Key Takeaways

- The first hours following a gun violence incident are likely to be fear-inducing, fast-moving, and chaotic. Safety and trauma-informed practices must be at the center of a school or association’s response.

- Use the short-term strategies in this part of the Gun Violence Prevention and Response Guide to direct how you talk to and support students after an incident and for guiding media response.

Gun Violence Response Executive Summary

The response section of the NEA School Gun Violence Prevention and Response Guide includes short-term measures to ensure coordinated and effective responses during and immediately after a gun violence incident to minimize harm; provide support to students, educators, and families; and facilitate communication with the media and the broader community. The recommendations in this part of the guide require coordination and rapid response during and immediately after a gun violence incident. For broader context and related recommendations, consult the other sections of this guide: Part One—Prevention, Part Two—Preparation, and Part Four—Recovery.

The first hours immediately following a gun violence incident are likely to be fear-inducing, fast-moving, and chaotic. It is critical that safety and trauma-informed practices are at the center of an association’s response. With many other moving pieces, it is important that the association coordinate with or, at a minimum, not undercut emergency response work.

The checklist for this section includes strategies and action steps based on how long ago the gun incident took place—the first few hours, the first 12 hours, and the first week and beyond. Those who have already done the preparation-related work identified in Part Two of the guide will be better equipped to implement the steps in the checklists, and they will be better prepared to identify how to adjust the steps as necessary given the particulars of the gun violence incident be addressed. In any case, effective responses will require coordination within and between components of the association and with administrators and law enforcement agencies, sensitivity to trauma, thoughtful communications, engagement with partners, and the provision of support for students and educators.

Talking with Students After an Incident

Key principles and suggestions to keep in mind when talking to students about a gun violence incident include:

- Creating a space for them to discuss and explore their feelings, assuring them that their fears are valid, and reminding them that there are safety measures in place;

- Letting students lead the conversation about safety and gun violence to find out what they know before sharing any information;

- Remembering that this is a collective trauma experienced by children, teens, and adults, and every person will react differently; and

- Supporting students after a gun violence incident involves understanding post-traumatic stress syndrome, grief, trauma, and loss.

Media Strategies

In the wake of a gun violence incident, it is important to have a plan and strategy for ongoing communication with educators, students, parents, the community, and the media. There are some key rules to ensure thoughtful communications and success in handling media inquiries and press, such as identifying a spokesperson who conveys two or three approved messages, with accuracy and empathy, to members and the public. When releasing information, it is essential that association leaders and members review and follow all district policies and state laws. The state affiliate and NEA are available to assist locals.

This section differs in structure from other sections in the guide because responding to a gun violence incident requires quick action under what may be extremely stressful circumstances, with incomplete information, potential life-and-death emergency responses, and fast-moving questions from members, families, and caregivers. It focuses on action steps for leaders and staff.

Identifying Resources to Support Students, Families, and Educators

Given the breadth of contexts in which incidents of gun violence take place, identifying a single set of resources to support students, educators, and families is not possible. NEA’s Gun Violence Response website includes multiple general resources. The Everytown Survivor Network amplifies the power of survivor voices, offers trauma-informed programs, provides information on direct services, and supports survivors in their advocacy.

In addition to the NEA and Everytown resources, this guide’s section on resources includes material from the American Psychological Association, the National Association of School Psychologists, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, the American School Counselor Association, Sandy Hook Promise, and the Coalition to Support Grieving Students, some geared toward Pre-K–12 contexts and some focused on institutions of higher education. When considering which resources to distribute, consider the specifics of the incident and the needs that the materials are designed to meet.

Building Strong Partnerships

Strong partnerships with local and statewide organizations provide the opportunity to enhance association work related to incidents of gun violence. This section of the guide includes links to national-level organizations that may have state or local-level counterparts. Identifying local groups—whether professional associations, non-governmental organizations, or academic centers—may also serve the same purpose. Identifying and building relationships with such groups that focus on racial and social justice, countering gun violence, promoting student health, or another relevant topic establishes mutual opportunities for support in response to the incident in the short, medium, and long term.

