Key Takeaways

- The trauma of gun violence is immeasurable and has lasting effects on individuals who and communities that are directly and indirectly affected.

- This section of the guide focuses on coping with trauma after a gun violence incident and transitioning to support communities in their longer-term needs.

- This section also addresses effective ways for association leaders, staff, and worksite leaders like building representatives and faculty liaisons to evaluate and improve the response to the incident.

Gun Violence Recovery Executive Summary

The recovery section of the NEA School Gun Violence Prevention and Response Guide focuses on coping with trauma and grief after a gun violence incident, restoring a safe and healthy learning environment, and providing support to students, educators, and those impacted by gun violence incidents as the initial response turns to longer-term needs. This section also addresses effective ways for association leaders, staff, and worksite leaders like building representatives and faculty liaisons to evaluate and improve the response to the incident. Just like following the recommendations in the preparation section will facilitate response-related work, effective preparation and response will enhance recovery efforts. For broader context, consult the other sections of this guide: Part One—Prevention, Part Two—Preparation, and Part Three—Response.

Address Primary and Secondary Trauma

Extensive research on trauma caused by gun violence indicates that it extends far beyond those killed or wounded in the incident itself. The prevalence and threat of school shootings have created a generation of young people in the United States who are growing up with a constant fear of being shot and killed in a place where they should feel safe.

The collective trauma that gun incidents elicit is remembered and recollected by community members at various times and in multiple spaces, sometimes predictably—like on anniversaries of the incident—and sometimes unpredictably—for example, when a sound or smell elicits a reaction. Both post-traumatic stress and secondary traumatic stress can result from exposure to gun violence. Those impacted by such trauma can include direct victims, students in the school where the incident took place or in other communities, first responders, community members, and educators. It is important to note that educators, who are often the on-the-ground front line responders to crises, are also at risk of compassion fatigue.

Plan and Assess Responses

The U.S. Department of Education and other federal agencies have produced guides for developing high-quality school emergency operations plans in K-12 schools and institutions of higher education (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-a); (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-b). Part Two of this guide, which focuses on preparing for incidents of gun violence, provides information on how the association can use these plans, noting that individual states and localities may employ different approaches to emergency planning. For purposes of the response section of the NEA guide, the federal government’s approach to recovery bears attention describing the four fundamental kinds of post-crisis recovery: academic recovery, physical recovery, fiscal recovery, and psychological and emotional recovery. The 2018 NEA School Crisis Guide also provides resources and strategies to help support crisis response teams in recovery efforts (NEA, 2018).

Other important elements of a recovery effort to assist victims include access to mental health services, peer support, legal help, and logistical and financial support, such as relocation costs and funeral arrangements. This section of the guide provides a variety of programs and resources available to victims, including financial and legal support and information on how to deal with post-traumatic stress and trauma.

Build Strong Partnerships

Strong partnerships with organizations working statewide or locally provide the opportunity to enhance association work related to incidents of gun violence. This section of the guide includes links to national-level organizations that may have state or local-level counterparts. Identifying local groups whether professional associations, non-governmental organizations, or academic centers may also serve the same purpose. Whether they focus on racial and social justice, countering gun violence, promoting student health, or another relevant topics, identifying and building relationships with such groups establishes mutual opportunities for support in response to the incident in the short, medium, and long term.

Develop Long-Term Media and Communications Strategies

In the days, weeks, months, and even years after the incident, it will be important to develop a longer-term media strategy, which should include when, where, and how to communicate with the media. Recognizing that the media needs a story, the designated spokesperson should provide accurate, timely information and understand the cycles of media response.

The needs of the media change as the situation evolves.

It is important for the association to develop media protocols that, for example, determine how the association will handle local versus national media, how to work with administrators on press releases, statements, and talking points, and how to handle interview requests. Throughout this process, association leaders should be assessing and reviewing the protocols, as necessary.

Assess for Improvement

The association and administrators should evaluate gun violence incident work to identify areas for improvement and evolving circumstances and/or emerging needs. Within the association, bringing together those who played a role in the work—and those who did not play role but could have—and revising protocols, approaches, and resources will lead to more effective work in the future.

Part 4: Recovery

Looking at the elements of high-quality recovery efforts including addressing trauma, assessing responses, partnership building, and communication strategies.

