This toolkit is intended for members and their representatives who are seeking protections against discrimination based on a protected disability under federal law. As always, members should reach out to their local union representative for support in seeking a reasonable accommodation for a qualifying disability.

Scope of Federal Law Protections

Federal law, including the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Rehabilitation Act), prohibits discrimination by an employer against any applicant or employee with a disability. This section discusses who is considered to be a person with a disability under the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act. Protections against discrimination and the right to accommodations only apply if the employee or applicant has a disability as defined by the ADA or the Rehabilitation Act.

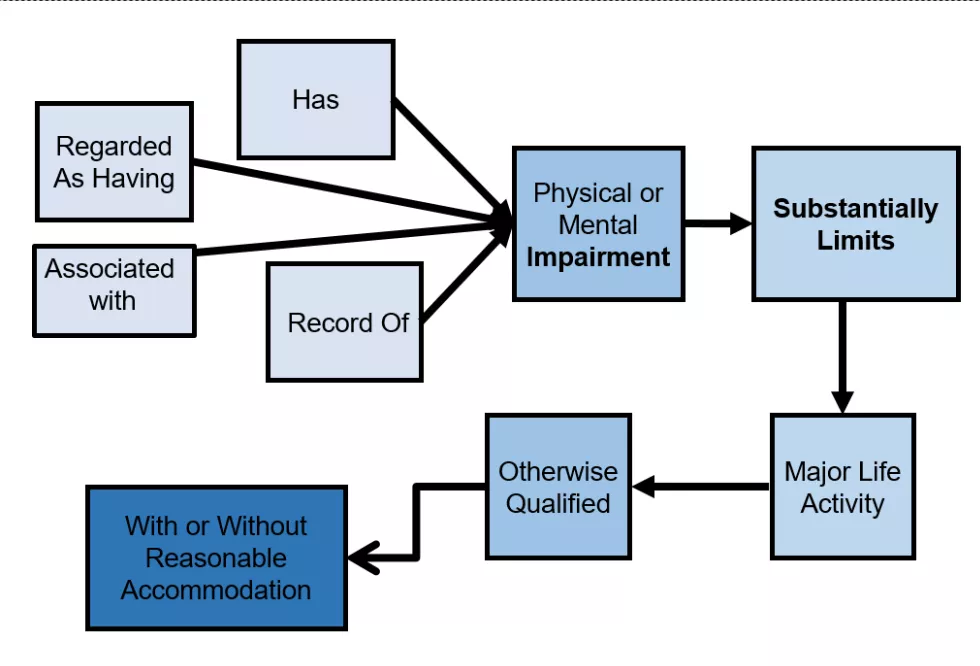

The ADA defines a person with a disability as someone suffering from a physical or mental impairment that substantially affects a major life activity (42 U.S.C. Section 12102(2)). The ADA also prohibits discrimination against an employee who

- has a record of such an impairment

- is regarded as having such an impairment OR

- is associated with someone with such an impairment.

The ADA only covers employees or applicants who have an impairment, defined as a physical or mental condition that affects one's ability to function in some capacity. A personal characteristic or temporary condition that affects one’s abilities, such as pregnancy, age, or personality traits, does not establish ADA coverage. Note that the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 prohibits discrimination based on pregnancy, and the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act of 2022 requires accommodations similar to ADA accommodations.

Who is Disabled or Regarded as Disabled?

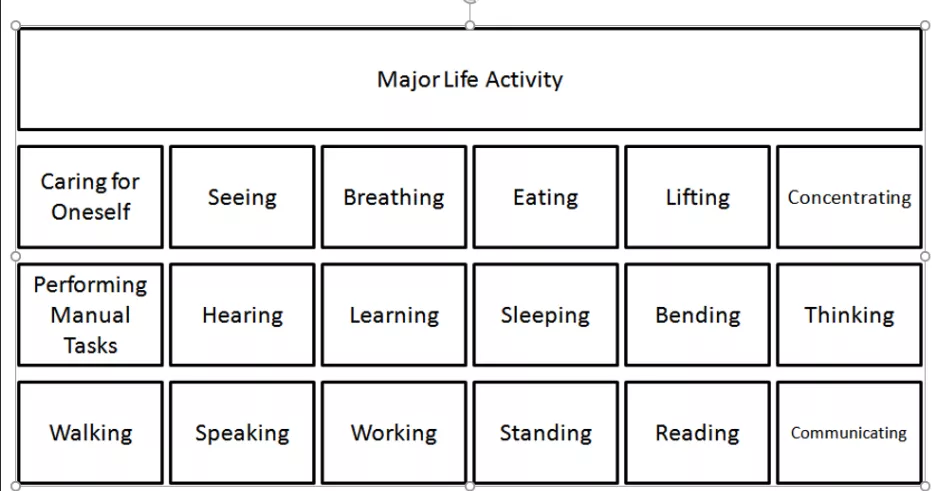

To be covered as a person with a disability under the ADA, the employee or applicant’s physical or mental impairment must substantially limit them in a major life activity. The regulations define a major life activity as a basic activity that the average person in the general population can perform with little or no difficulty.

