Guidance on Immigration Issues

Immigration and the demonizing of immigrants was central to President Trump’s 2024 election campaign and since his re-election, he and his staff have consistently signaled an intent to engage not only in aggressive immigration enforcement but also to reshape the nation’s immigration laws starting on January 20, 2025, the day he officially takes office. The proposals include promises to carry out the largest deportation program in American history and attempting to end birthright citizenship.

Educators, students, and families are understandably concerned about the safety of their families and communities. Unauthorized immigrants live in 6.3 million households that include more than 22 million people, this includes 4.4 million U.S.-born children who live with an unauthorized immigrant parent. Jeffrey S. Passel and Jens Manuel Krogstad, What we know about unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S., Pew Research Center (July 22, 2024), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/07/22/what-we-know-about-unauthorized-immigrants-living-in-the-us/. Go to reference If implemented as promised, Trump’s policies will lead to fear and upheaval, mass panic in immigrant communities, and will predictably harm school environments including by causing increased absences, decreased student achievement, and parental disengagement. U.S. Citizen Children Impacted by Immigration Enforcement, American Immigration Council (June 24, 2021), available at https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/us-citizen-children-impacted-immigration-enforcement. Go to reference

While many of Trump’s proposed immigration actions will face legal challenges, it is imperative for our leaders and members to be aware and prepared regarding the impact that immigration issues can have on schools and our communities. To that end, the following guidance lays out information regarding immigration and schools, including information around enrollment issues, Plyler v. Doe, and Safe Zones resolutions, how educators can safely engage in immigration advocacy, a FAQ around mass raids, a Know Your Rights guide around immigration enforcement, and an update on the DACA program.

NEA strongly encourages schools and school districts to adopt a Safe Zones policy that outlines what educators, and staff should do if ICE attempts to engage in immigration enforcement at schools. Hundreds of school districts around the country already have adopted a Safe Zones policy. The appendix at the end contains a model Safe Zones resolution, a model district policy and an FAQ on such policies for your use (Appendix A). If your school district has not yet adopted such a policy, we encourage you to take proactive action to ensure your schools are safe for all students.

This guidance and all attachments may be shared widely with educators, member leaders, and activists.

Contents

Immigration & Schools 101

Immigration Enforcement at Schools — The Importance of Safe Zone Policies

How Educators Can Safely Engage in Immigration Advocacy

Mass Raids FAQ

Know Your Rights: Immigration Enforcement

DACA Update

Sample Safe Zone Resolution and Model Policy

- 1 Jeffrey S. Passel and Jens Manuel Krogstad, What we know about unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S., Pew Research Center (July 22, 2024), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/07/22/what-we-know-about-unauthorized-immigrants-living-in-the-us/.

- 2 U.S. Citizen Children Impacted by Immigration Enforcement, American Immigration Council (June 24, 2021), available at https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/us-citizen-children-impacted-immigration-enforcement.

Immigration & Schools 101

All students have a right to enroll in public school, regardless of their immigration status.

- Under the U.S. Constitution, public schools must teach all students free of charge, regardless of whether they are undocumented.

- States cannot withhold state funding for K-12 education because undocumented students are enrolled, and school districts cannot deny enrollment based on immigration status.

- Sometimes called a “Plyler right,” the understanding that undocumented students may not be denied access to public education was first recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in its decision in Plyler v. Doe (1982).

Students have the right to attend school without having to present a green card, visa, social security number, or any other proof of citizenship.

- Schools should not inquire about students’ or their parents’ immigration status.

- Schools cannot deny enrollment to students because they provide a birth certificate from another country.

- Inquiring about immigration status or citizenship could violate Plyler rights by chilling undocumented students from attending schools.

Schools can require proof of residency in the appropriate school or district boundary.

- A state or district may establish bona fide residency requirements and thus might require that all prospective students show some proof of residency.

- Districts must permit parents to establish residency by providing a variety of documents as proof of residency and cannot require documents that would bar or chill undocumented students from attending.

- Such documents include: a telephone or utility bill, mortgage or lease document, parent affidavit, rent payment receipts, a copy of a money order made for payment of rent, or a letter from one of the parent’s employers. Schools cannot apply different residency requirements to immigrant students than they do to others.

- Homeless students, as defined by the Federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 11301 et seq., must not be required to furnish proof of residency within the district under any circumstance. Homeless children and youth have a federal legal right to enroll in school, even if their families cannot produce the documents establishing residency.

Schools can require proof of age for enrollment.

- Schools can use birth certificates to establish a student’s age but cannot do so in a way that unlawfully bars or prevents an undocumented student, a student whose parents are undocumented, or a homeless student from enrolling in and attending school.

- Schools should inform parents that alternatives to birth certificates are allowed, and allow alternative documentation of age such as a religious, hospital, or physician’s certificate showing date of birth; an entry in a family bible; an adoption record; an affidavit from a parent; a foreign birth certificate; previously verified school records; or any other documents permitted by law. Foreign-born students must not be barred from attending school.

Immigration Enforcement at Schools — The Importance of Safe Zone Policies

Since 2011, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has listed schools as “sensitive locations” where Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests, interviews, or searches should not take place absent unusual circumstances. In 2021, the Biden administration issued a new policy expanding the areas protected from enforcement beyond K-12 schools to pre-K through post-secondary schools, and places where children gather such as playgrounds, recreation centers, bus stops, childcare centers, and group homes for children.

- Trump did not rescind the “sensitive locations” guidance during his first administration, but immigration enforcement occurred near schools and school bus stops, including when ICE officers detained a parent in Los Angeles as he left school after dropping off one of his children. Such enforcement would not be permitted under the expanded Biden “protected areas” guidance.

- Project 2025 calls for rescinding the “protected areas” guidance and it remains to be seen whether the Trump Administration will withdraw this guidance.

Given the uncertainty about whether schools might be targeted, it is important to put protections in place at the local level that limit immigration enforcement at schools. Countless school districts around the country have already passed Safe Zones resolutions to do so. Such resolutions:

- Make clear that your school district is a welcoming place for all students, prohibit the collection of student immigration information and establish procedures for responding to immigration enforcement.

