Key Takeaways

- Many school districts are still struggling with staff shortages and more educators are feeling burned out and demoralized.

- Higher pay always helps with teacher retention, but improving working conditions—student behavior especially—has moved to the forefront of educators’ concerns.

- Lawmakers have not done enough to alleviate the crushing workload and undue stress that is pushing too many teachers out of the profession. Educators and their unions are working to change that.

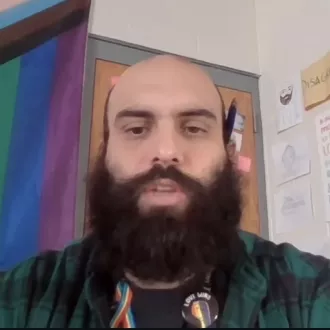

Joe Holloway remembers when, not too long ago, public school educators were regarded as heroes.

“During COVID, we were educating our students under very stressful circumstances,” says Holloway, who teaches social studies in East Hampton, Conn. “We were frontline workers. We didn’t get big pay raises, but we had, and have, a love of teaching. And everyone seemed to be very positive about what we were doing. But it was more of a glimmer of positivity.”

Soon after in-person learning resumed, the national conversation around schools and educators turned bleak, polluted by “culture war” propaganda and anti-public education rhetoric that has only intensified over the past few months. School districts have been destabilized by severe staff shortages and more educators are considered leaving.

Meanwhile, says Holloway, “more and more has been asked of us. it doesn't seem to stop.”

Higher salaries will always be a top priority, but better pay can't completely reduce the elevated levels of stress and anxiety that has plagued the teaching profession over the past decade, if not longer. The pressure of the job and the impact it has been having on educators and students hasn’t been adequately acknowledged, let alone addressed.

That's why Holloway joined other members of the Connecticut Education Association (CEA) and elected officials at a press conference last November to spotlight educator burnout. They urged state lawmakers to step up and allocate sufficient funding to mitigate the factors that are pushing educators to exhaustion, hopelessness, and an early exit from the profession.

“Teaching has become mentally, emotionally and physically exhausting,” says Elsa Batista, a world language teacher in Newington, Conn., who also spoke to reporters. “We are strong, resilient, and creative, but we need support, we need help in our classrooms. Right now, that’s not happening, and we cannot afford to lose more teachers.”

A Major Public Health Challenge

In 2025, researchers at the University of Missouri released a study in which they surveyed around 500 public school teachers. They found that 78 percent have thought about quitting their profession since the pandemic. The reasons? A lack of administrative support, excessive workloads, inadequate compensation, and challenging student behaviors.

The authors called stress and burnout a “major public health challenge confronting the education system as teachers are essential individuals supporting children and youth in their formative years."

A continued failure to understand the factors that lead to high teacher turnover, such as teacher stress and burnout, is creating a ripple effect, explains Wendy Reinke, a University of Missouri professor in school psychology and co-author of study.

“If teachers struggle, instruction suffers, and students don’t learn as they should,” Reinke explains. ”When there aren’t enough teachers, schools may hire uncertified staff or increase class sizes, making effective instruction and learning less likely. Disruptive behavior also spreads—kids in disorderly classrooms carry those habits into the next grade.”

“Burnout” has become a ubiquitous term, but it's likely not the most accurate word to describe what educators have been enduring. (Doris Santoro, professor of education at Bodoiwn College prefers “demoralization.”) “Burnout” can imply some sort of weakness or deficit on the part of the individual educator and an inability to cope—a form of victim-blaming. This point of view can lead to an abundant supply of unhelpful self-help strategies.

For many educators, using the most precise word isn't as important as understanding the root causes.

Burnout is a systemic problem, and the burden is not on the individual educator to prove they can navigate through the enormous pressure placed on them, says Kim Kneller, a science teacher in Allentown, Penn. "People should take care of themselves, but you can't just yoga, breathe, and self-care yourself out of burnout."

Kneller, who in 2024 wrote her doctoral dissertation on teacher burnout, says the focus should be on the workplace. “The people that dictate what our daily lives look like—that’s where there needs to be more awareness and accountability.”

‘Just One More Thing Added to our Plate’

In November 2024, CEA released a survey of its members on the challenges they face in schools. Specifically, they were asked to name five primary concerns. Stress and burnout topped the list. Asked what the main causes of burnout were, educators cited challenges with student/discipline first, followed by insufficient pay, lack of respect, politicians and non-educators making decisions that affect education, and too many district initiatives.

“We want to work with all stakeholders on these issues,” Joe Holloway says. “But teachers having more say in curriculum is a big sign of respect. The fact that politicians are making these decisions is preposterous.”