Find our comprehensive list of resources from NEA, Everytown for Gun Action, and other partners, including support for trauma-informed recovery and emergency operations plans.

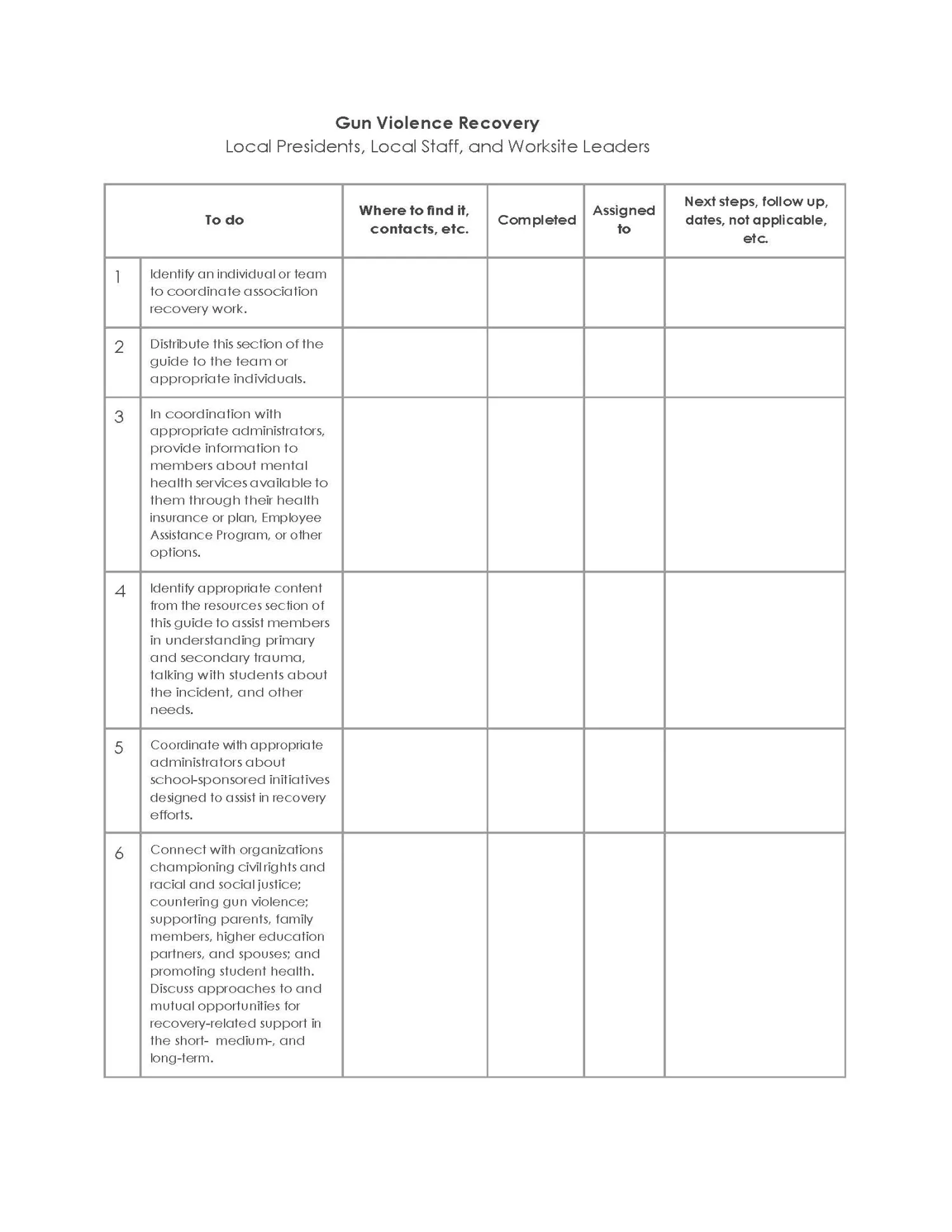

Download two checklists with strategies and action steps to take in the weeks and months following a traumatic event.

Background

The trauma and grief caused by gun violence does not end when the shooting stops. People may identify as survivors if they have witnessed acts of gun violence, experienced intimate partner violence with a firearm, been threatened with a gun, or had a loved one who has been shot and wounded or killed by a gun—including by gun suicide.