- You need to understand that a Safe Zone resolution does not provide immunity should you decline to obey directives from law enforcement. Rather, it provides steps that you should request that law enforcement follow. If law enforcement refuses to cooperate, that becomes a matter for district legal counsel and courts to determine. You should not put yourself or those around you at risk to enforce the requirements.

- Educators should never physically interfere with or obstruct an immigration officer in the performance of his or her duties as this could escalate the situation and could endanger both the educator and students.

If your school district has not yet adopted a Safe Zones resolution or other policy for all school staff to follow if immigration officers show up at school, the following information describes what educators should do.

- If immigration officers attempt to enter a school’s campus, educators should direct ICE/CBP agents to the school district Superintendent. The Superintendent should request to see written legal authorization and verify the identity of the agents. It is important for the Superintendent to review, with legal counsel, what the immigration officer provides as such legal authorization. There is a distinction between an ICE administrative warrant and a traditional federal court warrant. School districts may respond differently depending on the type of warrant.

- An ICE administrative “warrant” is the most typical type of “warrant” used by immigration officers. It authorizes an immigration officer to arrest a person suspected of violating immigration laws. It is not a warrant within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution because an ICE warrant is not supported by a showing of probable cause of a criminal offense and is not issued by a court judge or magistrate.

- An ICE warrant does not grant an immigration officer any special power to compel school officials to cooperate and is not a “court order” that would, under FERPA, allow a school to disclose educational records without parent or guardian consent.

- A federal or state court warrant is issued by a federal or state court judge. A school official should act in accordance with district policy when presented with a federal or state court warrant.

- An administrative subpoena is a document that requests production of documents or other evidence and is issued by an immigration officer. School districts do not need to immediately comply with the ICE administrative subpoena. If an immigration officer arrives with an administrative subpoena, the school district may decline to produce the information sought and may choose to challenge the administrative subpoena before a judge.

Project 2025 proposes requiring public schools to charge tuition to certain immigrant children as a way of setting up a legal challenge to overturn Plyler v. Doe. Plyler still remains the law of the land and public schools cannot deny undocumented students access to public education including by charging tuition to immigrant students. To protect students and their Plyler rights, you can:

- Work to pass state or local laws or policies such as Safe Zone resolutions (see above) that prohibit K-12 schools from collecting student immigration information.

- Work with your State Attorney General and State Department of Education to issue guidance making clear that schools should not collect student immigration data.

- Work with your State Attorney General and State Department of Education to issue guidance buttressing the right of all students to attend public school, regardless of immigration status, pursuant to Plyler v. Doe, your state constitution, and any applicable state laws.

- Make sure your school district does not collect immigration status in any educational records.

- If your school district begins collecting student immigration information or attempts to charge tuition to immigrant students, inform your state affiliate and NEA.

Under federal law, schools cannot turn over personally identifiable student records to police, federal agents, or immigration officials without the written consent of a parent or guardian, unless the information is requested through a subpoena or court order such as a judicial warrant.

- Schools can disclose students’ “directory information” without the family’s consent unless the school district is notified that the family has “opted out” from such sharing.

- Make sure that your school district does not include place of birth in directory information. If it does, advocate to end the practice of collecting place of birth information and decline to provide it for your children.

- Inform parents of their right to opt out of the directory information.

Remember that both federal and state and in many places local law protects students from discrimination based on race, religion, or national origin. This means that:

- Students cannot be discriminated against because of their birthplace, ancestry, culture or language.

- Students have the right to be free from bullying and harassment based on their race, religion, or national origin, and have the right to learn in an environment free from hateful symbols and derogatory comments.

- School officials have a legal duty to address hateful rhetoric and behavior.

- Schools may not retaliate against anyone – staff or students – who make complaints about racial, religious, or national origin harassment.

How Educators Can Safely Engage in Immigration Advocacy

Here are some legal parameters for educators to consider in safely and effectively advocating for immigrant students’ rights. A more in-depth discussion around educator advocacy rights at school and outside of school can be found in NEA’s Educator Rights Guidance.

