Key Takeaways

- About one-third of teachers nationally teach in one of the 18 states that have passed laws restricting instruction around so-called "divisive concepts," such as race, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

- Many teachers subject to state and local regulations are going beyond what the laws require, and cite concerns over losing their job as the top reason for doing so, according to new survey results from the RAND Corporation.

- A "spillover effect" is being seen in states with no censorship laws. Educators, fearful over reprisals from community members and a lack of support from school leaders, are deciding on their own to limit instruction in their classroom.

65%

55%

Since January 2021,18 states have passed laws that restrict how so-called “divisive” subjects, such as racism and LGBTQ+ issues, can be addressed in the classroom, in effect imposing gag orders on classroom teachers.

But the impact of these measures is not confined to school districts in these states. The laws, and the “culture war” political climate that produced them, have a far greater reach.

For educators not subject to state restrictions, the mere possibility that they could, for example, be targeted for harassment by a segment of the public or scrutinized by the administration is enough to compel them to decide on their own to curb discussion about certain political and social topics. Passed by right-wing lawmakers, many of these state laws are vaguely worded, leaving many educators unsure about what is and is not prohibited.

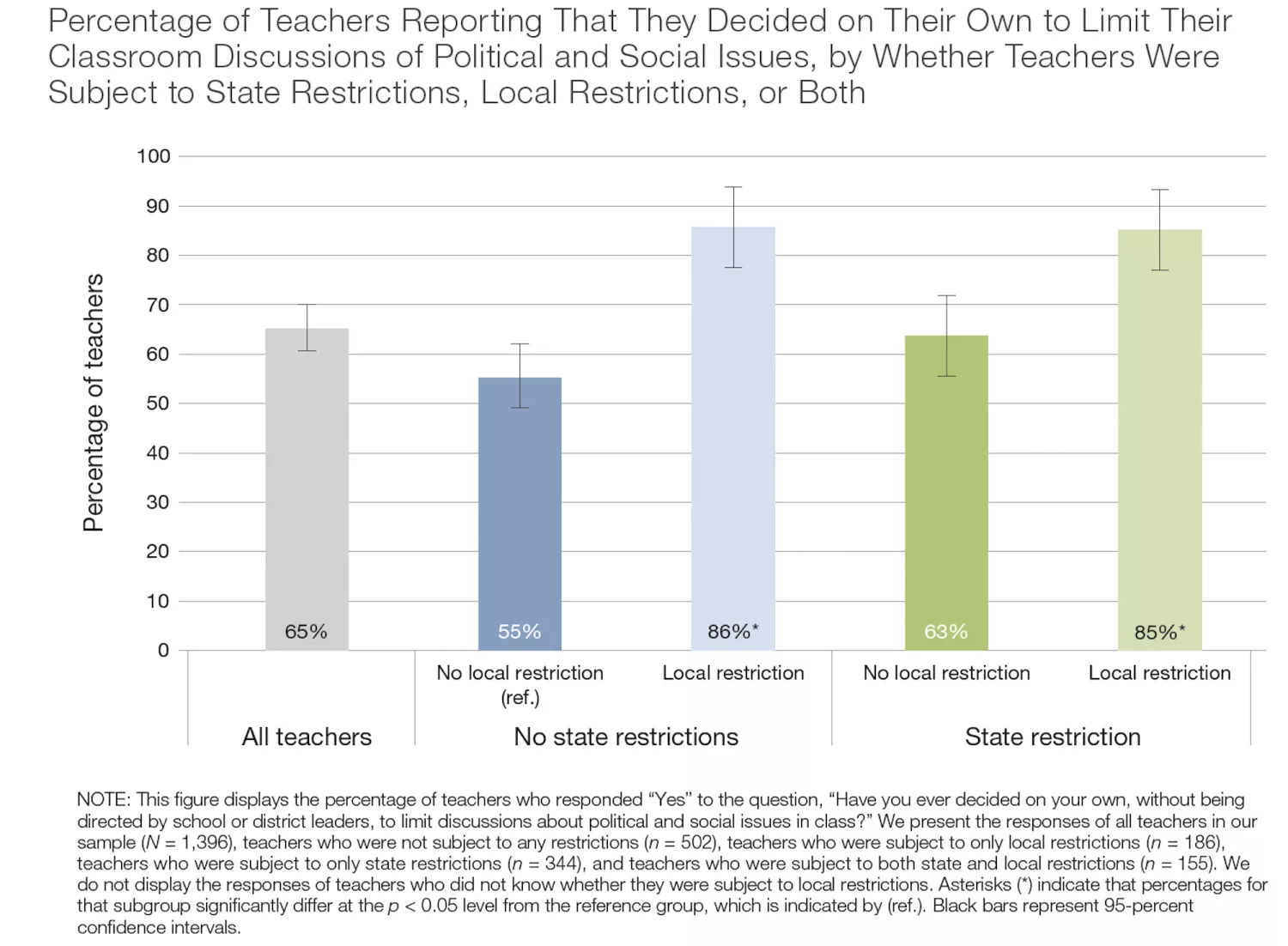

Two-thirds of U.S. public school teachers are choosing on their own to limit what they teach, according to a new study by the RAND Corporation. Furthermore, 55 percent of teachers who do not work under any state or local regulation have chosen to limit instruction. This trend is evident even in school communities where parents support classroom discussions about these issues.

That many educators have made the choice to essentially self-censor is sobering, if not necessarily surprising, news. This campaign of censorship and intimidation affects educators and students in every state across the country.