The rising dissatisfaction over these and other working conditions (also cited in the University of Missouri study and other surveys) suggest that pay increases alone are unlikely to bring about large shifts in teachers' well-being or intentions to leave the profession.

“I think [working conditions] are probably everyone's number one,” says Kneller. “Everyone I know that has left has not left because of money. They've left because of something that happened to them in their place of work. They just put a boundary down, or they felt like they were mistreated. It could be the constantly changing expectations.”

Not only has the workload increased exponentially, so has micromanagement, says Nicholas Cream, a social studies teacher in Holyoke, Mass.

“It’s always just one more thing added to our plate. And when it comes to our classrooms, we're not really trusted to do what we know will work for our students" Cream says. “If you don't have every single minute of your class planned out, it is seen as a problem."

Cream, who is also president of the Holyoke Teachers Association, says it sometimes feels like teachers are being “pushed out, not burned out.”

And when schools adopt new technologies to ostensibly help educators do their jobs, the results can backfire. A 2024 study by Auburn University found that if new learning platforms such as Canvas or Schoology were introduced without removing old requirements, teachers reported higher levels of burnout. “Instead of being used to replace old ways of completing tasks, the learning management systems were simply another thing on teachers’ plates,” the researchers reported.

As more tasks and responsibilities are added, the profession has been transformed—and not for the better, says Becky Bissegger, an elementary school teacher in Salt Lake City.

“School isn’t fun. By that, I mean engaging for students and rewarding for educators. It’s the opposite. It’s like boot camp for a lot of students.” Bissegger says.

The toxic political climate and attacks on public education that have intensified in recent months have only exacerbated an already tense and trying environment.

“Teachers feel that there’s an anti-public ed sentiment out there,” Janet Sanders, a teacher in Herriman, UT told reporters in January. “It feels like we're being persecuted... We just feel threatened, and we feel for our students because we know that they will not be well served.”

The Challenges Over Student Behavior

Since the pandemic, behavioral challenges in the classroom have been on the rise in terms of frequency and severity, and schools have largely been ill-equipped to manage it.

“Our students are coming into school every day with greater needs in every aspect of their lives, including around their mental health. But the support just isn’t there to help teachers and staff,” said Bissegger.

Mirroring the finding in the CEA member survey, a 2024 survey by the RAND Corporation (funded in part by the National Education Association) revealed that student behavior was cited by 44 percent of teachers as the top-source of job-related stress.

“That doesn’t surprise me,” says Nicholas Cream. “COVID changed a lot. With everything students bring into the space, you just cannot know how things are going hit or how hard a day is going to be.”

Cream also suspects that the ongoing struggle over cellphones in the classroom has helped push behavioral concerns to the forefront of job stressors.

“We’re all dealing with it. Students are addicted to these devices. But we’re told we’re the ones who must enforce the rules. Again, it all accumulates. We’re all being weighed down by this daily work that has little to do with real teaching,” Cream explains.

According to a 2023 Pew survey, 72 percent of high school teachers report cellphones are a major distraction in the classroom—even when there are cellphone restrictions in place. A 2024 National Education Association (NEA) poll found that 90 percent of teachers support prohibiting student cellphone use during instructional hours. Seventy-five percent favor extending restrictions to the entire school day.

Changing the Narrative

Educators nationwide have voiced their support for clear and enforceable cell phone policies and, through their union, have successfully pushed districts to act. On other working conditions issues, including class size and more planning time, collective bargaining has proven time and time again to be an effective tool for educators.

In 2024, the Massachusetts Teachers’ Association (MTA) was instrumental in a successful statewide ballot initiative in which voters decided to end the use of MCAS, a high-stakes standardized test, as a requirement for graduation. MTA President Max Page said lifting the graduation requirement will help improve working conditions by giving teachers more freedom in the classroom. “This creativity attracts students to the teaching profession and encourages them to stay,” he said.

Quote byNicholas Cream , President of the Holyoke Teachers Association

Addressing the conditions that force too many educators to exit the profession is also the responsibility of lawmakers, who can prioritize long-term funding for public schools, along with the policies that Joe Holloway says, “can revitalize respect for this profession.”

In January, on the eve of the new legislative session, the Utah Education Association (UEA) presented its own member survey of top educator concerns. “The results are clear,” said UEA President Renée Pinkney. “Educators are calling on lawmakers to prioritize funding for long-term staffing solutions; reduce stress and burnout and provide behavioral health resources.”

Changing the conversation about burnout to focus on the systemic, rather than individual, solutions is a positive first step, says Cream, especially in a treacherous political climate.

“I do think the narrative is changing, but we’re still losing educators... We have people here that are really committed to their communities and to the young people that they serve. But we want to feel like we are trusted and cared about and given the tools and resources we need to succeed.”