What are you most proud of?”

When Tricia Brown’s principal asked her this question last year, that was her opportunity to discuss her most significant accomplishment: Cultivating connection and safety among her second graders—all English language learners with little to no verbal expression.

Brown could have mentioned her use of microlabs (small breakout groups) that enabled her students to practice conversation and active listening. She might have underscored her efforts to build a strong sense of community, so her students could be physically and emotionally ready to pay attention, absorb information, and engage with others.

Instead, her eyes filled with tears. ”I cried because what I was most proud of was so elusive to describe or measure,” remembers Brown, who teaches elementary school, in Lawrence, N.Y. “I felt like, ‘That’s all I did? I had so much more to do.’”

If unchecked, this feeling of always wanting to do more can spiral into teacher guilt.

This feeling of not doing enough for students is common among educators. Learning how to redirect it is critical to fostering a healthier mindset, increasing job satisfaction, and creating a more positive learning environment for the entire school community.

What is Teacher Guilt?

Teacher guilt differs from compassion fatigue, where educators absorb their students’ trauma to the point of emotional or physical exhaustion, and from toxic positivity, which trivializes a person’s pain.

Teacher guilt can include feeling badly about behaviors such as taking sick days, leaving on time at the end of the workday, or not grading student assignments at home.

For many educators, guilt surfaces from the dichotomy of wanting to do all you can for your students and school community, while simultaneously feeling overwhelmed by a lack of support, according to NEA’s Crystal Foxx, whose work focuses on health and mental wellbeing for students and educators.

“We have teachers who are not only covering their own classes, but also giving up their lunch and planning periods to cover for others,” Foxx explains. “When you’re facing nearly double the workload and can’t complete everything you’d like to, it leads to feelings of guilt.”

She adds: “The onus is not on educators, but on policymakers and politicians who perpetuate a system that creates this cycle of guilt, as it’s not possible for one person to get everything done without sacrificing something, such as family or personal time.”