The scope of major life activities covered by the ADA has been significantly expanded by the Americans with Disabilities Amendments Act (ADAAA) of 2008, which provides for ADA coverage if the person has an impairment that affects any one of a number of listed activities including thinking or standing, or the operation of a bodily system, such as the immune system or reproductive functions.

Advocates should urge employers to engage in an individualized analysis to determine whether an impairment substantially affects the individual in a major life activity. Employers should not make assumptions about a person's limitations based on the diagnosis alone, but should rely on a health-care provider's assessment of the person's specific capabilities. The limitation must be more than temporary to be substantial. But intermittent limitations can rise to the level of a substantial limitation.

CASE EXAMPLE: An employee with psoriasis who was unable to work during flare-ups was entitled to a jury trial on the issue of whether she was a person with a disability, because she was unable to work at all during flare-ups and suffered pain and skin irritation even during dormant periods. Cehrs v. Northeast Ohio Alzheimer s Research Center.

Employees claiming a substantial limitation on their ability to work must show more than an inability to perform one job. Instead, the employee typically must present evidence that their impairment prevents them from working in a substantial class of jobs or a broad range of jobs in the local employment market, given the employee's skills and education.

CASE EXAMPLE: Michael Troeger suffered several on-the-job back injuries. When he returned to work, the district refused to grant his requests for accommodations. At that time, Troeger's physician explained that he had recovered such that he “has no significant restrictions on driving, walking, standing, sitting, or climbing stairs,” but his lifting restriction of 20 pounds remained in effect. Troeger was not substantially limited in his ability to work without proof of an inability to work in a class or broad range of jobs, rather than a specific job. Troeger v. Ellenville Central School District.

The ADAAA clarifies that an applicant or employee can be a person with a disability if he or she has substantial limitations on a major life activity from an impairment, even if treatment or medication can reduce or eliminate the effects of that condition.

Are They Otherwise Qualified to Perform the Job?

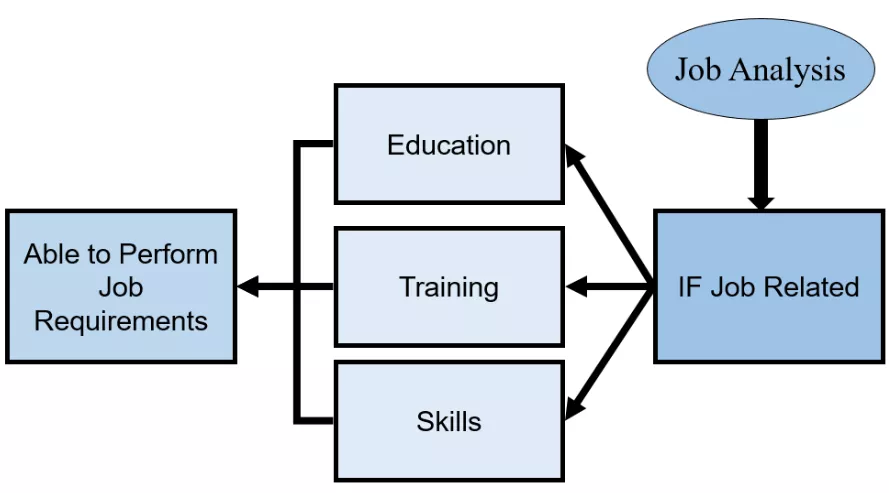

Even if an employee or applicant has an impairment as discussed above, that person must show that they are otherwise qualified to perform the essential duties of the position in question to be protected by the ADA. A person can be qualified either with or without a reasonable accommodation (discussed below). First, to be considered otherwise qualified for a position, an applicant or employee must meet the basic job requirements of the position, such as education and experience. Employers are typically given discretion in setting these requirements, such as requiring a masters degree for certain teaching positions.

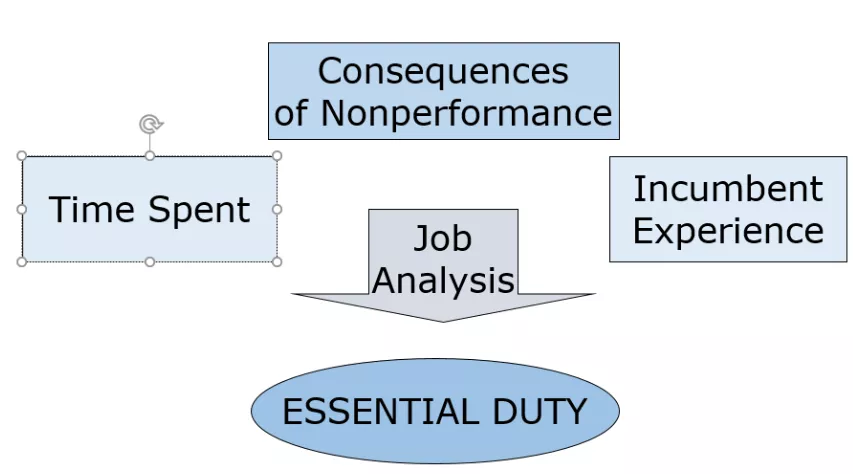

Second, the person must be able to perform the essential duties of the position, with or without reasonable accommodation, as determined by an accurate job analysis. The analysis should include the work activities and behaviors required, the context of performing those duties, and the requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities, as well as supervision.