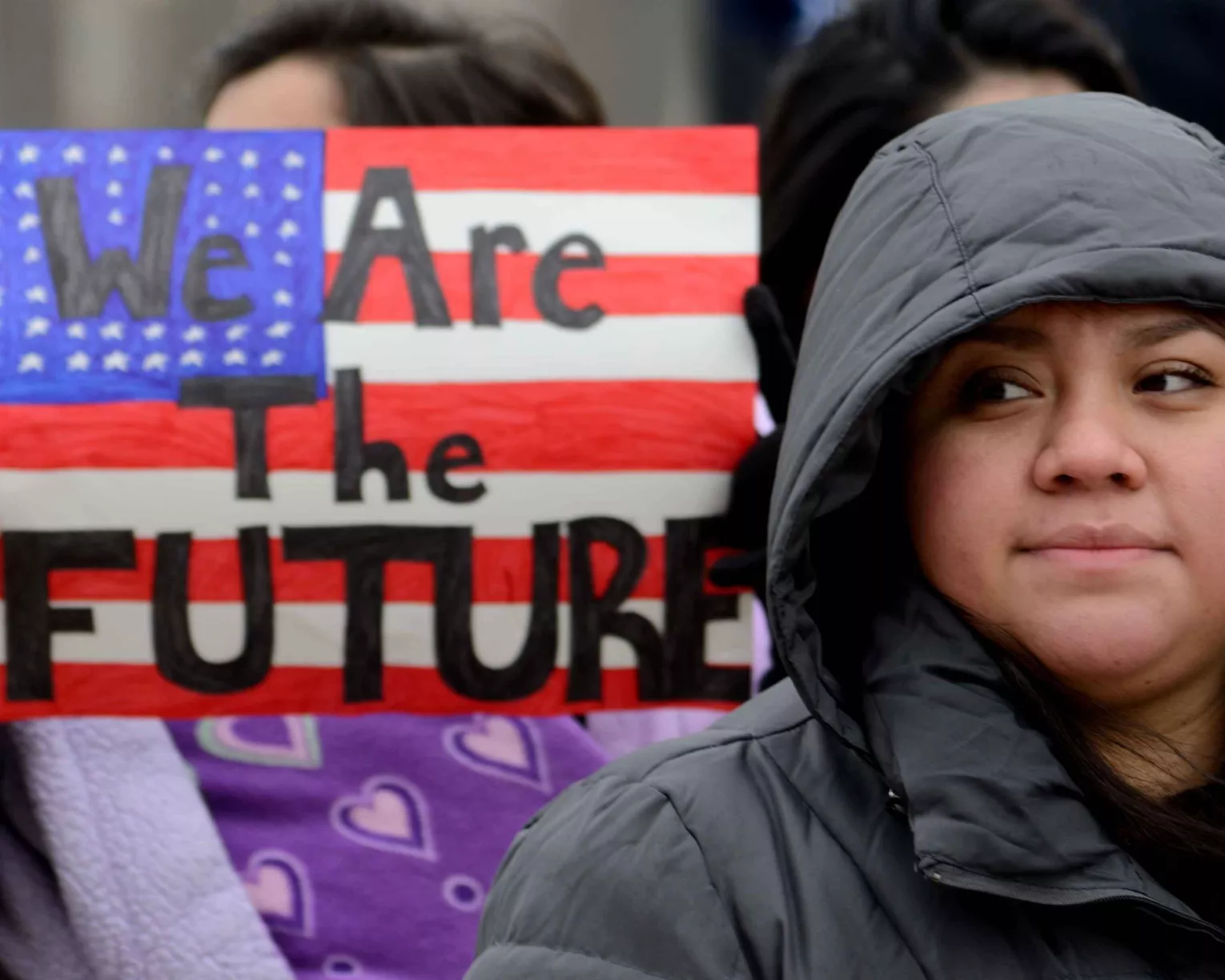

1. Your Protections Are Strongest When You Engage in Activism Outside of Work.

The First Amendment provides legal protection to educators when they are speaking as “citizens”— i.e., outside of their role as district employees. Educators can engage in off-the-clock political and community action to advocate for immigrants and immigrant communities. Educators can, among other things, march, sign petitions, write letters, post statements of support on social media, and call and lobby their federal, state, and local legislators. They can work with NEA and our affiliates, as well as other advocacy groups, to advocate for change such as encouraging their school districts to pass Safe Zone resolutions.

Educators are most protected when they engage in political discussions or activism outside of work, provided it does not cause disruption at the school. If the activity creates a disruption to the educational environment, an educator may be disciplined. Pickering v. Bd. Of Educ., 391 U.S. 563 (1968); Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138 (1983). Go to reference Even speech on social media and private blogs may be unprotected if it concerns the educator’s official duties. Rubino v. City of New York, 950 N.Y.S. 2d 494 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2012), aff’s, 106 A.D. 439, 965 N.Y.S. 2d 47 (2013). Go to reference For that reason, educators should focus such activity on advocacy for immigrant students and not disparage or insult students, parents, or co-workers. Richerson v. Beckon, 337 Fed. Appx. 637 (9th Cir. 2009). Go to reference

2. Protections That Apply to Your Speech at Work are More Limited.

Generally speaking, the First Amendment will not protect you from discipline based on statements made in class, Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006); Mayer v. Monroe Cty. Cmty. Sch. Corp., 474 F.3d 477 (7th Cir 2007); Brown v. Chicago Bd. of Educ., 824 F.3d 713 (7th Cir. 2016). Go to reference or to students during your usual work hours but outside of class. See Johnson v. Poway Unified Sch. Dist., 658 F.3d 954 (9th Cir. 2011). Go to reference Tenured teachers are provided due process and should be protected when engaged in classroom discussions about immigration that are both age-appropriate and relevant to the coursework. In addition, some collective bargaining agreements may contain explicit protections for academic freedom, which may protect educators who discuss these issues in a manner that is both age-appropriate and relevant to the curriculum. See Nalichowski v. Capshaw, No. CIV. 95-5577, 1996 WL 548143, at *2 3 (E.D. Pa. Sept. 20, 1996) (holding that violations of a collective-bargaining agreement containing an academic freedom provision were grieveable); Charlotte Garden, Teaching for America: Unions and Academic Freedom, 43 U. TOL. L. REV. 563, 580-82 (2012). Go to reference

Still, tenure protections and academic freedom are not absolute, and teachers risk discipline for classroom discussions that administrators consider too controversial, not age appropriate, or too great a departure from established curricula. Hollis v. Fayetteville Sch. Dist. No. 1, 473 S.W.3d 45 (Ark. App. 2015); Freshwater v. Mt. Vernon City Sch. Dist., 1 N.E.3d 335 (Ohio 2013). Go to reference School districts may also have policies restricting educators’ in-school activism and use of handouts. Educators should seek the school administration’s approval of advocacy materials that they plan to distribute to students and their families.

3. Engaging in Protests at School Can Be Prohibited.

Educators have even more limited protection against discipline for activism at school including by way of encouraging students to engage in protests that involve civil disobedience or school disruption. Because educators are acting within the scope of their job duties while at school, the First Amendment may not apply when educators wear political buttons or other activist symbols, or urge students to participate in protests. Weingarten v. Bd. of Educ., 680 F. Supp.2d 595 (S.D.N.Y. 2010); Birdwell v. Hazelwood Sch. Dist., 491 F.2d 490 (8th Cir. 1974). Go to reference Likewise, because many school districts have policies that explicitly prohibit employees from engaging in political activity during work time, violations of such a policy could qualify as insubordination that justifies discipline, even of a tenured educator. Ca. Teachers Ass’n v. Governing Bd. of San Diego Unif. Sch. Dist., 53 Cal. Rptr. 2d 474 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996). Go to reference Similarly, students have a right to voice their opinions and engage in certain forms of school protest, but they can be disciplined if such activities become disruptive or disorderly. Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969). Go to reference

4. What can faculty teaching in public higher education institutions do to advocate for immigrants?

Like public K-12 educators, faculty members at public colleges and universities can engage in off-the-clock political and community action. In addition, principles of academic freedom under the First Amendment give higher education faculty speech protections while engaged in core academic functions such as teaching and scholarship. Combined with widespread policies on academic freedom in faculty handbooks, collective bargaining agreements, and faculty contracts, faculty speech in the higher education workplace receives more protection than in the K-12 setting. However, faculty are not immune from discipline based upon their speech, and speech may lose First Amendment or institutional policy protection if it is not related to the academic subject or is unduly disruptive.