Overview

Keep four points in mind when reading this section of the guide:

- The first hours, in particular, are likely to be fear-inducing, fast-moving, and chaotic. The educators working in the building where the shooter is located will be focused on the very real threat to their lives and the lives of their students, colleagues, and visitors. Educators, students, and visitors in other buildings will also be concerned about their own safety.

- At this time, the physical safety of those involved in the incident and the use of trauma-informed practices when communicating or comforting is critical.

- Association work in response to gun incidents will take place within the context of many other moving pieces at the Pre-K–12 school or institution of higher education and in the broader community. It is important to coordinate or, at a minimum, be sensitive to not undercut emergency response efforts.

- NEA state and local associations vary greatly, including their experience and infrastructure for responding to gun violence; however, identifying and reaching out to colleagues who have addressed incidents of gun violence can be helpful.

Part 3: Response

Guidance for families and educators on how to address traumatic events with children.

Resources for post-secondary students to help them understand their reactions to traumatic events.

Constant and consistent communication helps maintain transparency, address concerns, build trust, correct misinformation, and foster a sense of community. Find guidance for managing media relations.

Find our comprehensive list of resources from NEA, Everytown for Gun Action, and other partners, including resources for addressing grief and trauma.

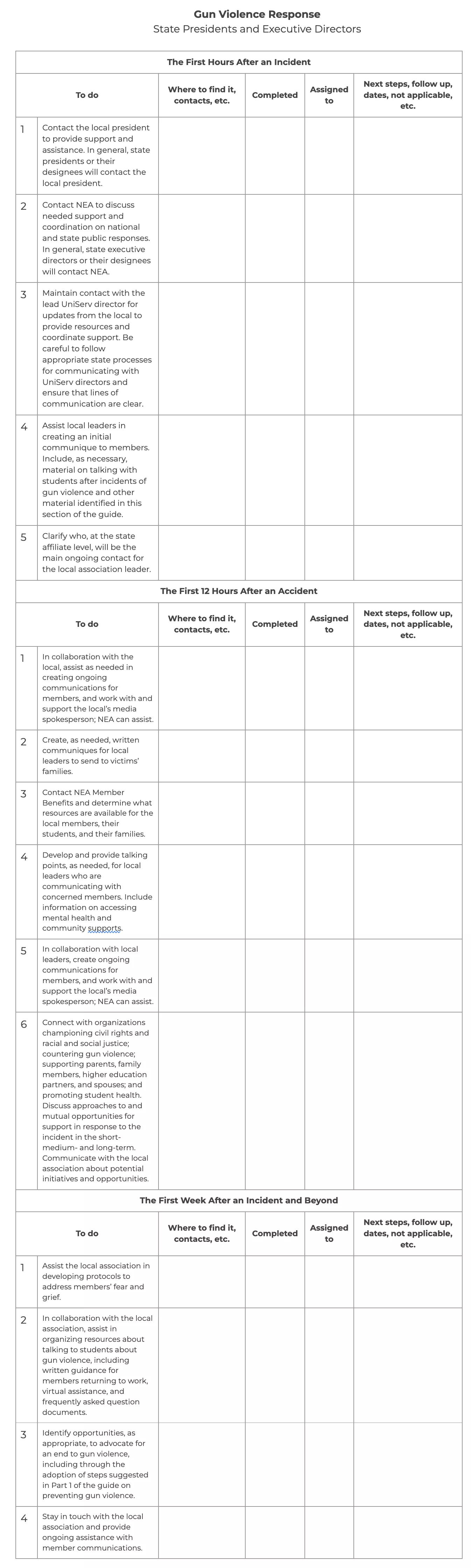

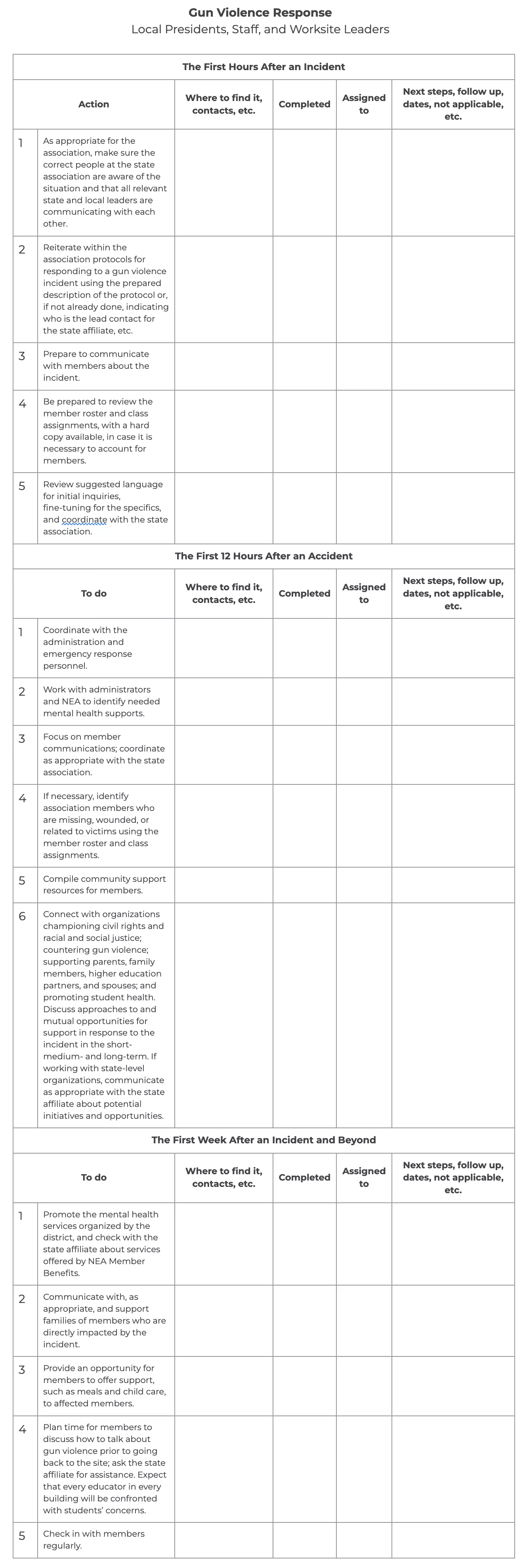

Download two checklists to help guide state and local affiliates as they develop their own gun violence prevention and response plans. The checklists include strategies and action steps based on how long ago the gun incident took place—the first few hours, the first 12 hours, and the first week and beyond.

How to Talk to K–12 Students About Gun Violence

Approaches to Talking About Traumatic Events

Parents and families of school-age children may feel uncertain about how to discuss an incident of gun violence in a way that does not cause further trauma. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network provides guidance to help families understand how children may react to such traumatic events (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, n.d.-a). The network also provide resources for adults, including strategies for coping with collective traumas (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2021).

Educators and families can foster healthy coping skills and mechanisms for children by:

- Promoting various emotional outlets for children, including art, music, sports, writing, games, and activities;

- Encouraging them to talk about their feelings routinely; and

- Initiating check-ins if they appear to be having a hard time.

Many educators also are concerned about discussing traumatic events and death; they may be afraid that raising the topic will upset students. However, the Coalition to Support Grieving Students—an organization of which NEA was a founding member—believes saying nothing can convey negative messages, including perceived insensitivity and disapproval (Coalition to Support Grieving Students, n.d.). By speaking up, educators can let grieving students know they recognize their situation and want to be supportive.