Duties are considered essential if the employee spends a significant amount of actual time performing job duties on a regular basis, e.g., how much time a teacher’s work requires standing; the consequences of nonperformance by that employee would be significant; e.g., the employer would need to pay someone else to perform those duties, and past and current work experience of others in that position have included those duties.

A K-12 teacher may be unable to show that they are otherwise qualified if their teaching duties have always required in person attendance at work and the job description specifies that teaching take place in person. Sarkisian v. Austin Prep. School. In higher education, a university may be unable to establish that in person teaching is essential if classes have been taught online by this employee and other faculty in the past. Oross v. Kutztown Univ.

An individual’s inability to perform non-essential duties does not make them unqualified for ADA purposes; so long as the individual can perform the essential duties of the position they are entitled to the ADA's protections. For example, if a teacher cannot supervise recess when held outside because of an impairment, they could be excused from performance of that duty as an accommodation if it was only required on an occasional basis and others could easily cover that assignment without disrupting the overall supervision of recess time.

What are their Essential Job Duties?

To avoid being considered to be unqualified for a position in general, employees and applicants should be prepared to show the following:

- They do not pose a direct threat in the position.

- They are capable of regular attendance or the availability that the job requires.

- They are not engaged in current illegal drug use.

To be qualified, the applicant or employee's performance or nonperformance of the job duties, or overall presence at the work site, should not pose a direct threat to the employee, other employees or third parties. To establish a direct threat, an employer must identify a current, specific risk and make an “individualized assessment of the individual's present ability to safely perform the essential function of the job.” Chevron v. Echazabal. Without relying on perceived risks or irrational fears of others, the employer should consider the duration of the risk, the nature and severity of the potential harm, the likelihood that the potential harm will occur, and the imminence of the potential harm. 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(r)(1)-(r)(4).

CASE EXAMPLE: A person with a seizure disorder posed a direct threat where she continued to experience seizures on a regular basis and her job was considered safety-sensitive because it required the ability to respond to emergencies. Spencer - Martin v. Exxon Mobile Corp.

If an accommodation would ameliorate or eliminate that threat, then that person can be considered otherwise qualified for ADA purposes. For example, a person who has a seizure disorder could still be otherwise qualified, even if he cannot drive, if driving is not an essential job duty of his position.

CASE EXAMPLE: A deaf employee of a steel manufacturing plant was required to operate forklifts, overhead cranes, and other motorized equipment. After 12 years as an employee, the plant disallowed deaf employees from operating forklifts. The deaf employee showed his ability to communicate and otherwise safely operate the forklift with certain accommodations. Siewertsen v. The Worthington Steel Co..

- Regular and reliable attendance at the workplace is another general qualification that can be considered essential. Employers generally can require that employees come to work on time, stay for the full workday, and only take limited leave of a known duration. If a person with a disability can perform the essential job duties of the position despite attendance issues or the need for a flexible schedule, then the person might still be otherwise qualified. However, if an employee requires supervision during regular working hours, his tardiness or need for an alternative schedule could make him unqualified. Breaks could interfere with a person’s qualifications; e.g., if breaks would interfere with responsibilities to supervise a classroom. However, if a teacher can still perform their essential job duties while taking short breaks throughout the day, they could still be otherwise qualified.

CASE EXAMPLE: A lab employee who was regularly late for work was not necessarily unqualified if his duties could be performed satisfactorily in the time he was at work. Ward v. Mass. Health Research Institute, Inc..

- Illegal drug users and alcohol abusers can be deemed unqualified, even if their use is due to a concurrent addiction. Under the ADA, "a qualified individual with a disability shall not include any employee or applicant who is currently engaging in the illegal use of drugs, when the covered entity acts on the basis of such use." 42 U.S.C. § 12114(a). Note that this can include employees who misuse a prescription drug or users of marijuana, so long as their use remains illegal at the federal level. An employee typically will not be excluded from ADA coverage if they have successfully completed a supervised drug rehabilitation program and are no longer engaging in the illegal use of drugs.

CASE EXAMPLE: Martin was hired as a firefighter and EMT, and suffered from anxiety and depression. After testing positive for drugs Martin was discharged rather than being provided with counseling, as requested. He had utilized EFR's Employee Assistance Program (EAP) to seek care for his depression and drug use, and he had not used drugs for a significant period of time. The court refused to dismiss Martin's claim of discrimination under the ADA because it was plausible that he could invoke the ADA's safe harbor provision due to his alleged use of EAP as a rehabilitation program. Martin v. Estero Fire Rescue.

Keep in mind that a person with a disability may be otherwise qualified if a reasonable accommodation would enable them to perform the specific or general duties of the position.

What is an Employer’s Duty to Accommodate an Individual with a Disability?

As discussed above, an applicant or an employee is otherwise qualified for a position if a reasonable accommodation would enable them to perform duties of the position that he or she could not otherwise perform because of a disability.

