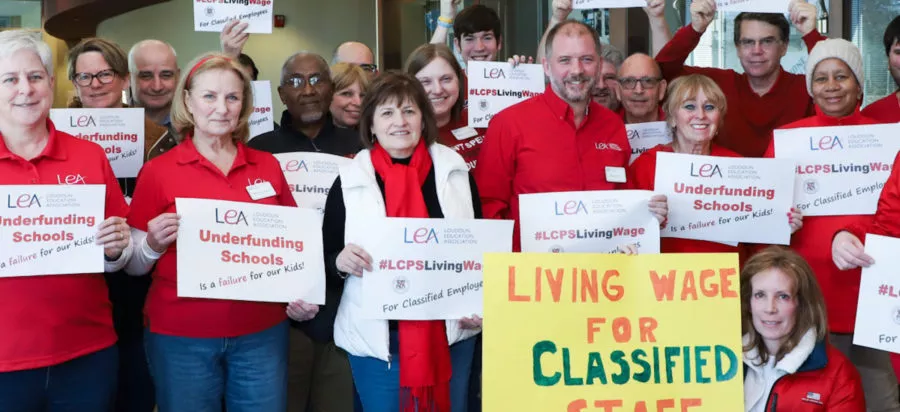

ESP members of the Loudoun Education Association rally for a living wage at a board of supervisors public hearing. (Photo: Philippe Nobile)

In protest of low pay and cuts to education funding, education support professionals (ESP) in Virginia’s Loudoun County organized a campaign last December they called, “A Push for Living Wage.”

Their objective: An increase in wages and salary steps while opposing a reduction in force (RIF).

Their plan included blasting school board members with emails, generating local newspaper and social-media coverage, and rallying at board meetings in matching red T-shirts while carrying colorful homemade signs. The plan worked, to some extent.

At a March hearing of the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, several dozen ESP members of the Loudoun Education Association (LEA) showed their tenacity by donning red T-shirts, waving poster board signs, and distributing pamphlets encouraging a visit to their Facebook page: #LCPSLIVINGWAGE.

“We are here to educate the public about the abysmal pay of many employees who work 12 months a year, eight hours a day, and are paid less than $32,659, which is a living wage for Loudoun County (for one adult),” said David Palanzi, president of LEA, which consists of 3,400 teachers and 630 classified employees.

“Loudoun needs schools where our custodians and all employees are paid a fair wage for their hard work,” he told board members. “The budget should not be balanced on the backs of classified employees.”

As news of the living wage campaign spread within the district’s 90 worksites, Palanzi says more and more classified employees became active within LEA. In recent months, there has been a slight membership increase among ESP members.

At an April 24 board meeting, just five months after starting the living wage campaign, board members voted unanimously to increase pay by 3 percent for ESP, teachers, and other employees beginning in September, while not inducing a RIF.

“The living wage campaign really caught on, particularly with one conservative member of the board who we weren’t sure we could reach,” Palanzi said.

While curtailing campaign efforts for the current school year, LEA officials are in the process of working with several ESP leaders to keep the momentum going in their efforts to gain a living wage for ESP members during the next budget cycle.

“We still have not achieved a living wage for ESP, but we are getting there,” Palanzi said.

Moonlighting to Make Ends Meet

Located about 60 minutes west of Washington, D.C., Forbes magazine has called Loudoun “the richest county in the nation.” Yet many of the county’s school employees work second and third jobs to make ends meet. Even then, many cannot afford to live in the district due to high housing costs and steep property taxes.

Mohamed Osman lives outside the district and earns $31,000 working eight hours a day as a district bus driver. He has a second job in the evening that keeps him away from home until midnight.

“Some of the drivers here work as Uber drivers to survive,” Osman says.

Megan Fay is a fulltime health clinic specialist for the district with a physician assistant’s medical license and master’s degree in physiology. She earns $29,000 a year.

“My job requires making calculations for insulin doses and administering insulin to children with diabetes,” she says. “I’m here advocating for a living wage.”

Karen Tyrrell is a technology assistant at Belmont Ridge Middle School with 13 years of experience and a bachelor’s degree from Duke University.

“After all these years, I still don’t earn a living wage,” says Tyrrell.

Technology assistant Paula Vorndran has worked 17 years for the district. Married, she earns less than $21,000 a year.

“If I was on my own I would not even be able to afford an apartment in Loudoun,” says Vorndran, who has a bachelor’s degree in broadcast communications. “I like the job, the people, and working with students.”

Under the current pay system that includes 28 steps, technology assistants are not paid a living wage until step 18 ($33,103). Health clinic specialists like Fay will not earn a living wage until step 13 ($32,861).

The Long Commute

One of the biggest issues for bus drivers who live outside county lines is their early morning commute.

“Many of the bus drivers live in neighboring counties an hour’s drive from Loudoun,” says bus attendant Maryann McHugh, who earns $26,000 annually after 12 years on the job. “Some drivers get up at 3:30 a.m. to be at work on time and don’t get home until around 7:00 p.m. They have dinner, go to bed, then do it again the next day.”

In Loudoun, bus drivers do not begin to earn a living wage until step 10 ($33,306). The highest step pays drivers $53,582. Even after reaching step 28, a school cafeteria worker earns far less than a living wage: only $22,322. Paraeducators do not earn a living wage until step 23 ($32,823).

“Many of us live paycheck to paycheck,” McHugh says. “But we remain hopeful.”