People from Asian and Pacific Island nations have been trading and settling in North America since the mid-1700s. Filipino traders were the first-known settlers from the Pacific Islands to make their home in Louisiana in the 1760s. By the mid-1800s, large numbers of Chinese laborers working on the trans-continental railroad and prospectors hoping to discover gold immigrated to the United States settling mostly in the West.

As the number of Chinese immigrants grew, so did xenophobic fears and policies from White Americans. For example, the ruling in People v. Hall in 1854 prohibited Asian Americans from testifying against White people. The 1862 Anti-Coolie Act “imposed a tax on Asian Americans who attempted to work in . . . factories” as a way to limit competition with White workers. Anti-Asian sentiments sometimes turned violent. In 1871, nearly 20 Chinese were lynched in Los Angeles. In 1885, Chinese-American miners were attacked by White miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming—28 people were killed and approximately 500 Chinese-Americans were driven from their homes. The following year, a riot in Seattle violently forced all Chinese-Americans to leave the city. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have had a long and continued struggle for civil and economic rights in the United States.

Within an economics or financial literacy class, the following historical examples provide context to help students understand economic issues that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders face today:

Notable Events

Naturalization Act of 1870

The Page Act of 1875

Chinese Exclusion Act

Tape v. Hurley

Yick Wo v. Hopkins

United States v. Wong Kim Ark

Alien Land Law

Immigration Act of 1917

Japanese Internment, Executive Order 9066

Repeal of Chinese Exclusion Act

Korematsu v. United States

Immigration and Nationality (McCarran-Walter) Act

Delano Grape Strike

Immigration and Nationality (Hart-Celler) Act of 1965

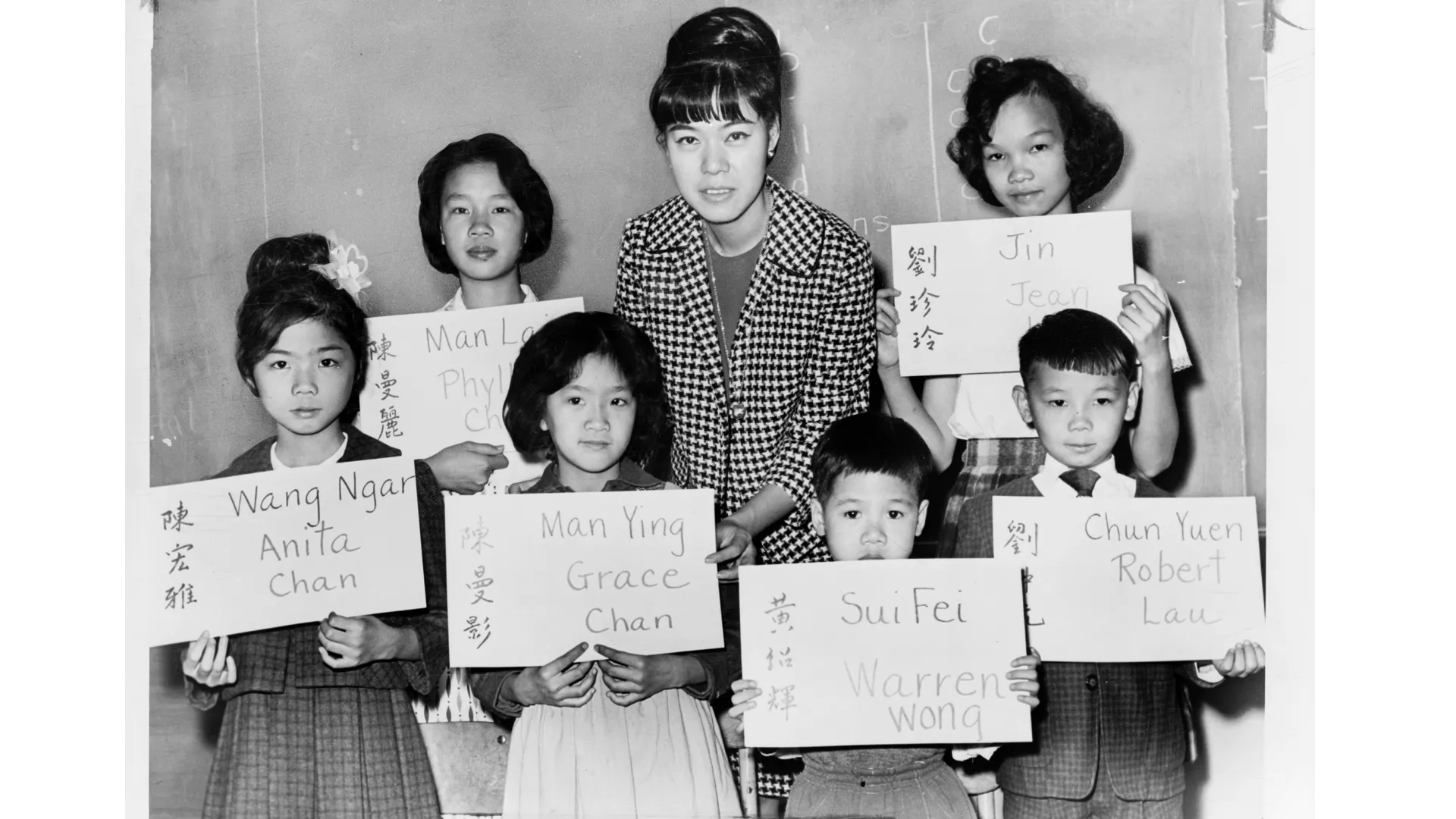

Lau v. Nichols

Equal Credit Opportunity Act

Are you an affiliate?