Employers must provide accommodations that are reasonable, which can include “any change or adjustment to a job or work environment” that permits completion of the application process or performance of essential job duties. EEOC, The ADA: Your Responsibilities as an Employer. Reasonable accommodations can include changes in the physical work environment, equipment needs, or hours of work. 42 U.S.C. § 12111(9); Job Accommodation Network. The undue hardship defense, discussed below, may relieve an employer of its obligation to provide a reasonable accommodation.

An employer is only required to provide a reasonable accommodation if that need is known to the employer. That need can become known because it is obvious; e.g., accessibility for a chair user; or through a request from an applicant or employee. In addition, the circumstances may give the employer enough information to know that an accommodation may be needed, so that the employer should inquire further. For example, an employer may have an obligation to begin the accommodation process if the employee starts having difficulties performing the duties of the position and the employer has reason to believe that the problems result from a disability.

What is an Employer’s Duty to Accommodate an Individual with a Disability?

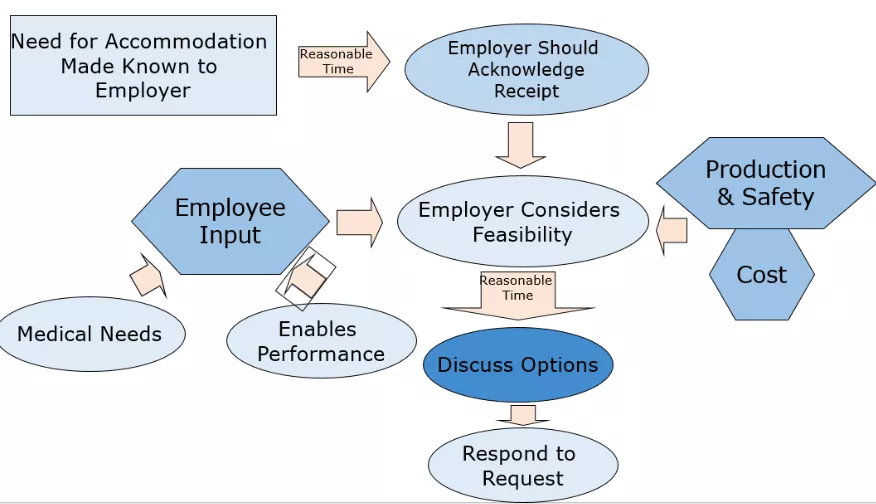

Employers Must Engage in an Interactive Process with the Individual

Any person seeking an accommodation should invoke the ADA’s requirement that the employer interact with the employee or applicant with a disability to discuss the best way to accommodate that person's disability. This duty to interact is triggered by information that is sufficient to provide the employer with adequate notice of ''both the disability and the employee's desire for accommodations for that disability." Taylor v. Phoenixville Sch. Dist.. The employee seeking an accommodation must be sure to tie the request to a disability (as defined above) and continue to assert that request if circumstances change.

CASE EXAMPLE: A teacher who sought both leave and a transfer as accommodations for her PTSD showed that the district failed to provide her with a transfer as an accommodation after she returned from her requested leave. While on leave, the teacher informed the district that she was able to return to her position, and her doctor then certified that she was able to return to her previous position without restrictions. However, summary judgment for the district was denied because the teacher continued to assert her request for a transfer after she returned from her leave, and the district failed to interact with her about this request. Lawler v. Peoria Sch. Dist. No. 150.

The interactive process should allow the employee with a disability to have input, rather than simply being presented with the employer's suggestion for an accommodation. The burden is on the person with a disability to identify an accommodation that is reasonable and to show that the requested accommodation makes them qualified to perform the essential duties of the position.

CASE EXAMPLE: Munoz’s supervisor was aware of Munoz’s sleep disorder and injuries from a car accident, and received at least one email from Munoz after her return to work alluding to being in “pain from my therapy.” Munoz asked her supervisor for periodic days off and opportunities to stand and stretch after her return to work. The employer did not initiate a conversation with her about how to support her return, or follow up after Munoz spoke with her supervisor. Summary judgment for the employer was denied because a jury could find that employer failed to engage in the interactive process, and could draw an inference of bad faith. Munoz v. Nutrisystem, Inc..

As part of the duty to interact, an employer must consider the feasibility of the requested accommodation, including weighing the cost of the requested accommodation against the benefit it would provide to the person with a disability, and any effects the accommodation would have on the employer's productivity and safety concerns. If more than one accommodation is reasonable and could enable the employee or applicant to perform the essential duties of the position, the employer can choose between those accommodations. As part of this process, the employer can seek further information about the need for accommodation by contacting the employee’s doctor and/or meeting with the employee to explore potential accommodations.

CASE EXAMPLE: An ESL teacher who sought to be moved to a less stressful classroom and specific planning periods as an accommodation showed that the district failed to engage in the interactive process when the principal failed to attend scheduled meetings to discuss the accommodations, while providing similar accommodations to other teachers. Danielle-Diserafino v. Dist. Sch. Bd. of Collier Cty..

Some accommodations may take time to put in place, so some delay in fulfilling an employee's request may be reasonable.

Employers Must Provide Reasonable Accommodations

An accommodation should address the impairment identified by the employee. If an accommodation offered by an employer does not enable the employee to perform their essential job duties, or still allows the impairment to be exacerbated, then that accommodation may not be reasonable. Cole v. Kenosha Unified Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ.. In that situation, the employer would be required to offer some accommodation that was reasonable.

