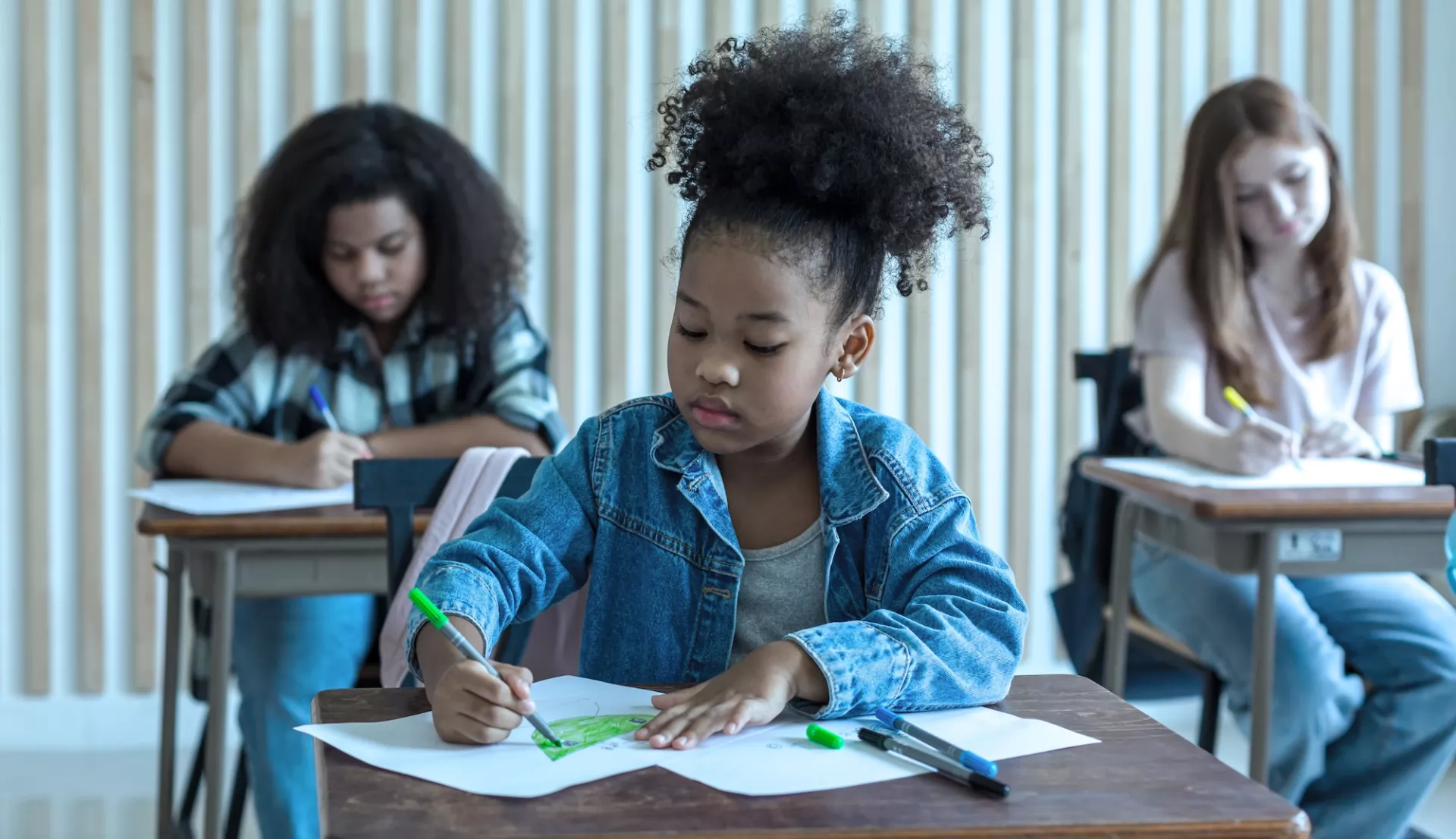

When I stepped into my first classroom as a leave replacement third-grade teacher at Washington Elementary School in Roselle, New Jersey, during the 2014-2015 school year, I encountered third-grade students who were a vibrant mix of cultures and backgrounds—African American, Hispanic, Jamaican, Haitian, Cuban, and Central and South American. Most of the students were born in the U.S., but a few were recent immigrants navigating English as their second language.

The classroom had students who were eager, determined, and were high-functioning literacy and math mavens. These students were able to meet all of New Jersey state standards for literacy and math by being able to “read closely to determine what the text says,” “ask and answer questions, and make relevant connections to demonstrate understanding of a text,” “use multiplication and division within 100 to solve word problems,” and “fluently multiply and divide within 100.”

On the other hand, there were students in class who struggled with basic reading, writing simple sentences, and completing third-grade math work. Third grade is a pivotal year for academic growth—falling behind could mean facing even greater challenges in the years ahead.

That’s where Title I changed everything.

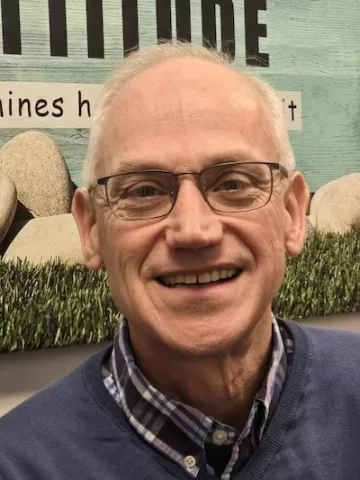

Becoming a Teacher Through an Unexpected Path

In September 2011, after nearly seven years at a Newark childcare resource and referral agency, I sat in a meeting room with four colleagues. The news was swift and unexpected—we were being let go due to statewide funding cuts in education and social services by Republican governor Chris Christie. We were offered severance packages and given the option to reapply for a different position. As I walked out of the building, a mix of emotions—rejection, uncertainty, and determination—swirled inside me.