The American Psychological Association has produced guidance to help educators respond to students who may need support after a traumatic experience (American Psychological Association, 2021). Here are some tips for approaching those conversations:

- Make students feel physically and psychologically safe enough to share. Consistency and structure are important to create that feeling.

- Empathize and show sensitivity to students and remember that reactions to trauma may present as discipline problems.

- Validate the student’s experiences and feelings.

- Check in with students one

- Have patience. Students may take some time to recover. Remember that reactions to trauma can persist or suddenly appear long after the original event occurred.

Key Topics When Talking About an Incident

Following a gun violence incident, educators and families alike will be faced with questions and thoughts from students and children about what happened. It is important that, when discussing the following topics, educators and families consider employing these strategies.

- Safety

- Keep children and students grounded in the moment.

- Point out locks on doors, alarms, and security features.

- Look into specific safety procedures and precautions, and discuss the specific policies, people, and efforts already in place working to protect them.

- Allow children and students to think through and process their fear of danger.

- Don’t be dismissive of their inquiries, and allow them to further explore their needs.

- Gun Violence

- First, ask what they already know.

- Be straightforward and direct but gentle, leaving out graphic detail.

- Affirm this is an uncomfortable topic, and it is okay to be scared.

- Validate fears while reassuring their safety and reminding them of prevention efforts.

- Acknowledge the complexity of these emotions and encourage students and children to share any thoughts or questions that may later arise.

- Trauma

- Observe children’s and students’ behavioral and emotional changes, and practice tolerance for those changes, when appropriate.

- Understand that children, teens, and adults will be struggling with collective trauma that was brought on by gun violence (Abrams, 2023).

- Pay attention to signs that someone is struggling more than they let on; for example, a student or child may experience trouble sleeping, difficulty concentrating on schoolwork or chores, or changes in appetite or mood. Consult mental health practitioners.

- Understand what may bring on strong emotions for students and children. Take measures to reduce the risk of exposure to traumatic content.

- Grief and Loss

- Take a similar approach to the trauma-related steps outlined above.

- Use simple terms, and allow students and children to openly react, feel, and lead the conversation.

- Alert students and children of any alterations to their daily routine or schedule.

- Understand that persisting changes in behavior or concerning reactions may warrant professional attention.

Support for College Students After a Gun Violence Incident

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) produced College Students: Coping After the Recent Shooting, a resource that helps postsecondary students understand what to expect following a gun violence incident (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, n.d.-b). The document notes that “Understanding that the gun violence event has been an extremely frightening experience, and the days, weeks, and months following can be very stressful. How long it takes for an individual to cope depends on what they experienced during and after the shooting. If a student was injured during the event or lost friends or family, they may have a more difficult time coping. In the aftermath, it is difficult to figure out where to begin.” (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, n.d.-b)

Here is a summary of NCTSN’s useful resource, including common terms and reactions to these traumatic events.

Post-traumatic stress reactions are common, understandable, and expected, and they can be serious. There are three types of post-traumatic stress reactions:

- Intrusive reactions are ways in which the traumatic experience comes back to mind, including in dreams, thoughts, and images at various times;

- Avoidance and withdrawal reactions include staying away from people, places, or things that are reminders of the shooting or feeling emotionally numb, detached, or estranged from others.

- Physical reactions include sleep difficulties, poor concentration, irritability, jumpiness, nervousness, and being “on the lookout for danger.”

Reactions to danger refer to the sense that events or activities have the potential to cause harm. In the wake of a shooting, people and communities have greater appreciation for the enormous danger of violence and the need for effective emergency operations plans.

Depression is associated with the experience of loss, unwanted changes, or prolonged grief and is strongly related to the accumulation of post-violence adversities and the frustrations that accompany them.

Physical symptoms can occur even in the absence of any underlying physical injury or illness.

Trauma and loss reminders are things, events, situations, places, sensations, and even people that remind a person about a traumatic event or loss.