Employers are only required to provide reasonable accommodations. Although reasonableness often depends on the specific situation, examples of requested accommodations that have generally been found by courts to be reasonable include all of the following:

- a change of working hours or schedule, if performance of essential duties is not inhibited

- temporary leave for a known period of time

- transfer to a vacant position for which the person is qualified

- release from or reassignment of tangential or nonessential job duties

- provision of equipment, aids or services, such as readers, interpreters and other assistive technology

CASE EXAMPLE: AutoZone’s employee, John Shepherd, was promoted to the position of parts sales manager and 80% of his job was sales-related. The other 20% of Shepherd's job included the tasks that created problems for him, such as stocking shelves and mopping floors. Based on evidence that mopping duties could be delegated to other employees, and the amount of time spent mopping was perhaps an hour a week, the court upheld a jury verdict in Shepherd's favor, based on a finding that mopping was not an essential function of Shepherd's position. EEOC v. AutoZone, Inc..

A change in schedule can be a reasonable accommodation if the employee is still able to perform their essential job duties.

CASE EXAMPLE: A teacher assistant and crisis manager sought permission to arrive at 9:00 am because of his health conditions. His health care provider had recommended a later start time to give him adequate time in the morning to eat and take his medications before arriving at work. The district insisted that he needed to be at work from 8:15-3:45 each day. The district’s motion to dismiss was denied because it failed to respond to his request for a later start date, and because the teacher alleged that there were other school employees who could cover his duties before his requested start time. Calloway v. Durham Cty. Bd. of Educ..

Prior to the COVID 19 pandemic, courts regularly held that in-person attendance was an essential function of most jobs, “especially those involving teamwork and a high level of interaction … .” EEOC v. Ford Motor Co.. But the experience of employers and employees with remote work since 2020 have changed the landscape and made remote work a reasonable accommodation for many employees. One court noted that “In the post-COVID pandemic economy and with the advent of new technologies making working from home more feasible, we must now assess whether in-person attendance is essential on a context-specific basis.” Smithson v. Austin.

While remote work may be a reasonable accommodation in a variety of workplaces, Montague v. U.S. Postal Service. See EEOC, Work at Home/Telework as a Reasonable Accommodation, pre-K to 12 schools generally have not been work locations in which remote work has been found to be a reasonable accommodation. For example, in one recent case, a long term substitute teacher who broke her hip and was terminated after she utilized her leave, lost on her disability claim because the court found that regular in-person attendance was an essential function of her job. Sarkisian v. Austin Prep. School.

CASE EXAMPLE: Annie Ray sought permission to teach remotely as an accommodation for her numerous health issues. The district moved to remote teaching in Spring 2020, but returned to in person teaching in Fall 2020. The district showed that in person attendance was essential, based on the duties of monitoring a classroom and disciplining students in the teacher job description. The court noted that the temporary move to online teaching “does not mean that employees were permanently excused from performing those functions.” The district would have been required to reassign essential job duties if Ray was allowed to continue to teach remotely. Ray v. Columbia Brazoria Ind. Sch. Dist..

Allowance of service and support animals in the workplace can be a reasonable accommodation if supported by a health care provider’s recommendation.

CASE EXAMPLE: A high school teacher sought permission to continue to bring her service dog to work in connection with her Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia that led to panic attacks. The teacher had been allowed to bring a service dog to work during the previous year, while working in a different building. The district argued that students in the larger school setting could be allergic to or afraid of dogs. The court denied summary judgment for the school because the teacher showed that there were questions of fact about whether the service dog was the only reasonable accommodation for her condition, and whether the other accommodations offered by the school were reasonable. Clark v. Sch. Dist. Five of Lexington & Richland Ctys..

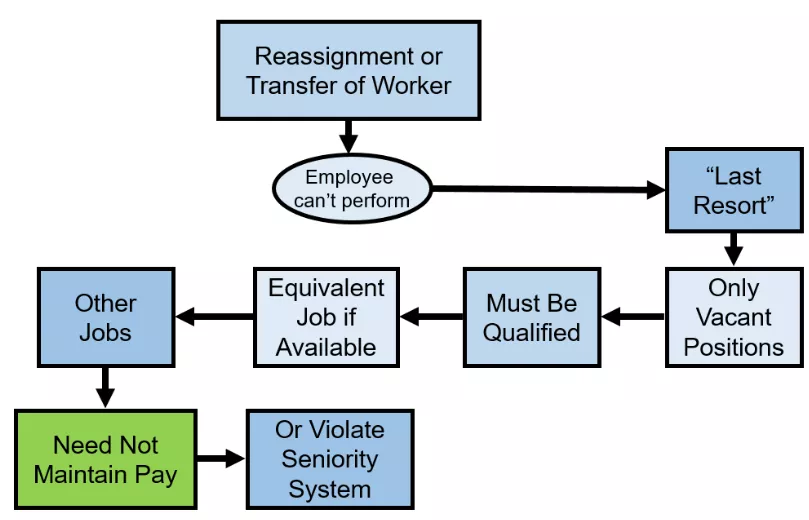

Employees can seek reassignment or transfer to another vacant position as an accommodation, even if the employee can no longer perform the duties of a current position. Cravens v. Blue Cross Blue Shield. An employee can request a reassignment or transfer to another vacant position for which they meet the minimum qualifications. In response to a request for reassignment, the employer need not create a position or remove another person from a position. If another employee is entitled to the position sought by the employee with a disability, under a seniority policy in place, then the transfer would not be a reasonable accommodation. U.S. Airways v. Barnett.