5. Congress Has Criminalized the Harboring of Undocumented Immigrants.

If you provide shelter to students or their families knowing that they are undocumented, you may face criminal consequences. Federal law prohibits a person from concealing, harboring, or shielding from detection someone who that person knows—or should know— to be undocumented. 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(iii) (2005). Go to reference This crime is referred to as “harboring” undocumented immigrants. A conviction can result in up to five years in prison for each immigrant sheltered. 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(B)(ii) (2005). Go to reference

Harboring requires that the person charged must have intended both (a) to substantially help an undocumented person remain in the United States (such as by providing shelter, transportation, money, or other material assistance) and (b) to help the individual avoid detection by immigration authorities. United States v. Vargas-Cordon, 733 F.3d 366, 382 (2d Cir. 2013); United States v. Costello, 666 F.3d 1040, 1047 (7th Cir. 2012); United States v. You, 382 F.3d 958, 966 (9th Cir. 2004). Go to reference When the act of sheltering an undocumented person is done publicly—i.e., a church offering sanctuary to immigrants in danger of deportation—such actions are grounds to infer an intent to evade immigration authorities and would thus support a charge of criminal harboring. Costello, 666 F.3d at 1047; United States v. McClellan, 794 F.3d 743, 749 (7th Cir. 2015). Go to reference Merely providing a place to stay for an undocumented person, however, should not constitute a criminal offense so long as the person providing shelter does not intend to help the undocumented individual evade immigration authorities. See, e.g., Costello, 666 F.3d at 1046 (declining to extend the prohibitions of § 1324 to prosecute a woman whose undocumented boyfriend lived in her house). Go to reference

Download this section as a PDF

- 3 Pickering v. Bd. Of Educ., 391 U.S. 563 (1968); Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138 (1983).

- 4 Rubino v. City of New York, 950 N.Y.S. 2d 494 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2012), aff’s, 106 A.D. 439, 965 N.Y.S. 2d 47 (2013).

- 5 Richerson v. Beckon, 337 Fed. Appx. 637 (9th Cir. 2009).

- 6 Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006); Mayer v. Monroe Cty. Cmty. Sch. Corp., 474 F.3d 477 (7th Cir 2007); Brown v. Chicago Bd. of Educ., 824 F.3d 713 (7th Cir. 2016).

- 7 See Johnson v. Poway Unified Sch. Dist., 658 F.3d 954 (9th Cir. 2011).

- 8 See Nalichowski v. Capshaw, No. CIV. 95-5577, 1996 WL 548143, at *2 3 (E.D. Pa. Sept. 20, 1996) (holding that violations of a collective-bargaining agreement containing an academic freedom provision were grieveable); Charlotte Garden, Teaching for America: Unions and Academic Freedom, 43 U. TOL. L. REV. 563, 580-82 (2012).

- 9 Hollis v. Fayetteville Sch. Dist. No. 1, 473 S.W.3d 45 (Ark. App. 2015); Freshwater v. Mt. Vernon City Sch. Dist., 1 N.E.3d 335 (Ohio 2013).

- 10 Weingarten v. Bd. of Educ., 680 F. Supp.2d 595 (S.D.N.Y. 2010); Birdwell v. Hazelwood Sch. Dist., 491 F.2d 490 (8th Cir. 1974).

- 11 Ca. Teachers Ass’n v. Governing Bd. of San Diego Unif. Sch. Dist., 53 Cal. Rptr. 2d 474 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996).

- 12 Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

- 13 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(iii) (2005).

- 14 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(B)(ii) (2005).

- 15 United States v. Vargas-Cordon, 733 F.3d 366, 382 (2d Cir. 2013); United States v. Costello, 666 F.3d 1040, 1047 (7th Cir. 2012); United States v. You, 382 F.3d 958, 966 (9th Cir. 2004).

- 16 Costello, 666 F.3d at 1047; United States v. McClellan, 794 F.3d 743, 749 (7th Cir. 2015).

- 17 See, e.g., Costello, 666 F.3d at 1046 (declining to extend the prohibitions of § 1324 to prosecute a woman whose undocumented boyfriend lived in her house).

Mass Raids FAQ

Trump’s 2024 Presidential campaign was based on false, inflammatory rhetoric about immigrants. He has pledged to institute a program of mass deportation of millions of people, beginning on day one of his administration. Below are some frequently asked questions about what mass deportations and raids could mean and what educators can do to prepare for the possibility of mass raids.

- Where might “mass raids” take place, geographically?

- In the past, ICE has conducted raids all over the country – not just in places close to the border. Some of the largest raids have been in interior states like Tennessee.

- We can anticipate that more raids may take place in states and localities where law enforcement has agreed to cooperate with ICE. A list of locations with 287(g) agreements (for cooperation) is available here: https://www.ice.gov/identify-and-arrest/287g

- Who is most likely to be targeted for deportation?

- The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has historically questioned a wide range of workers during an audit or raid, regardless of the initial scope of their investigation. We expect similar tactics to continue and even expand.

- Some people believe that the Trump administration plans to deport only undocumented people who have committed serious crimes. But some Trump supporters regard all undocumented people as criminals – on the theory that they entered the United States illegally. In addition when mass raids occur, those with legal status in the U.S. may accidentally be swept up by immigration enforcement. Therefore, it is important for everyone to be vigilant.

- The first Trump administration prioritized the following individuals for removal, but it is unclear whether similar priorities will guide the second Trump administration. Individuals who had been:

- Convicted of any criminal offense;

- Charged with any criminal offense, where such charge has not been resolved;

- Or who have committed acts that constitute a chargeable criminal offense;

- Have engaged in fraud or willful misrepresentation in connection with any official matter or application before a governmental agency;

- Have abused any program related to receipt of public benefits;

- Are subject to a final order of removal, but who have not complied with their legal obligation to depart the United States; or

- In the judgment of an immigration officer, otherwise pose a risk to public safety or national security.

- Is someone’s family or home at risk during an ICE workplace operation or raid?