Everytown has done extensive research on gun violence trauma and has found that the impact of gun violence extends far beyond those killed or wounded (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-i). everytownresearch.org/report/gun-violence-survivors-america/; “When the Shooting Stops: “The Impact of Gun Violence on Survivors in America,” February 3, 2022, https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-impact-of-gun-violence-on-survivors-in-america/; and “Invisible Wounds: Gun Violence and Community Trauma among Black Americans,” May 27, 2021, https://everytownresearch.org/report/invisible-wounds-gun-violence-and-community-trauma-among-black-americans/. Go to reference Gunshot wound survivors face a lifelong healing process and may experience a broad array of difficulties, including psychological trauma, loss of work, and steep medical costs. Aside from immediate hospital bills associated with the wound, these survivors can encounter lifetime medical care costs, including readmission(s) to the hospital and nursing care. Many survivors report that the psychological effects of the shooting remain long after their injuries have physically healed. (Raza, Thiruchelvam, & Rdelmeier, July 2020); (Orlas & et al., 2021)

The prevalence and threat of shootings have created a generation of young people who are growing up in the United States with constant fear of being shot and killed in a place where they should feel safe. For students who have experienced other incidents of gun violence in their communities, the trauma symptoms are compounded. A 2022 national survey found that 51 percent of youth under the age of 18 are concerned that there will be a shooting in their or a nearby school, and 58 percent had recently thought about what would happen if someone with a gun entered their school or one nearby (Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab, et al., July 2023).

- everytownresearch.org/report/gun-violence-survivors-america/; “When the Shooting Stops: “The Impact of Gun Violence on Survivors in America,” February 3, 2022, https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-impact-of-gun-violence-on-survivors-in-america/; and “Invisible Wounds: Gun Violence and Community Trauma among Black Americans,” May 27, 2021, https://everytownresearch.org/report/invisible-wounds-gun-violence-and-community-trauma-among-black-americans/.

The Impact of Gun Violence Trauma

Gun violence trauma deeply alters lives, creating a collective experience that extends beyond geographic boundaries. “Collective trauma” refers to the psychological reactions to a traumatic event that affect an entire society. In this case, after an incident, a collective traumatic memory is produced that is remembered and recollected by community members through various times and spaces (Hirschberger, 2018).

After an incident of gun violence, 33 percent of survivors live in fear and feel unsafe. As exposure to gun violence erodes, survivors’ sense of safety—and ultimately, how they navigate their environments—heightened trauma responses, including hypervigilance, numbness, paranoia, anxiety, and depression. Nearly 50 percent of survivors said they needed support, services, or assistance to cope with the impact of gun violence within the first six months or more after the incident of gun violence (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-i). Many of those who have experienced trauma are at risk for being re-traumatized, which happens when someone suffers new traumatic stress reactions after another similar event.

The trauma of gun violence is immeasurable (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-i). It has lasting effects on individuals and communities that are directly and indirectly affected, with outcomes including post-traumatic stress disorder and secondary traumatic stress (STS). Those impacted by such trauma can include:

- Direct victims: Students and/or educators who directly experienced or witnessed gun violence may develop PTSD. This can include survivors of shootings, witnesses to shootings, or those who have had a loved one taken.

- First responders: First responders—such as police officers, paramedics, and healthcare professionals—are at risk of developing STS when they are exposed to gun violence.

- Community members: The broader community can also experience STS as a result of exposure to gun violence incidents. Community members may include friends, family members, neighbors, or even people who hear about an incident through media coverage.

- Educators: Educators may experience STS when working with students who have been directly or indirectly affected by gun violence.” Educators who are also on the “front lines” can be at risk for “compassion fatigue” (Psychology Today, 2024).

Effective Recovery Strategies

Association leaders and members should be included in this work. The U.S. Department of Education and other federal agencies recommend that emergency response planning teams for K-12 schools include “representatives from a wide range of school personnel, including, but not limited to, administrators, educators, school psychologists, nurses, facilities managers, transportation managers, food personnel, and family services representatives (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-a). In the context of higher education, they also suggest that the team include representatives from across the institution (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-b). Part Two of this guide, focusing on preparation for incidents of gun violence, describes the role of teams in more detail, including the need to ensure that emergency planning teams include and represent the needs of people with disabilities.

