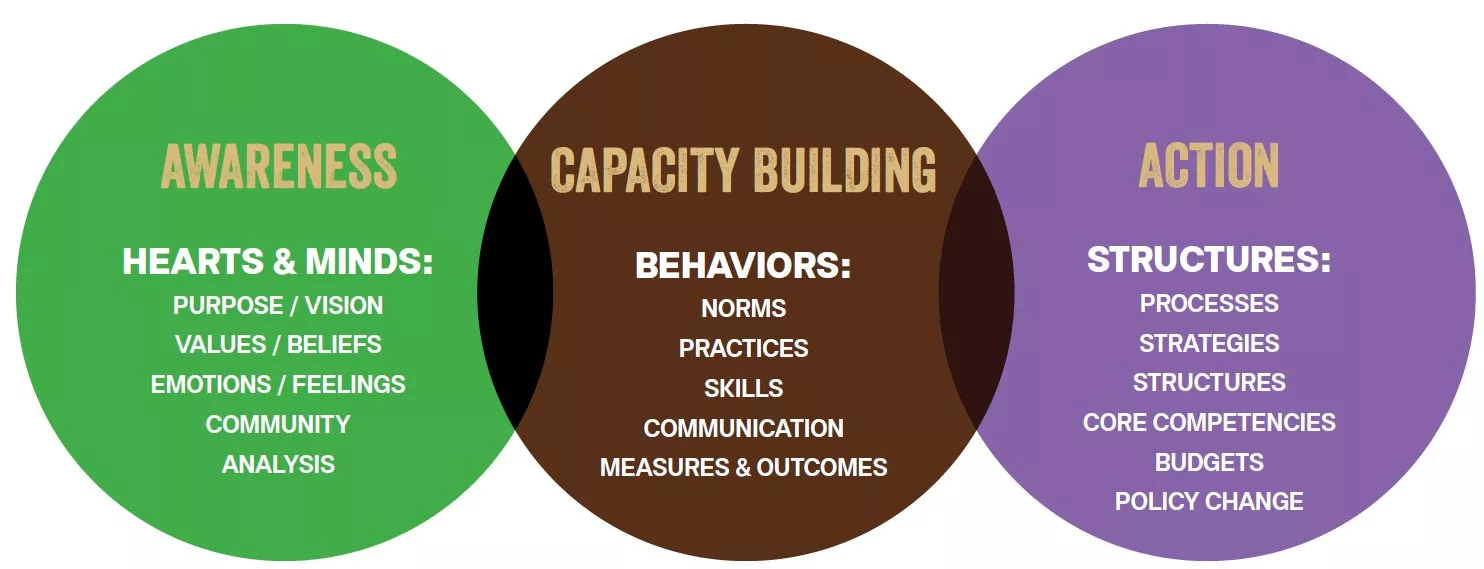

We must unite to take on these challenges. Union members are recognizing their dual roles as both workers and key leaders in their communities. In a changing and stratified economy, we are expanding collective bargaining, policy fights, and corporate campaigns to address the challenges we face as workers, neighbors, and families. Labor and community organizations are collaborating to advance unified demands that are relevant to both workers and the broader community. This way of coming together is called Bargaining for the Common Good (BCG).

In 2022 and 2023, we saw the power and energy of BCG in Oakland, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, and in growing numbers of states. These campaigns brought community members to the bargaining table with unions and thousands into the streets to take on corporate power and fight for the schools, housing, and cities we all deserve.

How are unions and community groups Bargaining for the Common Good?