- During a workplace raid or operation, ICE also may visit workers’ homes, particularly of workers whose records are found at the company.

- If ICE agents visit a worker’s home, families are under no obligation to answer questions or even open the door unless the agents have a warrant signed by a federal or state court judge.

- ICE is known to routinely question people who are present during operations—even if they have no relation to the investigation. If ICE can identify family members or other household members whom they deem a priority for deportation, those individuals also could be detained and taken into immigration custody, sometimes referred to as “collateral arrests.”

- What might occur during a mass raid?

- Immigration raids can happen at any given time, but they rely heavily on an element of surprise.

- Historically, raids most frequently have taken place at the individual’s workplace or in or near their home.

- Raids often take place during predawn or early morning hours.

- ICE officers often appear in large numbers, may be visibly armed and may not be easily identifiable as ICE agents.

- Other common features of these raids: an absence of a warrant from a state or federal court, and an agent giving false or misleading information to gain access to the home and to describe the nature and length of the arrest.

- Could raids take place at schools?

- Under current DHS policy, schools (including colleges, universities, and other institutions of learning) and other locations where children gather (such as daycares and playgrounds) are “protected areas,” (previously referred to as “sensitive locations”) generally protected from immigration enforcement.

- There have been calls to withdraw the “protected areas” policy.

- Even if the “protected areas” policy is withdrawn, it is unlikely there would be mass raids at schools due to the level of disruption that it would cause to all students and educators. But if the policy is withdrawn, we can expect increased immigration enforcement at or near schools.

- How can schools help families prepare for the possibility of mass raids?

- Partner with pro bono attorneys or immigrants’ rights groups to host “know your rights” workshops for families and students

- Distribute Red Cards to help people assert their rights and defend themselves if ICE agents come to their home.

- These cards are available in 16 different languages

- The “Know Your Rights” section below can be shared with families.

- Share “Know Your Rights” tutorial videos in seven languages.

- Distribute Red Cards to help people assert their rights and defend themselves if ICE agents come to their home.

- Provide information about community resources

- Compile a list of local nonprofit organizations that provide free legal support and other services to immigrants.

- Gather the information for foreign consulates in your area.

- Obtain the contact information for the local ICE detention center.

- Encourage families to download the Notifica app, which can distribute notice to emergency contacts in the event of a raid.

- Encourage families to create emergency plans and help them do so.

- A Family Preparedness Plan should include considerations such as

- Who will take care of children (and/or the elderly) if one or more parents are detained?

- Do you want to designate an official power of attorney?

- Who will have access to the assets of anyone detained?

- Do I know of any reliable immigration attorneys? If yes, keep their information close by.

- Families should gather children’s documents such as birth certificates, social security cards, medical records, and school records.

- Make sure adults know their alien registration number also referred to as their “A-number.”

- A Family Preparedness Plan should include considerations such as

- Partner with pro bono attorneys or immigrants’ rights groups to host “know your rights” workshops for families and students

- What plans can schools have in place to prepare for raids that affect families?

- Check frequently with families to ensure that contact information is up to date, since phone numbers and addresses could change multiple times during a school year.

- Affirmatively request that parents list one or two local friends or family members who could receive (“check out”) the child in the event of an ICE raid or other emergency.

- After a raid, sometimes only people who are not listed on the child’s school registration list may be available to pick them up.

- Have a list of potential interpreters at the ready. After a raid, expect to be overwhelmed by the need for Spanish speakers to respond to questions and serve those attempting to get students checked out to responsible adults. A shortage of interpreters may be especially acute in more rural areas.

- Reach out to universities in the area if there are any Spanish faculty/students who might be willing to interpret.

- Compile a list of community interpreter volunteers ahead of time.

- Set up a rapid-response network or become part of an existing one.

- This might include planning for text trees, phone trees, recruiting videographers and photographers, people to make banners, legal observers, etc. Make sure attorneys and communications-focused people are included as well.

- Create a network of friends, family, and neighbors to be ready to protest or take action if a raid happens.

- How can families find a loved one that is detained?

- You can search the Online Detainee Locator System using the person’s Alien Registration Number and country of origin or biographical information.

- If you cannot find a person using the online locator, call your local ICE office. For a directory of local ICE offices, visit www.ice.gov/contact/ero

- What can citizen bystanders do during an immigration raid?

- Report the raid

- United We Dream hotline: 1-844-363-1423.

- Text: 877877

- Record the raid using pictures and video if possible.

- Ahead of time, ensure that your device’s audio and video are on and set up to share to the cloud.

- Make sure to get the agents’ badge numbers and try to get their name and agency as well.

- Narrate the date, time, and location where the raid is occurring.

- Do not disclose the information of your loved ones or yourself to the agents. However, in some states you must give your name if asked.

- Important considerations for recording:

- ICE agents are armed law enforcement officials who are first and foremost concerned for their own safety. Before taking out a recording device, it is best to assess the situation and determine whether taking a video could escalate the situation and endanger anyone present.

- It is extremely important that if you choose to record, you must make it obvious that you are recording. Almost every state has laws against “secret” recordings. Do not cover up, hide or conceal your camera/phone.

- Your right to record law enforcement usually comes with the qualification that you must not “interfere” as they are carrying out their “duties.” This means you should stand several feet away from any law enforcement action taking place if you choose to record.

- If ICE warns you and asks you to step back while videoing/photographing, it is best to follow directions, as they may confiscate your camera.

- Report the raid

- What are an employer’s rights and responsibilities during a raid?

- ICE Arrival

- Employers should call their lawyer immediately when a raid begins.

- Examine any search warrant and send a copy to your lawyer. Ensure the warrant is:

- Signed by a federal or state court,

- Served within the permitted time frame,

- The search is within the scope of the warrant (the area to be searched and the items to be seized).

- The employer can accept the warrant but not consent to the search. If you do not consent to the search, the search will proceed but you can later challenge it if there are grounds to do so.

- Write down the name of the supervising ICE agent and the name of the U.S. Attorney assigned to the case.

- Executing the Raid

- Do not block or interfere with ICE activities or the agents. However, you do not have to give the agents access to non-public areas if they did not present a valid search warrant.