Employers Can Refuse to Provide Unreasonable Accommodations

An employer can argue that they are not required to provide an accommodation because it is unreasonable. The burden is on the person with a disability to propose a reasonable accommodation, but in considering that accommodation, an employer must consider the individual circumstances of the position and the employee who has made the request. Before deeming the accommodation to be unreasonable, the employer should engage in the interactive process (discussed above) to confirm the facts the employer is relying upon to deny the request and to discuss alternative accommodations which could be deemed reasonable.

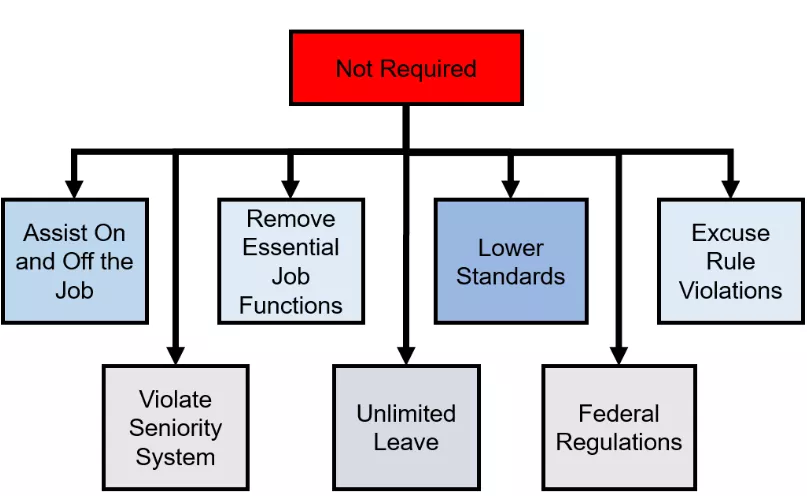

Because the focus of any accommodation is to enable the employee to perform the essential job duties, an employer is not required to provide an accommodation, such as adaptive equipment, for the employee's personal use. In addition, an employer is not required to provide more than what the employee's health-care provider recommends.

As a general rule, courts tend to find the following requested accommodations unreasonable.

- Assigning another employee to provide assistance on to perform essential job functions, or otherwise excusing the employee from performing those duties

An employer need not excuse a person with a disability from the performance of essential job duties. Likewise, an employer is not required to create a position that would not otherwise exist without the request for an accommodation. An employer need not create a light duty position on behalf of an employee with a disability, if such a position would not otherwise exist. Similarly, an employer typically is not required to change an employee’s supervisor, even if that supervisor has engaged in harassment of the employee. - Lower standards or excuse rule violations

An employer can still hold employees with disabilities to the same performance standards and workplace rules that are imposed on other employees. An employee can ask for an exception to one of those rules or standards, or accommodation to help them meet those goals, but such an exception would only be reasonable if the employee were still able to perform the essential job duties. - Unlimited leave

An employer need not grant leave of an indefinite duration as an accommodation. Keep in mind, however, that under the Family and Medical Leave Act, an employee may qualify for at least 12 weeks of unpaid leave, and additional leave may be reasonable. - Violate federal regulations

An employer typically need not violate regulations which address public safety or other public concerns to accommodate someone with a disability

CASE EXAMPLE: A teacher was not entitled to the accommodations she sought related to her knee surgery when the district offered her permission to use a wheelchair and a stool when standing or walking with students was required. The district was not required to provide her with an assistant to walk with or observe her students, or excuse her from the performance of hall monitoring duties, which were all essential parts of her job. Hargett v. Jefferson Co. Bd. of Education.

The reasonableness of an employee’s request for leave as an accommodation depends on whether the employee can still perform their essential job duties despite their use of leave. Such a request may go beyond the 12 weeks of leave available under the Family & Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Sporadic leave is less likely to be deemed reasonable. Leave can be a reasonable accommodation if it is for a known duration and the employee will likely be able to return to work at the end of the leave. In contrast, if the employee cannot provide assurances that they will be able to return to work at a specific time, and in a reasonable amount of time, then that leave could be determined to be unreasonable.

CASE EXAMPLE: A teacher failed to show that a school did not provide her with additional leave as a reasonable accommodation (rather than terminating her employment) when she failed to provide the district with a return to work release from her health care provider and she worked part time for another district during her leave period. Owens v. Calhoun Co. Sch. Dist..

Appellate courts are split as to whether an employer must accommodate an employee regarding issues related to commuting. See Colwell v. Rite Aid Corp (requiring assistance related to employee’s ability to get to work) and Unrein v. PHC-Fort Morgan, Inc. (no duty to accommodate an employee’s commute).