The federal agencies’ guides describe the four fundamental kinds of post-crisis recovery - academic recovery, physical recovery, fiscal recovery, and psychological and emotional recovery - and describe the types of functions that must be addressed in those four areas. The emergency operations planning team should consider some of the following questions when developing its goals, objectives, and courses of action for recovery efforts:

- Who will serve as the team leader?

- When should the education setting be closed and reopened?

- What alternative educational programming will students receive in the event that they cannot physically convene, and how will programming be provided?

- How will educators and the affected community receive timely and factual information regarding return to worksites?

- What, where, and who will provide counseling and psychological first aid?

- How will the immediate, short-term, and long-term counseling needs of students, educators, and families be addressed?

Release Consistent and Well-Timed Communication to Support Recovery Efforts

To address gun violence incidents, the administration and the association need to have a plan and strategy for ongoing communication with educators, students, parents, families, the community, and media. Consistent and well-timed communication helps maintain transparency, provide updated information, and address concerns. It also helps build trust, correct misinformation, and foster a sense of community. By managing media coverage responsibly, the association and the administration can ensure the well-being of those affected by the crisis and minimize the potential for re-traumatization. Overall, a well-structured and ongoing communications strategy plays a crucial role in facilitating recovery and rebuilding efforts after a gun violence incident.

The 2018 NEA School Crisis Guide offers communication strategies to support crisis response teams and recovery efforts (NEA, 2018):

- Provide regular and updated communications, even after the gun violence incident has passed;

- Update various communication channels, such as websites, voicemails, phone scripts, and fact sheets, as necessary;

- Maintain a master list of frequently asked questions and answers; and

- Conduct meetings with key stakeholders to identify questions, address rumors, and provide accurate and timely information.

Develop Longer-Term Media and Communications Strategy

In the days, weeks, months, and even years after the incident, the association and the administration will need to rely on a longer-term media and communications strategy outlining when, where, and how to communicate on the gun violence incident. This will include how and when to allow coverage of memorials and special events, building refurbishment or replacement, and examples of successful or challenging student and educator recoveries. Rely on the same approaches to media relations discussed in Part Three of this guide, related to responding to incidents of gun violence, including the need to be sensitive to the lasting trauma caused by the incident and to coordinate with administrators.

Facilitate Care and Support to Initiate Recovery After the Gun Violence Incident

The road to recovery can be long and difficult.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network—which states that the development of STS is recognized as a common occupational hazard for professionals working with traumatized children—offers resources on secondary traumatic stress for educators and other professionals exposed to secondary trauma, including for child-serving professionals (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2012); (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2011); (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2022); (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2008). The resources section of this guide includes links to the resources.

Promote Mental Health Services

Gun violence survivors—including students, educators, families, and community members—need trauma-informed counseling for both short- and long-term support. However, several barriers prevent survivors from accessing these services and care.

Findings from Everytown Support Fund show that survivors who identified as Black or Latin(o/a/x) were less likely to have access to mental health services or to providers culturally attuned to their communities, in the short- or long-term (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-i). When responding to a crisis in the community, all parties must ensure access to appropriate mental health services and support.

Promote Peer Support Groups

Peers are uniquely positioned to support survivors by drawing on their lived experiences. Studies have shown that peer support programs positively impact survivors by providing psychological and emotional support through community building, the credibility of lived experiences, and positive changes in acceptance of self and quality of life (Haas, Price, & Freeman, 2013), (Davis & et al., 2014), and (Hibbard & et al., 2002). Peers play an important role in trauma care and post-traumatic growth by enhancing collaboration, building trust, establishing safety and hope, and sharing stories of lived experiences to promote recovery and healing.

The association and the administration should consider working with mental health providers to establish peer support spaces for students and children to connect with one another in a healing environment. Educators may also benefit from peer support. The Everytown Survivor Network and other programs that support survivors of gun violence, such as the Survivor Fellowship Program for Students and The National Alliance for Children's Grief, serve as important resources. For additional resources, see the list at the end of this section of this guide.

