Key Takeaways

- The New Hampshire state law had resulted in teachers self-censoring their lessons of any reference to race or gender, afraid to cross an invisible line in their classrooms.

- They didn't know what they could or couldn't say. In a big victory for teachers, a federal judge ruled that the law’s vagueness was unconstitutional.

- If teachers had violated the law, they could lose their state licenses and essentially their careers. Younger teachers especially didn't want to take the risk—but students ended up paying the price.

Next year, New Hampshire teacher Patrick Keefe is putting Toni Morrison’s Beloved back into the hands of his AP English Literature students.

Since his union, NEA-New Hampshire, won its lawsuit last week, overturning their state’s “banned concepts” law, Keefe and his colleagues can teach the lessons that they know lead to critical thinking and student learning. They can include novels with Black people, such as Beloved, without fear that a classroom discussion will end their teaching careers. The judge’s ruling brings huge relief to New Hampshire educators who have been teaching in fear since the law passed in 2021.

“It’s a great victory, absolutely!” says Keefe. “I haven’t done Beloved in two years, and I know I’ll do it in AP next year. I’ll probably do To Kill a Mockingbird too, with my ninth graders—and I won’t have to worry about being brought before some kind of rigged panel!”

With its focus on “banned concepts,” the law limited New Hampshire educators from talking or teaching about race and racism, gender, sexual orientation, and disabilities, but it was never clear to educators what exactly they could or couldn’t say. The law was like an invisible line in their classroom. Because they didn’t know where it was, teachers self-censored, trimming their lessons of anything to do with race or gender. Meanwhile, the penalties for violating the law were crystal: Teachers found in violation could lose their state license.

In his ruling, U.S. District Judge Paul Barbaro pointed to the vagueness of the law, calling it a “sword of Damocles” that hung over educators’ heads, and deemed it unconstitutional. People who are subject to a law “should be given a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited,” he noted. In parts of this law, “the text provides no clues,” he wrote.

“I didn’t know what I was supposed or not supposed to say, but I did know that if I screwed it up, it could mean my teaching license, my career, my livelihood, my ability to pay the mortgage,” says Jen Given, who was teaching AP World History in southern New Hampshire when the law passed.

Educators also faced likely lawsuits by parents, the judge noted.

The lawsuit filed by NEA-New Hampshire and its partners, including the American Civil Liberties Union of New Hampshire, is one of many in recent years. NEA affiliates in Iowa, Georgia, and Florida have filed similar lawsuits against similar laws. In Iowa, a federal judge issued an injunction in December, temporarily blocking the law, thanks to a suit filed by the Iowa State Education Association (ISEA) with parents and publishers.

The Lesson that Got Mrs. O’Brien in Trouble

In New Hampshire, teachers say that it wasn’t just history that was suppressed by the law. It was good teaching.

In his ruling, the judge agreed, noting how the law made it hard for teachers to “ask pointed questions or encourage debate,” or, in other words, “encourage the development of critical thinking skills.”

Indeed, the lesson that got high school social studies teacher Alison O’Brien yanked out of her classroom and escorted into her principal’s office is one of her best. Around the same time that she learned a state investigator was looking into it, one of her tenth graders walked up to her at an afternoon play rehearsal and said, “Mrs. O’Brien, that was an awesome class! I totally understand the impact of the Harlem Renaissance!”

In 90 minutes, O’Brien pivots from Reconstruction, Jim Crow, Southern lynching, and the Great Migration of African Americans to northern cities to the Harlem Renaissance. Poetry from Langston Hughes and Paul Lawrence Dunbar is read. Music from Count Basie and Louie Armstrong is played. The big question: “Why art?

“Black Americans are escaping great violence in the South,” O’Brien notes. “Why art? Why not politics? Or speeches?” Toward the end of the lesson, in direct compliance with New Hampshire’s social studies standards, which say students should understand the “continuity of history,” O’Brien plays portions of contemporary music videos, including the ending of Beyoncé’s Formation, which shows a child dancing in front of SWAT officers. A painted message says, “Please stop shooting us.”

“I always say to the kids, we’re not talking about whether we agree or disagree with these artists, we’re talking about ‘why art’ and what they’re trying to accomplish. And do we see the continuity of history from the Harlem Renaissance?” she says.

