Key Takeaways

- Students need access to physical books that reflect their background and personalities.

- Choosing books intentionally based on students’ interests can help them see reading as entertainment the way they do video games.

- Having students engage with texts through crafts or talking about it can help develop their reading comprehension.

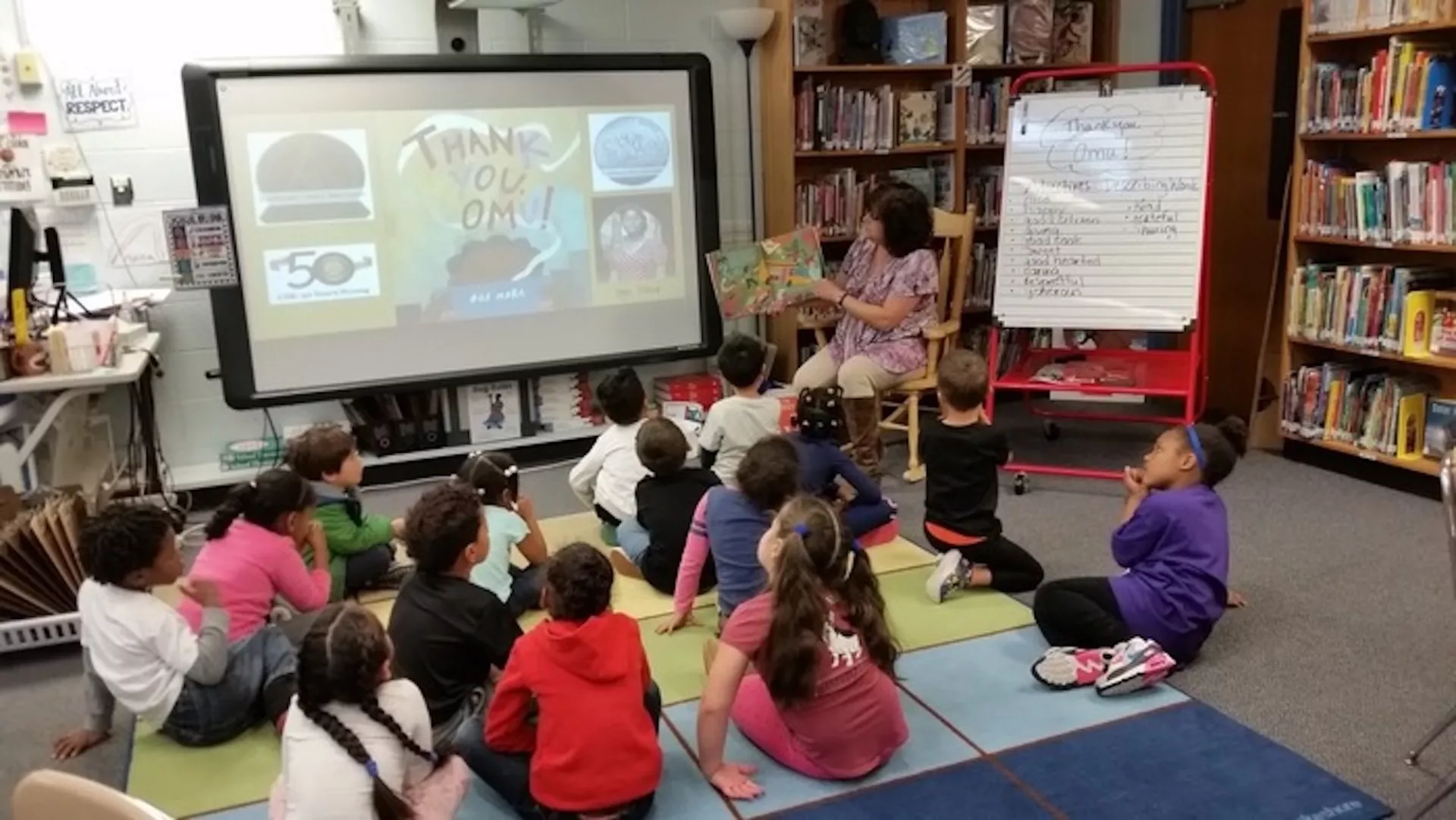

When Marcia Hoyle Walkama started working in Brockton Public Schools, the average books in the library were around 30 years old. There were almost no books that reflected her students, who were from Haiti, Cape Verde and the Dominican Republic.

In Brockton, Massachusetts, 49% of students’ first language is not English and 74% qualify as low-income. Hoyle Walkama says this is where the importance of the school library comes in.

“The kids from Brockton wouldn't have access to books at home,” Hoyle Walkama says. “And I'd say very, very few go to the public library. And I try to make a big deal about having books that interest them, which I think makes a whole lot of difference.”

Like many schools, Brockton is experiencing budget problems. To buy new books, Hoyle Walkama has been relying on grants and donations from outside organizations, including one from the NEA Read Across America Grant, from which the district received 700 diverse books.

“I can't imagine that I could even engage a kid if I didn't have these new books,” Hoyle Walkama says. “It's crucial for kids to have an interest in checking the book out and sharing it.”

The Physical Books

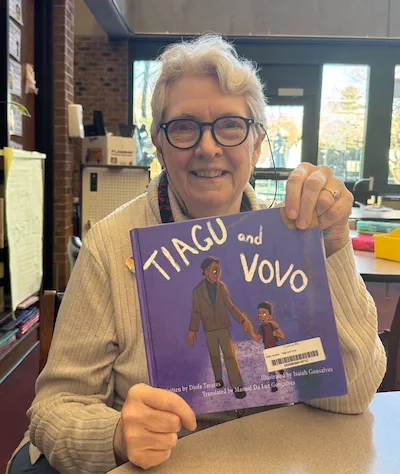

Hoyle Walkama says having books that look like her students has made a huge impact. Her students particularly love one dual-language book,”Tiagu and Vovo,” which is printed in English on one side, and when flipped over, Cape Verdean Creole on the other.