- If agents presented a valid search warrant and want access to locked facilities, unlock them.

- Object to a search outside the scope of the warrant. Do not engage in a debate or argument with the agent about the scope of the warrant. Simply present your objection to the agent and make note of it.

- Have at least one company representative follow each agent around the facility. The employee may take notes or videotape the officer. Note any items seized and ask if copies can be made before they are taken. If ICE does not agree, you can obtain copies later.

- Request reasonable accommodations as necessary. If agents insist on seizing something that is vital to your operation, explain why it is vital and ask for permission to photocopy it before the original is seized. Reasonable requests are usually granted.

- Protect privileged materials.

- If agents wish to examine documents designated as attorney-client privileged material (such as letters or memoranda to or from counsel), tell them they are privileged and request that attorney-client documents not be inspected by the agents until you are able to speak to your attorney.

- If agents insist on seizing such documents, you cannot prevent them from doing so. If such documents are seized, try to record in your notes exactly which documents were taken by the agents.

- Ask for a copy of the list of items seized during the search. The agents are required to provide this inventory to you.

- Employee Interactions with ICE

- You may inform employees that they may choose whether or not to talk with ICE, but do not direct them to refuse to speak to agents when questioned.

- Ask if your employees are free to leave. If they are not free to leave, they have a right to an attorney. Though you should not instruct your employees to refuse to speak to ICE, they also have the right to remain silent and do not need to answer any questions.

- Do not hide employees or assist them in leaving the premises.

- Do not provide false or misleading information, falsely deny the presence of named employees, or shred documents.

- Don’t forget the health and welfare of your employees. Enforcement actions can sometimes last for hours. If an employee requires medication or medical attention or if employees have children who need to be picked up from school, communicate these concerns to the ICE officers.

- Company representatives should not give any statements to ICE agents or allow themselves to be interrogated before consulting with an attorney.

- ICE Arrival

- What are some other immigration and refugee hotlines that may be of use?

- National Immigration Detention Hotline: 1-209-757-3733 (open Monday through Friday 12pm to 8pm PST) or for more information on the hotline you can also go to: https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/hotline

- United We Dream. To report a raid call 1-844-363-1423. Or send a text message to 877877. If possible, take photos and videos, and notes.

- National Korean American Service & Education Consortium (NAKASEC) hotline: 1-844-500-3222

- Tahirih’s Afghan Asylum Line 1-888-991-0852 Open Monday to Friday 10 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. EST.

- LGBTQ Immigrant Hotlines

- Immigration Equality – National LGBTQ Immigrant Rights Legal Emergency Help: 1-212-714-2904 (hotline open weekdays during daytime hours EST) or go to their website to fill out a contact form: www.immigrationequality.org/get-legal-help/#.WphaiRPwYWo

- For state and local hotlines for raids, detentions & deportations, please visit https://nnirr.org/education-resources/community-resources-legal-assistance-recursos-comunitarios-asistencia-legal/immigration-hotlines-lineas-directas-de-inmigracion/

- For more information about an individual’s rights during a raid, see the Know Your Rights: Immigration Enforcement section below.

Know Your Rights: Immigration Enforcement

Everyone who lives in the U.S. has legal rights, regardless of immigration status.

You have the right to remain silent. You may refuse to speak to immigration officers.

- Don’t answer any questions. You may also say that you want to remain silent.

- Don’t say anything about where you were born or how you entered the U.S.

- Anything you say can be used against you in removal proceedings. If you do decide to speak to officers, do not lie.

- Carry a rights card that says you want to remain silent and contact your attorney.

- If you chose to speak, do not lie.

- If you are in police custody or detention, do not discuss your immigration information with ANYONE other than your attorney.

Do not open your door.

- If officers are at your door, keep the door closed and ask if they are immigration agents or from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Ask the agents why they are there.

- It is safer to speak to ICE through the door.

- If the agents don’t speak your language, ask for an interpreter.

- ICE must have a warrant signed by a judge to be allowed to enter your home. They rarely have one.

- Do not open your door unless an ICE agent shows you a warrant signed by a judge.

- You can ask the ICE agent to hold the warrant against a window or slide it under the door.

- In order to enter your home, the warrant must be a valid arrest or search warrant signed by a judge. To be enough to enter your house, the warrant must contain the following:

- It must be issued by a court and signed by a judge. Look at the top and the signature line to see if it is a judicial warrant.

- It must name a person in your residence and/or areas to be searched at your address.

- In all other cases, keep the door closed and say, “I do not consent to your entry.”

- An administrative warrant of removal or deportation signed by DHS or ICE officials does not allow ICE to enter your home.

- If you open the door, officials will consider that you are giving them permission to enter. Once they are inside, an ICE officer will likely ask for documents of everyone inside.

- Even if immigration agents have a valid warrant that does not mean you have to answer their questions. If immigration agents are questioning you and you wish to remain silent, you should say aloud that you wish to remain silent or show the agents your Know Your Rights card.

- For more information on how to use your rights card, this is an illustrated and multilingual guide.

- If officers enter (with or without a valid warrant), say that you do not consent.

If you are approached by authorities in a public place/on the street:

- Do not run. Running could be used against you.

- Before saying anything (including your name) ask, “Am I free to go?”

- If yes, walk away slowly. If no, do not walk away.

- In some states, you must give your name.

- If you are searched, stay calm and say, “I do not consent to this search.”

If authorities pull you over in the car:

- Pull over, turn the car off and put your hands on the steering wheel.

- Follow all instructions, including providing license, registration, and insurance. Do not give false documents.

- If an officer searches your car, stay calm and say, “I do not consent to this search.”

If you are arrested or detained, do not physically resist or fight back. Do not lie or show false documents.

You have the right to speak to a lawyer.

- You can just say, “I need to speak to my attorney.”

- You may have your lawyer with you if ICE or other law enforcement questions you.

- If you are placed in jail/police custody or in an immigration detention center, request a phone call to your attorney.

Do not sign anything without speaking to a lawyer.

- You can refuse to sign any document. ICE may try to get you to sign away your right to see a lawyer or judge. Make sure you understand what a document actually says before you sign it.

- Do not rely on what ICE officers are telling you about what the document says.