“At no point was I telling kids what they should believe,” says O’Brien. “I’m not even saying what the artists believe. I’m asking. I’m providing information. I’m focusing on inquiry-based learning and building their critical-thinking and analysis skills.”

Quote byAlison O'Brien , Social studies teacher

Banned: Good Teaching

The best teaching is engaging. It’s interesting. And it forces students to think for themselves. When Keefe taught the Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved, he asked them to consider the story “in a contemporary framework.” The main character, Sethe, is a former enslaved person whose actions stem from the trauma of slavery. Do students today see a lasting impact of slavery?

[Under the “banned concepts” law], “if I brought up George Floyd or any other incident involving race in contemporary society, it’d be tricky. Actually, it’d be more than tricky,” says Keefe. “I could be called down to the principal, brought before a board, and my license [revoked].” So, he chose not to play devil’s advocate in a lesson about Beloved, or use the Socratic method to draw out analytical thinking.

“When the federal judge overturned [the law], I was more than thrilled,” says Keefe. “It was like I can actually teach!”

Similarly, in her court deposition, Given told the judge she stopped asking open-ended questions in assessments, “out of concern that…students [might] believe they had to agree with a certain position to score well.” She also disallowed them to choose their own research topics out of fear that “the students would include subject matter in their papers that could violate the [law.]”

Even worse, Given stopped asking students to consider their own experiences and interests in the context of historical events and trends, even though she knew it would help them learn. “Given found that these changes negatively impacted student learning and resulted in decreased class participation,” the judge wrote.

O’Brien, on the other hand, didn’t change the way she teaches, she says. “My view has always been that if I can’t teach history accurately, I don’t want to teach history. All I did was provide students with information and ask them questions about it, relating to state standards. If I can’t do that, then I don’t want to do this.”

Eventually, the state “investigation” into her lesson amounted to nothing much, but the episode did impact her colleagues. “When other teachers in my building heard what happened to me, it did change the way they teach,” says O’Brien. “And I feel that was the intent. They wanted us to be scared.”

That fear especially affected new teachers, which Given noticed, too. As a local union leader representing new teachers without tenure, Given saw her newer colleagues “were truly terrified,” she says.

“They’ve got hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loans. They’re making $30K a year. And it’s their first year in the career that they’ve chosen. They can’t afford to rock the boat,” she says. “But what that means is the kids in front of them are not being educated appropriately. You could have a kid of color who is hearing none of their history or stories.”

Diverse books and lessons are mirrors for kids of color, validating their experiences and making them feel seen and valued. They’re helpful to white students, too, who also must live and succeed in a multicultural, interdependent world.

“When access to these titles is lost, our students lose the opportunity to build empathy toward others who might not look, or live, like them. Every student deserves to see themselves in the books they read. It is how they learn that their stories and their lives matter,” wrote NEA President Becky Pringle, with authors Caroline Tung Richmond and Ellen Oh, in an op-ed published last year in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Efforts by some politicians to ban these kinds of texts and lessons are really efforts to divide parents and educators, and make it easier for those politicians to divert money out of public schools, NEA leaders say.