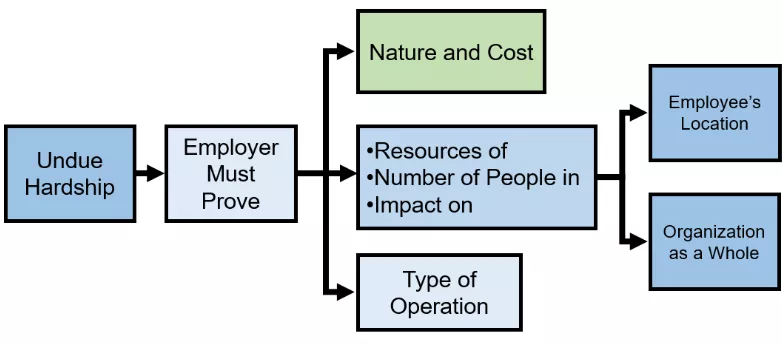

Employers Can Claim an Accommodation Will Impose an Undue Hardship

Employers can avoid providing a requested accommodation if they can prove that it would place an undue hardship on the employer. The proof of hardship must be individualized, based on the limitations caused by the person's disability and the work requirements, as well as the employer's resources and operation.

CASE EXAMPLE: Lauren Searls applied for the position of nurse clinician at Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH). Searls had a hearing impairment; and requested access to American Sign Language (“ASL”) interpretation. Her position required effective verbal communication and interpersonal skills and communication was listed as an “essential job function.” JHH determined that Searls would require a team of two interpreters with her at all times at an annual cost of $240,000, compared to the JHH's Department of Medicine’s operational budget of $88 million and JHH’s overall operational budget of $1.7 billion. JHH failed to show that provision of ASL would impose an undue hardship, despite the absence of a budget item to cover the accommodation. Searls v. John Hopkins Hospital (D. Md. 2016).

The undue hardship determination weighs the following considerations:

- Nature and cost of the accommodation relative to its benefit to the employee requesting it

- Resources of the facility where the employee works, such as the assigned building, and the overall financial resources of the employer, such as the school district.

- Size, location and type of facility where the employee works, such as the school building, and overall work performed in that location.

- Impact on the employer’s operations, including productivity at the location, such as school building, where the employee works and impact on the employer’s overall operations; i.e., the entire school district.

- Type of operation, and whether the accommodation would significantly interrupt those operations or affect its purpose; e.g., the educational purpose which the employee supports.

A school can try to establish an undue hardship based on the school’s operational needs and educational goals would be undermined by granting the requested accommodation, even if that accommodation is reasonable. Blanks v. Springfield Public Schools.

CASE EXAMPLE: A detention center was able to show that allowing an employee to work an 8 hour shift as an accommodation would impose an undue hardship. Other staff worked 12 hour shifts, and the center was still regularly short-staffed. Allowing her to work an 8 hour shift would require other staff to work longer hours and extended shifts. Anderson v. Harrison Co., Miss..

The employer should consider whether the costs are excessive relative to the benefit received by the employee. For example, if the accommodation will mean the difference in the continued employment of the person with a disability, then a higher cost may be justified.

CASE EXAMPLE: An employee’s request for an irritant-free work environment was found to place an undue financial and administrative burden on the employer because the changes required would cause a fundamental alteration in the nature of the program operated by the employer. In comparison to this burden, the benefit was limited, since employee would still have required some period of leave before returning to work even in an irritant-free environment. Buckles v. First Data Resources.

In making a determination as to whether an accommodation places an undue hardship on an employer, courts will not excuse the accommodation based on an employee's salary, fears or prejudices of other employees, or impact on employee morale.

What Can an Employer Inquire about and ask for in terms of Medical Documentation?

Under the ADA, there are two general rules for interviewing applicants:

- Questions which relate to the applicant's ability to perform the job are generally acceptable.

- Questions which ask an applicant for private health information are generally prohibited.

EEOC's Enforcement Guidance on Disability-Related Inquiries and Medical Examinations of Employees under the ADA.

Inquires during Application Process

The ADA’s prohibition against asking questions about an applicant's health or disability on an application or during an interview applies regardless of whether an applicant is defined by the ADA as a person with a disability. This means that applicants should not be asked any question that is likely to elicit information about a disability.

CASE EXAMPLE: Peter Mir has suffered from hip problems throughout his life and has had a number of surgeries on his right hip, causing him to walk with a pronounced limp and use a cane. While escorting Mir from one building to another, the interviewer asked Mir questions regarding his ability to walk, and later asked questions regarding the nature and extent of his physical limitations, including inquiries as to Mir's short and long-term prognoses and a timeline of when the injuries occurred. The court refused to dismiss Mir’s claim based on this evidence that the employer made improper inquiries under the ADA. Mir v. L-3 Communications Integrated Systems, L. P..

Because a current illegal drug user is not protected under the ADA, inquiries about an applicant's current use of illegal drugs is permitted. However, an employer should never ask whether an applicant is a drug addict or an alcoholic, because both are considered to be disabilities under the ADA.