- If you have a lawyer, you can ask for your lawyer to be present before signing any document. You always have the right to understand what you are signing.

Always carry with you any valid immigration documents you have.

- For example, a valid work permit, a DACA authorization, or green card.

- Do not carry false documents or papers from another country with you, like a foreign passport. They could be used against you in the deportation process.

Have an Emergency Plan.

- Memorize the phone number of a friend, family member, or attorney to call if you are arrested.

- Identify an attorney. Find out the name of a reliable immigration attorney ahead of time and keep their information with you at all times.

- Select someone to take care of your family, especially children and the elderly. If you fear that your deportation will leave your children without a guardian, create a family preparedness plan. This may mean consulting with an attorney to properly establish a guardian for your children, make sure your children and the guardian know about the plan, and that the guardian can access the resources needed to care for your children.

- Create a list of your medications and your family members’ medications.

- Prepare a safe place at home where you keep important papers and contact information such as birth certificates and immigration documents and make sure that the person you have selected to take care of your family knows where that place is.

If you need a lawyer:

- Nonprofit organizations that provide low-cost help can be found at immigrationlawhelp.org.

- The immigration courts have a list of lawyers and organizations that provide free legal services: justice.gov/eoir/list-pro-bono-legal-service-providers-map.

- At https://www.adminrelief.org there is a search engine that lists all legal services near your zip code.

- You can search for an immigration lawyer using the American Immigration Lawyers Association’s online directory, ailalawyer.com.

- The National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild also has an online find-a-lawyer tool: https://www.nationalimmigrationproject.org/find.html.

Report Raids

- If you are caught in a raid, do not run.

- If possible, take photos and videos of the raid or arrest. When you are safely able to do so, take detailed notes on what happened.

- Call United We Dream’s hotline to report a raid: 1-844-363-1423 or text 877877.

Additional Resources

-

The ICE detainee locator (https://locator.ice.gov/odls/#/search) can help people determine if their family member has been detained and where the family member is being held. In using the ICE detainee locator, it is helpful to know the family member’s date of birth and ‘A-Number’ (Alien Registration Number), if there is one. The ICE detainee locator is intended only for locating individuals who are already detained.

DACA Update

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) allows young immigrants who grew up in the U.S. to seek temporary protection from deportation and to have the ability to work. There are approximately 579,000 active DACA holders. Migration Policy Institute, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/shrinking-number-daca-participants. Go to reference The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals is currently reviewing the legality of the DACA program. Oral arguments occurred in October 2024 and we are currently awaiting a decision from the court, which could come at any time and almost certainly will be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. At present, current DACA recipients keep their deferred action status and work permits until they expire and current DACA recipients are able to renew their DACA permits.

Employers can ask for an updated DACA permit if the expiration date is approaching or there is some reason to believe the employee has become undocumented and may terminate an individual’s employment absent DACA or some other legally recognized immigration status. An employer should only ask you for your work authorization once they offer you a job, not before.

If you have never had DACA before, you may not submit an application for DACA now. Only people who now have or have previously had DACA can submit an application to renew their DACA.

DACA renewals continue to be accepted and processed and DACA recipients should continue to renew their permits. DACA recipients may qualify for another immigration benefit that could lead to permanent residence and not know it. Please consult with legal counsel to discuss potential options that may be available.

Download this section as a PDF

- 18 Migration Policy Institute, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/shrinking-number-daca-participants.

Appendix A: Sample Safe Zone Resolution and Model Policy

It is the right of every child, regardless of immigration status, to access a free public K-12 education.

When federal immigration authorities aggressively pursue enforcement activities on or around school property and transportation routes — whether by surveillance, interviews, demands for information, arrest, detention, or any other means — it harmfully disrupts the learning environment and significantly interferes with the ability of all students, including U.S. citizen students and immigrant students legally in the country, to access a free public K-12 education.

NEA has developed sample resolution and district policy that can be used as a template or guidance for local school districts to create their own Safe Zones resolutions. The language is closely tied to the Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe which is the foundational precedent that ensures access to K-12 education for all children regardless of immigration statust. The model resolution contains reassurances for students, procedures for law enforcement, and information and support for families and staff.

FAQ: Safe Zone School Board Resolutions

What can we do to address student fear about immigration enforcement under the new Administration?

Join with your local NEA association to lobby your local school board for a SAFE ZONE resolution. It contains reassurances for students, procedures for responding to law enforcement, and information and support for families and staff. Countless school districts across the country have already passed SAFE ZONE resolutions. These districts include large urban districts like Los Angeles, to small rural districts in Colorado and New Hampshire, and everywhere in between, such as Omaha, Nebraska, and Louisville, Kentucky.

What needs to take place in order for our district to become a SAFE ZONE?

Your school board can take up a proposed resolution like the one attached here at its next regularly scheduled meeting. Supply your school board with sample language and be sure to comply with the board’s meeting notice requirements. Through the board’s normal governance procedure, it can approve and sign a SAFE ZONE resolution, including a policy that would then take effect immediately.

Does a SAFE ZONE resolution require additional district expenditures, staff responsibilities, school hours, or other resources?

No, unless you wish to add support beyond NEA’s template, such as adding a counselor for extra support for immigrant students who are in crisis. The template SAFE ZONE resolution reaffirms and clarifies the constitutional right all students have, regardless of immigration status, to access a free public K-12 education. The district administration will need to take steps to ensure the resolution’s requirements are being fulfilled as outlined in the district policy attached to the NEA template SAFE ZONE board resolution, but it does not add new or different job duties or hours for educators.

Can I discuss immigration enforcement and student fears in my classroom?

Yes, if your school board passes a SAFE ZONE resolution that provides for such discussion, the discussion is age appropriate and mandatory curricular subjects are also covered in a timely way. The productivity of the learning environment improves when pressing concerns of students can be addressed. In the absence of a SAFE ZONE resolution, NEA recommends you follow existing district rules on classroom teaching.

Can I refuse directives from law enforcement?

No, a SAFE ZONE resolution does not provide immunity should you decline to obey directives from law enforcement. The resolution does provide steps you must request that law enforcement follow. If law enforcement refuses to cooperate, that becomes a matter for the district legal counsel and courts to determine. You are not expected to put yourself or those around you at risk to assert these rights.