It's Not Just New Hampshire

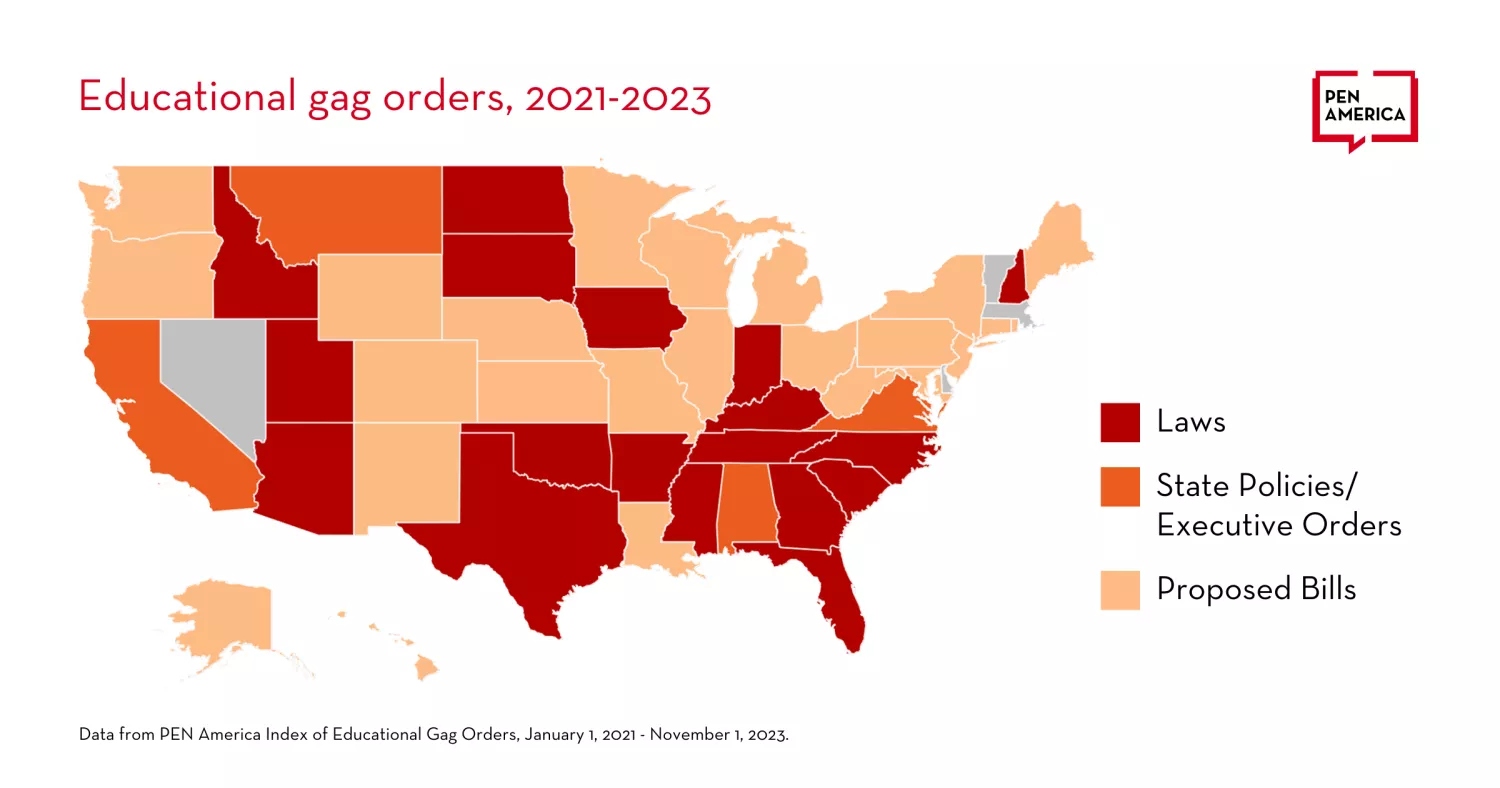

The New Hampshire law is one of many across the U.S. modeled on an executive order by former President Trump who banned “divisive concepts” like diversity and equality from federal trainings. While that order was revoked by President Biden, 36 states—including Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Tennessee—have introduced more than 130 bills to restrict educators from talking about race and racism, and LGBTQ+ people, according to PEN America, which tracks the legislation.

In Georgia, a trio of vaguely worded “divisive concepts” laws led to teacher Katie Rinderle getting fired last year, after she read aloud a picture book that she bought at her school’s Scholastic book fair. In South Carolina, high school teacher Mary Wood was reprimanded for teaching a lesson on race, using a non-fiction book by Ta-Nehisi Coates about what it’s like for him to grow up Black in America.