“We expected that a large number of teachers are taking this step in those states that enacted restrictions,” says Ashley Woo, RAND researcher and lead author of the new report. “But when you look at the teachers deciding to do this on their own with no state or local restrictions—and where community support is high—the numbers are surprisingly very high.”

The “Spillover Effect”

The report’s data was collected from the 2023 State of the American Teacher Survey, a nationally representative survey of 1,439 K–12 teachers (funded in part by the National Education Association) and administered in January and February 2023.

Analyzing the responses, RAND researchers identified trends relating to how teachers reacted and adjusted their instruction to state-wide laws and how they—and those teachers who were not subject to these restrictions— acted on their own. The impact of these state policies have "begun to spill over into states and localities where no such policies are in place," the researchers wrote.

This spillover occurs in two ways.

Local school systems may have adopted restrictive new policies—a directive from school or district leaders to limit classroom discussions of political and social issues—creating similar conditions in those districts under statewide restrictions. A teacher may also have decided to avoid controversial topics altogether, expanding the scope of that “no-go” zone.

“Local restrictions might have an even stronger connection than state restrictions to teachers’ decisions about whether and how to discuss political and social topics in class.”

— RAND Corporation

“These teachers are going beyond whatever their school district leaders had said to them. So they are making those additional decisions about what to discuss in class on their own,” Woo explains.

Not surprisingly, the decision to self-censor was more prevalent in more politically conservative communities, regardless of any state or local restriction. Still, 40 percent of teachers who worked in more liberal communities and were not subject to any restrictions decided to limit what they addressed in class.

According to the survey, teachers' decisions were more likely to be influenced by local restrictions over state ones. More than 80 percent of teachers subject to local restrictions decided on their own to curb classroom discussions, regardless of the presence of state restrictions. Teachers who were subject to only local restrictions were more likely than teachers subject to state restrictions to decide on their own to limit discussions by a margin of 86 percent to 63 percent.

Local leaders, Woo explains, are more ideally situated than state lawmakers to scrutinize teachers’ choices and enforce compliance. In addition, teachers might place more weight on the directives of their local leaders.

“Locally enacted policies might reinforce (or push against) state policies,” the RAND researchers write. “Taken together, the state and local policies to which a teacher is subject create a specific teaching environment, which has consequences for whether teachers feel supported to engage in instruction about political and social topics.”

A Lack of Support

Many educators said they were not sure if their school or district leaders would support them if parents complained. Forty-nine percent of teachers not subject to state or local regulations said that it was the top reason why they chose to limit instruction. They also cited a lack of guidance from local leaders on how to address political and social issues in the classroom.

Forty-four percent of teachers subject to state and local regulations cited a fear of losing their job as the number one reason they decided to limit their instruction.

Support from the administration is a key working condition that, along with professional pay, is a driver in many teachers’ decision to stay or exit the profession. If educators don’t feel supported as they fend off attacks from community members and politicians, school districts will find it even harder to keep teachers in the classroom and recruit new ones.

In an earlier survey that looked at educator well-being, RAND found that 40 percent of teachers said the political tension around certain classroom topics was a source of job-related stress.

“It’s the anxiety of having to deal with conflicts with some parents or others in the community,” explains Woo. “Or this climate makes more work for them because they have to go look for other materials. It all adds up.”

‘The Midst of this Craziness’

Despite the concern many educators have about the community protests over what is taught or read aloud in class, most parents strongly support public schools and oppose book bans and laws censoring classroom instruction. While the voices demanding censorship are loud and well-organized, they are still a minority.

But the “culture war” on public schools continues to sow division and undermine confidence in U.S. public education. As PEN America has documented, state lawmakers are also pushing what it calls “educational intimidation bills”—legislation that does not explicitly impose classroom censorship or specific book bans, but contains enough murky, menacing language to paralyze district officials and educators. The goal is to open the door wider for politicians and outside groups to further interfere in classrooms— “threatening the freedoms to teach and learn with death by a thousand cuts.”

“There’s a lot of silent censorship happening,” Mari Butler-Abry, a school librarian in Iowa recently told NEA Today. “My school district has tried really hard to preserve students’ rights in the midst of this craziness, but others have erred on the side of caution and taken out way more than they should have. And their explanation is that ‘we don’t know.’”

Last December, thanks to a lawsuit filed by the Iowa State Education Association and others, an Iowa state law that sought to ban books from schools and to bar classroom discussion of gender identity and sexuality for students below the seventh grade was blocked by a federal judge. The law, he said, was “incredibly broad” and “unlikely to satisfy the First Amendment under any standard of scrutiny.”

In February, the Georgia Association of Educators, in the first federal lawsuit challenging classroom censorship policies in the state, sued the Cobb County School District. The lawsuit alleges that the district’s policies on “divisive concepts” are in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

One of the plaintiffs in the case is Katie Rinderle, a fifth-grade teacher who in 2023 was terminated for reading My Shadow is Purple, an age-appropriate book about self-acceptance and gender identity, to her class. The lawsuit seeks to block the enforcement of the district’s censorship policies and calls for Rinderle’s reinstatement.

“The school board’s decision to fire me undermines students’ freedom to learn and teachers’ ability to teach,” Rinderle said. “Many CCSD educator are committed to creating inclusive, diverse and empowering environments free from discrimination and harm, ensuring LGBTQ+ students feel safe, affirmed, and centered in their learning journey because that is what our children deserve.”