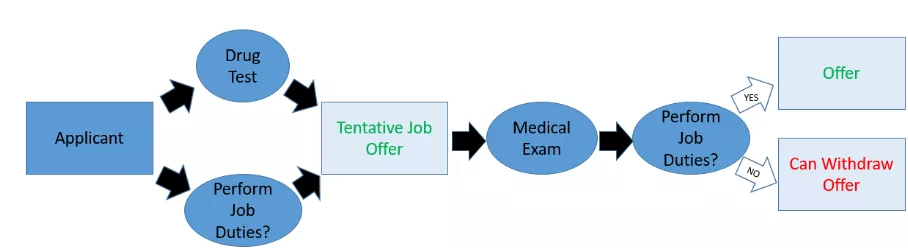

Medical Examinations after Offer

Under the ADA, medical examinations cannot be required of applicants before an offer of employment is made, regardless of whether the applicant is defined by the ADA as a person with a disability. However, a conditional offer can be granted with the stipulation that the decision will rely upon examination results that indicate the person is physically and mentally capable of performing the job. Once a tentative job offer is given, the employer can make health related inquiries and require a medical examination.

Medical examinations of an applicant, after a conditional job offer has been given, need not be job-related and consistent with business necessity. However, if certain criteria related to a medical examination are used to screen out an employee or employees with disabilities as a result of such an examination, that criteria must be job-related and consistent with business necessity, and performance of the essential job functions cannot be accomplished with reasonable accommodation as required. 29 C.F.R. §1630.14(c)

CASE EXAMPLE: Robert Chalfant, who had arthritis, had undergone carpal tunnel and heart by-pass surgeries. Chalfant applied for a position with Titan after having these medical issues. Titan claimed, after the completion of Chalfant's medical examination, that the position was eliminated. The jury award including $100,000 in punitive damages was upheld based on evidence of a link between Chalfant's disability and the withdrawal of his employment offer. Chalfant v. Titan Distribution Inc., 475 F.3d 982 (8th Cir. 2007).

The results of the medical examination can only be used to withdraw an offer if they reveal one of the following conditions:

- the applicant is unable to perform essential functions of the position OR

- the applicant would pose a direct threat to himself/herself or others in the position.

Employers should consider whether an accommodation could render the person qualified, as discussed above. See discussion of direct threat under Otherwise Qualified section above.

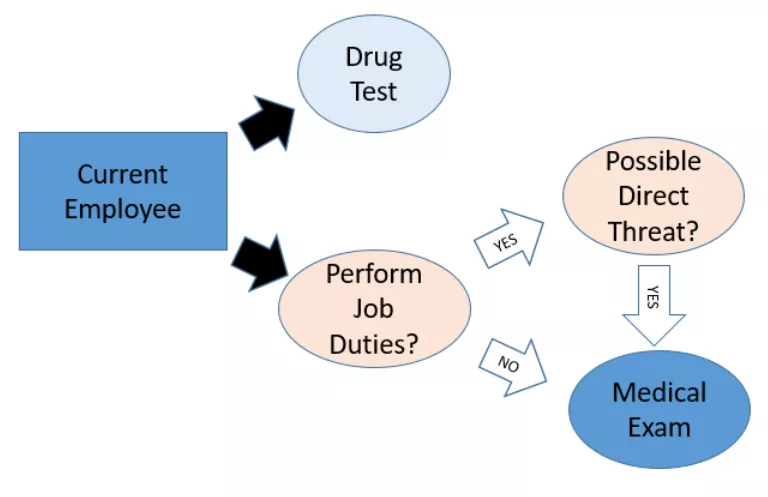

Examinations of Current Employees

With respect to current employees, employers cannot require a medical examination unless that examination is job-related and consistent with business necessity. 29 C.F.R. §1630.14(c). Testing of current employees should be limited to determining whether the person is able to perform the essential job duties of the position. 29 C.F.R. §1630.14(c). Disability-related inquiries and medical examinations that follow up on a request for reasonable accommodation, as well as periodic medical examinations and other monitoring under specific circumstances, also may be job-related and consistent with business necessity.

Testing of current employees should only take place if based on an employer's knowledge about a particular employee's medical condition, or if the employer has observed performance problems, and reasonably can attribute the problems to the medical condition. An employer also may rely on credible information or observation of a medical condition that could impair his/her ability to perform essential job functions or would pose a direct threat. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)'s Enforcement Guidance on Disability-Related Inquiries and Medical Examinations of Employees under the ADA.

The ADA requires that employers treat any medical information obtained from a disability-related inquiry or medical examination as a confidential medical record. Under the ADA, employers may share such information only in limited circumstances with supervisors, managers, first aid and safety personnel, and government officials investigating compliance with the ADA.

Checklists

Disability Rights Coverage Checklist: Use this checklist to determine if a person is covered as a “person with a disability” under the Americans with Disabilities Act, as amended by the Americans with Disabilities Amendments Act.

Accommodation Checklist: Use this checklist to determine if a person is entitled to changes to the work requirements or environment of job they seek or hold as an employee.

Undue Hardship Checklist: Use this checklist to determine if an employer is required to provide a reasonable accommodation to an applicant or employee. Employers need not establish undue hardship if the person seeking accommodation is not a person with a disability, or if the accommodation sought is not reasonable.

Join Our Movement