“I just ordered another four of those books because I can't keep them in stock,” Hoyle Walkama says. “The kids get the biggest kick out of reading it in English and then flipping it over and being able to take it home and read it with somebody at in their native language.”

Hoyle Walkama has been updating her library to reflect her student’s interests, too, like books about soccer.

“If you pick books that interest them and books [with characters who] look like them, or books that you read aloud,” she says, “they want to know more, they want it in their hands.”

The NEA has a list of book recommendations that uplift the perspectives and experiences of disability, which reflect the experiences of students across the country --- 95 percent of students with disabilities are in public schools. NEA grants are reopening at the end of March, so school libraries can obtain these books with aid in funding.

Kristy Inamasu teaches kindergarten at Kalihi Uka Elementary School, Hawai’i, recently winning a Milken Educator Award. Inamasu says she wants to have her students physically flipping through books, rather than being on their devices.

“Sometimes they come to us not having much experience with books, so we're really laying the foundation with that and just getting them excited about reading,” she says.

Inamasu is also intentional about what she reads with her students, trying to pick books that students can see themselves in.

“I think that's one of the main goals during our read aloud is to help students identify with characters and find value in being able to learn from characters,” she says. “We can see how characters evolve throughout a story, how their thoughts, actions, and feelings influence their decisions, and help students to make connections that way.”

Catherine Campbell, a literary interventionist in St Albans, Vermont, says engaging students is traditionally rooted in physical books. Campbell’s library hosts literacy nights, where families can come into the library and read with their children. At one, they managed to provide enough books, bought from grant money, to give out at the end of the evening.

“Everybody who came to the literacy night went home with a book or two that they didn't have to bring back, and that's pretty cool,” Campbell says. “Another thing that we've changed recently is reducing the limit of books the students are allowed to take out of our library.”

She says this has kept them reading on their own and with their families at home – and, so far, they’ve had no issues with returning books to the library on time.

Reading as Entertainment

Over the course of her career, Campbell says she’s seen a decreased interest in reading in favor of technology.

“When you would ask what they did over the weekend, they used to say, ‘Oh, I went sledding or, I played outside and built a snowman,’” she says. “Nowadays it's ‘Well, I played on my PlayStation or my Xbox.’”

It’s hard to compete with technology, but Campbell continues to promote reading in new ways, like using technology to complement instruction or having students read books online.

“The technology is going to be there, but we have to work harder to keep their scores up by showing them that reading can also be a form of entertainment,” Campbell says.

Students with low reading engagement are more likely to read fiction on a screen, compared to their high engagement peers, according to the National Literacy Trust. Campbell tries to tap into that trend to boost reading.

Programs like Amplify or Boost allow students to select books of interest and can also make accommodations for students, such as reading to the students and giving them access to more books at home.

“Some of them don't have books that they can actually read at home, but they do have technology, so I encourage them to get their reading done through an online program at home,” Campbell says.

Every night, Campbell’s students are supposed to log 15 minutes of reading time, signed by their parents. When one of her students wasn’t turning in her signed log, Catherine asked why she wasn’t reading.

“[I asked], ‘What's going on with not being able to get this done?’” Campbell says. “And she said --- she was very honest --- ‘No, I’d just rather play Fortnite.’”

Her student didn’t have books that she could read at home by herself, so she offered to lend out some books the student had read in the year before.

“She got really excited, because it didn't feel like such a daunting task for someone who reading was already a struggle, because they were familiar texts,” Campbell says.

The Interaction of Reading

Inamasu’s classroom has a daily Read Aloud with her students, where Inamasu will read a story out loud to her students. They read the book multiple times, each time with a different purpose, such as just enjoyment or seeing how a character can grow. When students read on their own or take a book home, they often reach for one the class reads together.

“They're learning how to read, so it's giving them the confidence to read those words. It helps them to make connections, because they've already heard it, and helps them be more confident as a reader,” she says

When students talk about books with their families, teachers and friends, it helps develop their reading and comprehension skills, Inamasu says.

“Yes, the focus is on teaching students how to read, and that's what we want them to be able to do and hope to come out of those lower grades with,” she says. “But at the same time, the bigger purpose of reading is to make meaning and to make sense of things.”

The easiest way to get kids engaged in reading is to get the family involved as early as possible, she believes.

“We've done some literacy nights here where families and caregivers come in with their kiddos and there's a read aloud, and sometimes there's a craft or a game or something that's connected to the story that was read,” she says. “And I think that modeling is really important to show kids how much fun reading can actually be.”

Hoyle Walkama’s “Reading Raffle” has her students interact with their books by asking their opinions.

“I tell them, if you didn't like it, that's absolutely fine,” Hoyle Walkama says. “So they have to tell me, ‘I thought the book was good or I thought it was bad.’ One little girl said to me, ‘I like the people in the book, but I didn't like the way the book was written.’ I mean, that’s an opinion. Kids need to give their own opinion, not have an adult give them an opinion.

She chooses her books and activities based on relevant holidays to build interaction. For example, her students created patches for a patchwork quilt that reflects the one on the Underground Railroad after reading a book discussing it for Black History Month.

“The learning isn't just in the reading corner,” Hoyle Walkama says. “It continues on.”