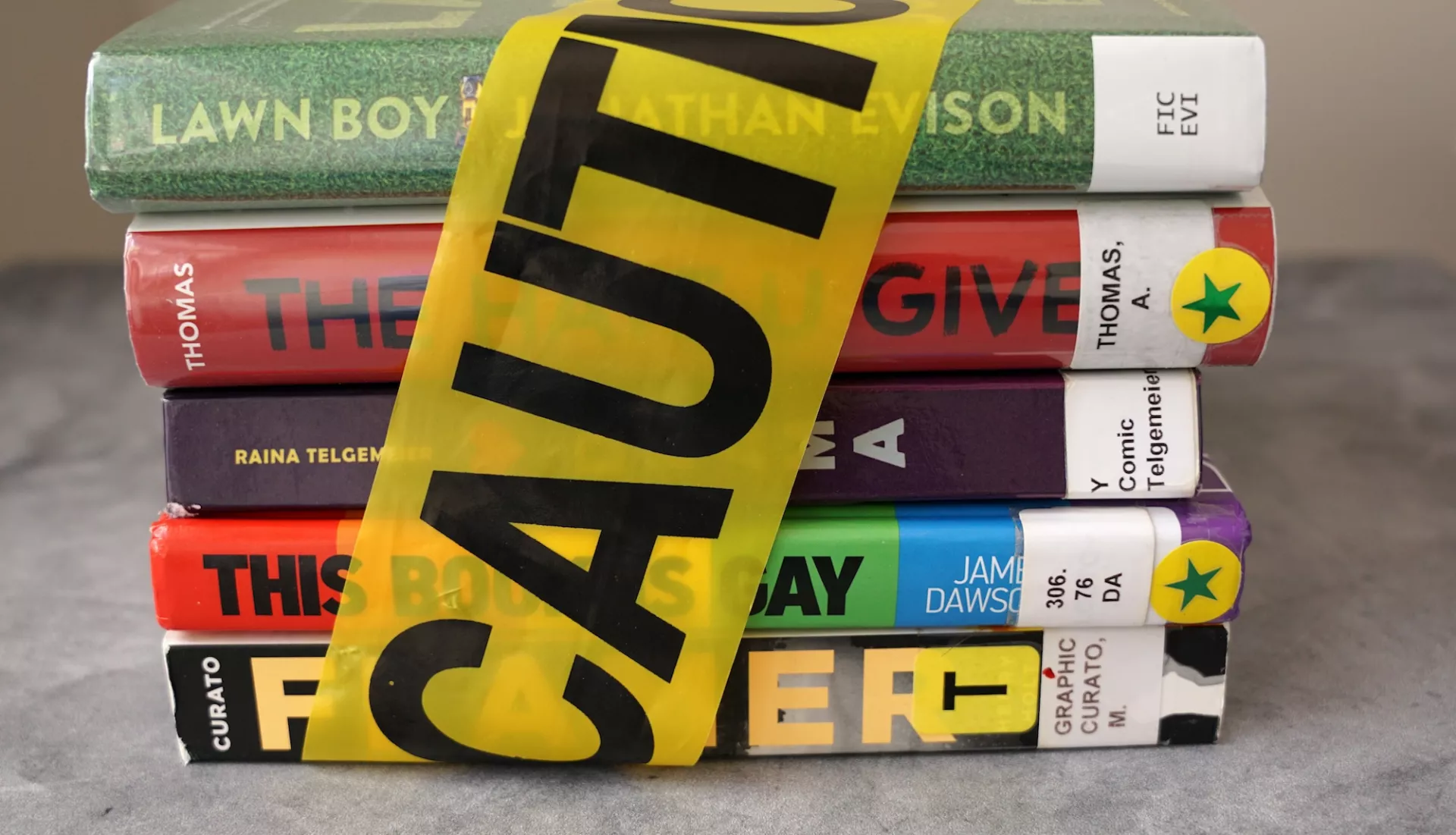

“I heard we can’t learn about Black people this year,” one student told an Iowa teacher last year, as a new law caused books to be pulled from Iowa classroom and library shelves. Those included classic novels like 1984 by George Orwell, As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, plus a children’s biography of U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, who is gay.

Also yanked? The Holocaust memoir Maus by Art Spiegelmen; Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak about surviving sexual assault; and George Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir that describes his experience with anti-gay bullying.

This is what happens when extremists take office, Pringle warns. “In 2022, extreme right organizations endorsed and funded over 500 candidates for local school boards,” she said, in the Atlanta op-ed. “While that number is small compared to the 71 percent of pro-public education candidates who won over culture war candidates, unless we rise up to challenge them, these new members will continue the practice of whitewashing our history by taking books from our students, as they march toward their ultimate goal: the destruction of our democracy.”

Educators, alongside parents, students, book publishers, and other allies, are determined not to let that happen.