The Heavy Burden of Underfunding

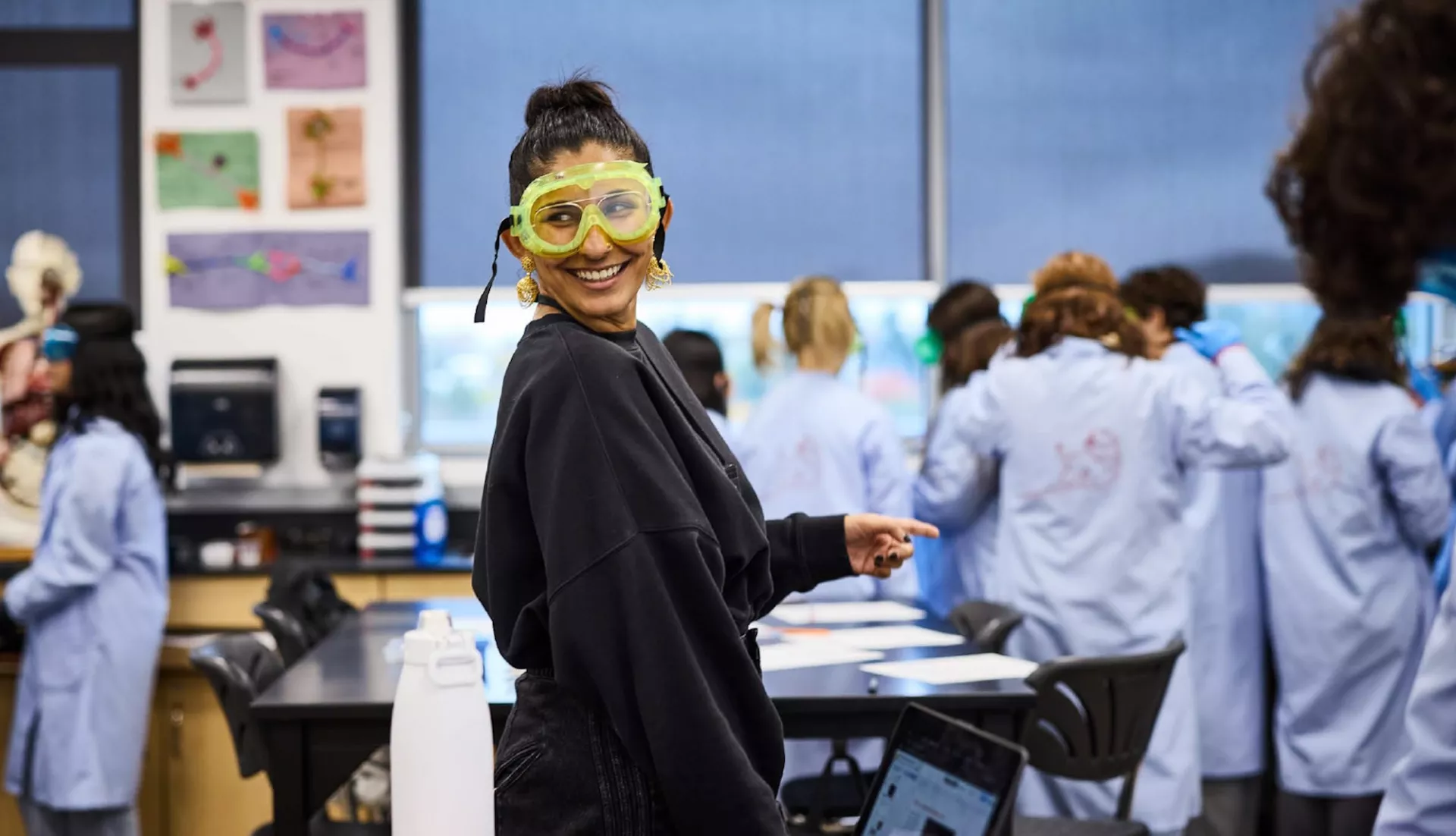

Darshanpreet Gill’s early years as a science teacher were marked with a steep learning curve. “I didn’t understand how school funding worked,” Gill explains, reflecting on her initial two years as a teacher in California. “I bought everything for my classroom because I thought that was just what you did.”

Nearly 95 percent of teachers spend their own money on school supplies and other items students need to succeed, averaging about $500 per year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But educators face other challenges as well.

It’s especially problematic when schools lack the resources to support students who arrive at school hungry or bring in difficulties from home.

“What you are given in terms of resources and what you’re expected to do are never aligned,” says Gill, who now teaches science at a career and technical school in Portland, Ore. “This literally feels terrible on your body, because you want to do the right thing for your students, but you have to come to a point where you say: ‘I can’t do everything, but I should do what I can, and then I have to leave it here.’”

Let Go of the Guilt

Today, Gill recognizes that elected officials are mainly responsible for underfunding schools. “We elect them to represent our best interests, and they should fulfill that responsibility,” she says.

In 2023, when school officials fell short of this responsibility, Gill joined the Portland Association of Teachers in striking with thousands of her peers. Together, they advocated for changes that improved working conditions and student learning environments.

Their efforts secured a collective bargaining agreement that includes more planning time, limits the amount of time educators spend on standardized testing, and expands mental health resources.

Brandy Bixler, a former teacher who is now an NEA trainer on social and emotional learning, advises: “Think about your emotions as a guide to your actions and what you have control over.”

She explains: “Anger can be a useful emotion if, for example, you see your superintendent getting a new office with a custom-built desk, while your class goes without textbooks. Anger can empower you to take action, but guilt over not being able to buy your students winter clothes isn’t helpful—so let go of that guilt.”

Instead, she suggests channeling your anger into something that makes you feel powerful, like voting for pro-public education candidates and attending school board meetings to address underfunded schools.

‘Create Boundaries and Joy’

While Gill and Brown understand that district funds should be allocated to ensure schools are fully staffed and properly resourced, they do what they can to help students during school hours—and then reset at night for the next day.

“I made a decision to create joy in my classroom because without it, it would be too heartbreaking,” says Brown, who finds comfort in creative outlets like knitting, gardening, cooking, and walking her dog— all of which give her a rest and provide space from the pressure and pace of teaching.

Gill grounds herself in her purpose as an educator—and a good one too.

“I’m proud of the work I do, … which is why I fight for it,” she says, outlining some of her mental checkpoints: Trusting herself as a competent teacher; saying yes to what benefits students; and sticking to her contracted hours.

“This keeps me available to the kids,” Gill explains. “It also lets me work out in the morning and care for myself. We’re full people, and waiting for society to approve of your humanity won’t happen.”

This mindset, she adds, “benefits systems that make you think your worth is tied to productivity, which isn’t true.”

Instead, she suggests: “Create boundaries and joy without feeling like you must earn your rest or time off.”

5 Ways to Build Resilience in the Classroom

NEA’s Brandy Bixler, who provides training in social and emotional learning, offers the following tips:

1. Seek mentorship: This helps to build community and support for students as well as among teachers at different career stages. Speak with your administrators to help pair you with a mentor.

2. Manage emotions: Use cognitive behavioral strategies to process emotions in a constructive way. Therapy is a good tool to help change thinking patterns and behaviors

3. Break isolation: Connect with colleagues to combat feelings of isolation. Collaborate on lesson plans or simply check in with a colleague.

4. Community responsibility: Understand that addressing educational challenges is a collective effort, not only the responsibility of individual teachers. Find out what others may know. A social worker may be able to connect a student’s family with a food bank or shelter.

5. Recognize the journey: Acknowledge that teaching involves both challenges and successes, and it’s important to celebrate progress.