Does the model SAFE ZONE resolution protect non-citizen students from the school-to-prison-to-deportation pipeline?

No, SAFE ZONE policies like the one attached here are aimed at protecting students’ rights at school but do not address disciplinary practices that criminalize misbehavior through the involvement of law enforcement. In the case of non-citizen youth, law enforcement actions can result in barriers to obtaining or maintaining legal

immigration status as well as possible detention and deportation. For information regarding the harmful immigration consequences for non-citizen youth of the school-to-prison pipeline, click here.

____________________ Board of Education

Resolution No. _____________

WHEREAS, it is the right of every child, regardless of immigration status, to access a free public K-12 education and the District welcomes and supports all students;

WHEREAS, the District has a responsibility to ensure that all students who reside within its boundaries, regardless of immigration status, can safely access a free public K-12 education;

WHEREAS, federal immigration law enforcement activities, on or around District property and transportation routes, whether by surveillance, interview, demand for information, arrest, detention, or any other means, harmfully disrupt the learning environment to which all students, regardless of immigration status, are entitled and significantly interfere with the ability of all students, including U.S. citizen students and students who hold other legal grounds for presence in the U.S., to access a free public K-12 education;

WHEREAS, through its policies and practices, the District has made a commitment to a quality education for all students, which includes a safe and stable learning environment, means of transportation to and from school sites, the preservation of classroom hours for educational instruction, and the requirement of school attendance;

WHEREAS, parents and students have expressed to the District fear and confusion about the continued physical and emotional safety of all students and the right to access a free public K-12 education through District schools and programs;

AND WHEREAS, educational personnel are often the primary sources of support, resources, and information to assist and support students and student learning, which includes their emotional health;

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED that the U.S. Immigrations Enforcement Office (ICE), state or local law enforcement agencies acting on behalf of ICE, or agents or officers for any federal, state, or local agency attempting to enforce federal immigration laws, are to follow District Policy ___, attached to and incorporated in this Resolution, to ensure the District meets its duty to provide all students, regardless of immigration status, access to a free public K-12 education;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the Board declares the District to be a Safe Zone for its students, meaning that the District is a place for students to learn, to thrive and to seek assistance, information, and support related to any immigration law enforcement that interferes with their learning experience;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the District shall, within 30 days of the date of this Resolution, create a Rapid Response Team to prepare in the event a minor child attending school in the District is deprived of adult care, supervision, or guardianship outside of school due to a federal law enforcement action, such as detention by ICE or a cooperating law enforcement agency;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, it continues to be the policy of the District not to allow any individual or organization to enter a school site if the educational setting would be disrupted by that visit; given the likelihood of substantial disruption posed by the presence of ICE or state or local law enforcement agencies acting for ICE, any request by ICE or other agencies to visit a school site should be presented to the Superintendent’s Office for review as to whether access to the site is permitted by law, a judicial warrant is required, or any other legal considerations apply; this review should be made expeditiously, but before any immigration law enforcement agent or officer appears at a school site;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, in its continued commitment to the protection of student privacy, the District shall review its record-keeping policies and practices to ensure that no data is being collected with respect to students’ immigration status or place of birth; and cease any such collection as it is irrelevant to the educational enterprise and potentially discriminatory;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, should ICE or other immigration law enforcement agents request any student information, the request should be referred to the Superintendent’s Office to ensure compliance with Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), student constitutional privacy, standards for a judicial warrant, and any other limitation on disclosure; this review should be conducted expeditiously, but before any production of information is made;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, the District shall post this Resolution at every school site and distribute it to District staff, students, and parents using usual means of communication, and that the Resolution will be translated into all languages spoken by students at home;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, the Superintendent shall report back on compliance with this Resolution to the Board at its next meeting;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, the Board directs the Superintendent to review District policies and practices regarding bullying and report back to the Board at its next meeting and communicate to staff, students, and parents the importance of maintaining a bullying-free environment for all students;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, the Board affirms that certificated District employees have the academic freedom to discuss this Resolution during class time provided it is age-appropriate; and students are to be made aware that District counselors are available to discuss the subjects contained in this Resolution; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, after-school providers and other vendors and service providers who contract with the District shall be notified of this Resolution within 30 days and required to abide by it.

[FOLLOWED BY SCHOOL BOARD SIGNATURE PAGE]

District Policy No. _________________________

Access to Education, Student Privacy, and Immigration Enforcement

School personnel must not allow any third party access to a school site without permission of the site administrator. The site administrator shall not permit third party access to the school site that would cause disruption to the learning environment.

The School Board, in Resolution No. ________, based on its educational experience and as part of its deliberative process as our governing body, has found that access to a school site by immigration law enforcement agents substantially disrupts the learning environment and any such request for access should be referred to the Superintendent’s Office immediately.

School personnel must contact the Superintendent’s Office immediately if approached by immigration law enforcement agents. Personnel must also attempt to contact the parents or guardians of any students involved.

The Superintendent’s Office must process requests by immigration law enforcement agents to enter a school site or obtain student data as follows:

- Request identification from the officers or agents and photocopy it;

- Request a judicial warrant and photocopy it;

- If no warrant is presented, request the grounds for access, make notes, and contact legal counsel for the District;

- Request and retain notes of the names of the students and the reasons for the request;

- If school site personnel have not yet contacted the students’ parents or guardians, do so;

- Do not attempt to provide your own information or conjecture about the students, such as their schedule, for example, without legal counsel present;

- Provide the agents with a copy of this Policy and Resolution No. __________;

- Contact legal counsel for the District;

- Request the agents’ contact information; and

- Advise the agents you are required to complete these steps prior to allowing them access to any school site or student data.

References

Downloads

- NEA Guidance on Immigration IssuesPDF

- Sample Safe Zone Resolution and Model PolicyPDF

- DACA Update 2025PDF

- Mass Raids FAQPDF

- Know Your Rights: Immigration EnforcementPDF

- How Educators Can Safely Engage in Immigration AdvocacyPDF

- Immigration and Schools 101PDF

- Guidance on Immigration Issues Impacting Higher EducationPDF

Are you an affiliate?