Rely on Partnerships to Support Recovery Efforts

During and after a gun violence incident, partnerships are exceptionally important, both with the education community and broader community. Community partners—which can include racial and social justice organizations, mental health professionals, counselors, trauma specialists, and other support services—often provide diverse expertise, resources, and skills that can significantly enhance recovery efforts. Because they are already a part of the community, they also often are rooted in the local context and possess cultural competence because they already serve the community in crisis. Within the education community, organizations with expertise and experience likely already exist that can support effective recovery, like the Principal Recovery Network of the National Association of Secondary School Principals, a national network of current and former school leaders who have experienced gun violence tragedies in their buildings (National Association of Secondary School Principals, n.d.). The National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement also provides resources for educators and families.

From state to state and within states, potential partners may vary. An important place to start is with other unions representing workers in the Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education where association members work, gun violence-focused organizations, racial and social justice organizations, after-school programs, mental and physical health providers and organizations, associations representing principals or other administrators, and local colleges and universities with programs that identify or address violence in communities or, more specifically, in education settings.

The following list includes several national-level organizations—with links to their websites—that may have state or local counterparts. Identifying local groups working on similar topics may also serve the same purpose.

- AAPI Victory Alliance

https://aapivictoryalliance.com/gunviolenceprevention - AASA—The School Superintendents Association

https://www.aasa.org/resources/all-resources?Keywords=safety&RowsPerPage=20 - Alliance to Reclaim our Schools

https://reclaimourschools.org - American Academy of Pediatrics

https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/gun-violence-prevention - American Psychological Association

https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/gun-violence-prevention - American School Counselor Association

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Prevention-of-School-Rela - Color of Change

https://colorofchange.org - Community Justice Action Fund

https://www.cjactionfund.org - Hope and Heal Fund

https://hopeandhealfund.org/who-we-are - League of United Latin American Citizens

https://lulac.org/advocacy/resolutions/2013/resolution_on_gun_violence_prevention/index.html - Life Camp

https://www.peaceisalifestyle.com - Live Free

https://livefreeusa.org - March for Our Lives

https://marchforourlives.org/ - MomsRising

https://www.momsrising.org/blog/topics/gun-safety - NAACP

https://naacp.org - National Association of Elementary School Principals

https://www.naesp.org - National Association of School Nurses

https://www.nasn.org/blogs/nasn-inc/2023/07/27/take-action-to-address-gun-violence - National Association of School Psychologists

https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis - National Association of Secondary School Principals

https://www.nassp.org/community/principal-recovery-network - National Association of Social Workers

https://www.socialworkers.org/ - National PTA

https://www.pta.org/home/advocacy/federal-legislation/Public-Policy-Priorities/gun-safety-and-violence-prevention - National School Boards Association

https://www.nsba4safeschools.org/home - Parents Together

https://parents-together.org/the-heart-of-gun-safety-and-a-new-approach-to-advocacy - Sandy Hook Promise

https://www.sandyhookpromise.org - The Trevor Project

https://www.thetrevorproject.org - UnidosUS

https://unidosus.org/publications/latinos-and-gun-violence-prevention

Assessing Responses for Improvement or Adjustment

The gun violence recovery process is dynamic, and the needs of individuals and communities may change over time. Regular and continuous evaluation allows for adjustments to be made based on evolving circumstances and/or emerging needs. Evaluation can also help resource allocation and optimization based on assessing the impact of existing resources. The following are key principles for evaluating and adjusting a recovery plan, whether carried out by administrators or the association, or both:

- Implement a regular monitoring system to assess the recovery plan’s implementation, including milestones and key performance indicators;

- Solicit feedback from various stakeholders, including community members, educators, and mental health professionals, involved in the recovery process;

- Collect relevant data and information to assess the impact of implemented strategies;

- Maintain transparent communication about any adjustments made;

- Keep thorough documentation of evaluation or assessment, adjustments made, and why the changes were made.

By following the above principles, administrators and the association can ensure that the recovery plan remains responsive and supportive of the ongoing well-being of individuals and communities while also keeping in mind the importance of accommodating any unexpected changes. Educators should be ready to modify lesson plans, curriculum goals, classroom expectations, and organizational structure according to need. As the effects of trauma can be transformative, it is also important to be mindful of behavioral changes in students, notice any alarming patterns, lead with kindness and tolerance, and create room for discussion with students and their families.

Gun Violence Recovery Resources

References