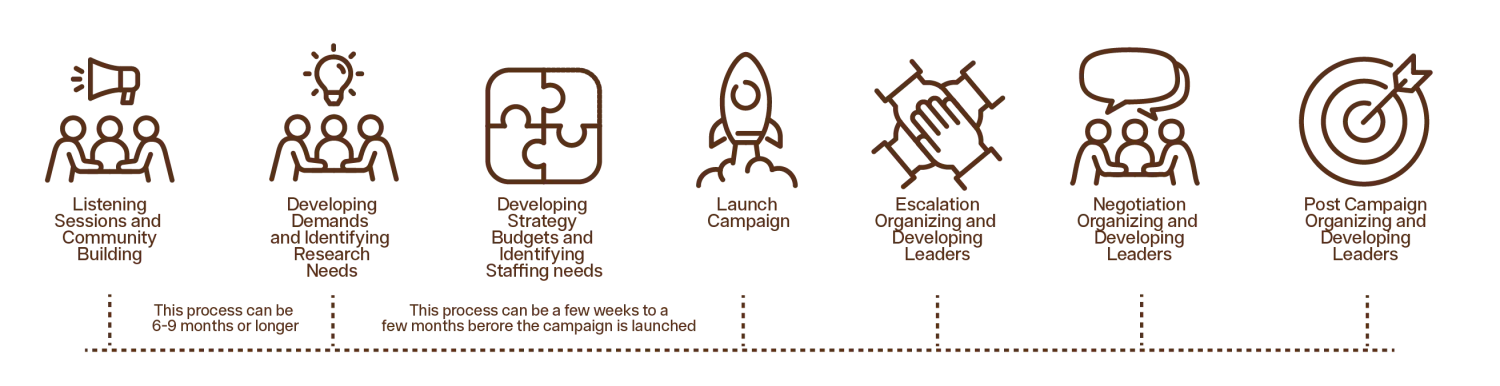

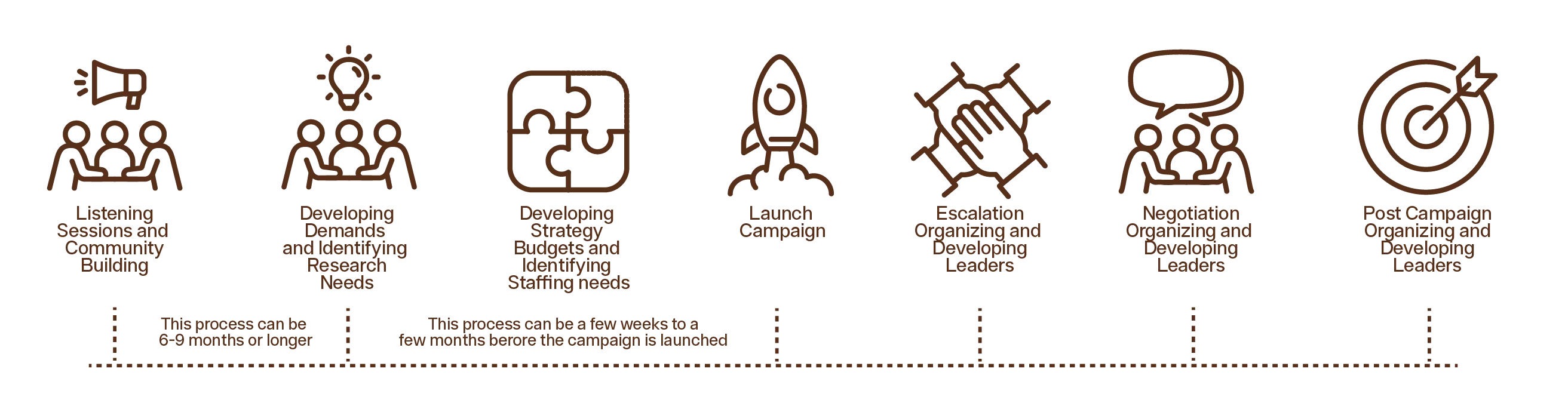

At the center of BCG campaigns are intentional, long-term alignments between unions and community organizations advancing racial justice demands. Connecting at all levels starting with membership, they build strong, lasting partnerships based on trust and a shared analysis of the systemic problems we are confronting and the solutions necessary to transform our communities. BCG campaigns are centered around joint community-labor planning that brings diverse partners to the table in union bargaining, policy fights, and corporate campaigns that build power and address the crises we all face. BCG work centers racial justice because we must collectively confront structural racism to create a powerful, unified movement.

Building strong, sustainable relationships is not easy. Effective BCG campaigns require unions to use the bargaining process as a tool to engage members in their dual identities as workers and community members. Community organizations must also educate its members about unions and how they can bargain together. Both groups must work to overcome any historic animosity or mistrust to develop a shared framework, from membership to leadership, that sees corporations and the wealthy elite as the perpetrators of injustice in our communities and workplaces.

In this resource guide, you will learn more about what makes a Bargaining for the Common Good campaign, along with tools and resources that your local can use to work with partners in your area to run a BCG campaign.