That same day, my closest work friend, Tyheria Reeds, called me. “Why didn’t you apply for another position?” she asked. I took a deep breath. “Because,” I said with certainty, “I’m going to become a teacher.”

With unemployment insurance paying for me to finish my master’s degree, I committed to becoming a teacher. By the summer of 2012, I obtained a substitute teacher certificate and stepped into my first classroom as a substitute teacher and paraeducator in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Two years later, I obtained a Certificate of Eligibility (CE) to teach in New Jersey schools. I applied for a teaching position at Washington Elementary School in Roselle and became a 3rd grade leave replacement teacher in the 2014 - 2015 school year.

This position was partially funded by Title I, a program I had heard of but never fully understood—until I saw its impact firsthand in my classroom.

What Title I Does

Title I was established by Congress in 1965 to provide critical federal funding to support preK-12 schools in low-income communities. Almost two-thirds of U.S. public schools are currently Title I eligible. To bolster students who are academically struggling, Roselle uses its funding to pay the salaries of additional teachers, including basic skills and instructional coaches who provide academic support in general education classrooms. The district also uses Title I for before and after school tutorial programs, and Family Resource Nights events.

At Washington Elementary School, there were two Title I-funded school district employees who taught basic skills. The basic skills teachers would “push in” and “pull out” students who were struggling in reading and math, work with them in small groups, give additional support, and get the best outcomes.

One of the Title I teachers became my mentor and taught me how to teach the district’s curriculum, institute classroom routines, and make classroom management seamless.

The other Title I basic skills teacher was the wise sage of the school who planned events, would rapidly help colleagues, and was a resourceful, accomplished, and decorated educator who brought out the academic best in the students that she took into her small groups.

Elijah’s Story

One of my students who benefited from Title I was Elijah. Elijah’s mom attended one of the district’s Family Resource Nights, and when I started as a leave replacement teacher in October 2014, we met.

During our meeting, Elijah’s mom said directly, “Mr. Sekou, Elijah needs help with reading and math. How are you going to support him?”

Because of her advocacy, I gave Elijah extra support and placed him with the small group basic skills teacher. In addition to getting extra support from me, Elijah received daily small group support in math and reading. On some days, the students in the small group that Elijah was in received extra instruction in class. On other days, the students in the small group received instruction on reading, sentence structure, and mathematics in the basic skills teacher’s office.

Elijah's mom also ensured that he attended the Title I-funded after-school academic program. Gradually, I started to see improvement in Elijah’s academic performance. By the 4th marking period, I was extremely proud to place on Elijah’s report card a B for reading and a B for math. Elijah was able to improve because his mom advocated for him, he worked hard in class during his small group sessions, and he attended the after-school program.

But Elijah's academic elevation would not have happened if it wasn’t for Title I.

‘Close Some of the Gaps’

The legacy of Title I paying the salaries of basic skills teachers to work with struggling students continues at Washington Elementary School.

Miguel Ruiz, a basic skills math teacher at Washington Elementary School, values the opportunity to work with these students. “I can pull them during their second math period and just give them a different perspective, maybe touch on some different topics that the classroom teacher is not able to touch on. It is a great opportunity to meet with them and close some of the gaps.”

In addition to funding teachers' salaries and before and after school programs, in Roselle, Title I funds a summer program. Ruiz says that “the summer program that Title I funds is incredible. I love the fact that we can meet with students over five weeks because the summer slide is real. The fact that we can do some work over the summer versus going two months without anything.”

The Threat to Title I

But with the Trump Administration slashing nearly 50% of the Department of Education’s staff, Title I could be next on the chopping block.

For small districts like Roselle, even a modest cut could mean losing essential funding for teachers, after-school programs, and summer learning initiatives.

William Jones is the Supervisor of ESSA/Title I in Roselle Public Schools and worries about the impact of these potential cuts. Even a five percent reduction, he says, would be devastating.

“For a small school district like Roselle, we would have fewer after-school programs without Title 1. If our funding is pulled, we may not have the teachers during the day.”

Cutting Title I funds would affect every corner of this country. The program doesn’t just affect students in the urban areas and cities. It affects children in the suburbs and in rural communities across this country. It affects children of all colors, ages, and backgrounds.

“The farmland depends on Title I just as much as the cities do,” says Jones” Everybody is impacted by this. We get funding based on need. The suburbs may not get as much as the cities do. But they are going to feel the impact too if these funds are cut.”

Title I is a lifeline. It shapes classrooms, supports struggling students, and gives every child, regardless of zip code, race, or economic status, a chance to succeed. As I continue my journey as an educator, I remain a staunch advocate for Title I—not just for my students, but for the countless others whose futures depend on it.

Sundjata Sekou (pronounced Sund-Jata Say-Coo) is a Hip-Hop loving, “dope,” Black, male, elementary school teacher in Irvington, N.J., and NEA’s 2024 – 2025 writer-in-residence. With support from his union sisters and brothers in the NJEA Members of Color Affinity group, he received the 2024 New Jersey Education Association Urban Educator Activist Award. You can follow him on Instagram @blackmaleteacher and email him at [email protected].