Media Relations and Other Communications After a Gun Violence Incident

In the wake of a gun violence incident, it is important to have a plan and strategy for ongoing communications with educators, students, families, the surrounding community, and the media. Constant and consistent communication helps maintain transparency, provide the most up-to-date information, and address concerns. It also helps build trust, correct misinformation, and foster a sense of community. Managing media coverage responsibly ensures the well-being of those affected by the crisis, minimizing the potential for re-traumatization. Overall, a well-structured and ongoing communication strategy plays a crucial role in facilitating recovery and rebuilding efforts after a gun violence incident.

Follow these key rules to maintain as much control over the situation as possible:

- Accuracy: Never guess, speculate, or predict the future. Don’t release information until you have verified its accuracy. Never go off the record. Always assume you are on the record, unless otherwise specified.

- Immediacy: Issue a basic accurate, factual initial statement as quickly as possible. Find resources to include in your media release in the related section of this guide. Be sure to confirm and reconfirm information at all points, and determine who and how the administration will provide information during a crisis. Gather information by asking the following:

- What happened?

- Who is in charge?

- Has the situation been contained?

- What is the status of the victim(s)?

- Did you have forewarning?

- Where do parents reunite with children?

- Key messages: Develop two or three key messages that are honest, consistent, responsive, and responsible. Strive to be positive and proactive.

- Location: Secure the location’s perimeter and determine where media will and will not be permitted. Designate a media area where all briefings will take place.

- Purpose: Use local media as a quick communications pipeline to key audiences but do not depend solely on the media.

- Policy: Make sure you follow all district policies and state laws when releasing information. Follow your crisis communications plan.

- Spokesperson: Designate a spokesperson and speak with one clear voice.

- Availability: Hold regular media briefings and respect deadlines. Avoid saying “no comment.” Provide a brief statement and then take a few questions, but stop when they get redundant or head off course.

- Attitude: Express sympathy, be calm, and remain respectful. Avoid getting defensive or placing blame.

- Care: Respect student and educator health, safety, and privacy rights.

- Privacy: Consider privacy issues and laws when thinking about releasing victim and perpetrator names—what are the roles of law enforcement, administrators, hospitals, and families in releasing names and conditions of victims? The administration should have a carefully considered and crafted policy regarding release of student and educator information, photos, and yearbooks that take into account applicable laws. Recognize that the media may use previously published photos of students participating in athletic or other events.

Manage Media Relations

The media will want ongoing information, so it is important that the designated spokesperson is available, open, and honest. Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education should develop media response and outreach strategies to be prepared for how to best provide this information.

It is important that everyone in the broader community understands the cycles of media response because the needs and desires of the media change as the situation evolves:

- Emergency Response: Initially, the media may be eager for information. Reporters will interview people willing to talk to them, often without verifying accuracy of information. The more factual information released, the less the media will have to rely on rumor and hearsay.

- What and Who: The media will want to know exactly what happened and who was involved—victims and perpetrators.

- Why and How: The media will ask why the crisis occurred and how it evolved. There will be a step-by-step dissection of the crisis.

- Analysis of Emergency Response: The media will analyze the crisis response: Did first responders react appropriately? Did the emergency operations plan work? How could it happen? As the situation stabilizes, the media will begin to look for causes of the tragedy and whether it could have been avoided. For example, they’ll ask if proper security measures were in place.

- Second-Day Stories: The media will begin to look for a different spin or angle, including emerging issues and people to interview. The media will also want to cover special events, such as memorials, the first day back, and athletic activities. Media protocols for special events are included in the related sections of this guide.

When communicating with the media, employ the following strategies:

- Determine when to talk to the media and identify an experienced spokesperson to field media questions and requests—if there is a public information officer, it is key that all educators and students should know how to refer media inquiries to this designated person.

- Identify tactics for answering media questions, sharing accurate and up-to-the-minute information, and developing positive working relationships with the media.

- Know who to contact and how to reach all local media, contacting them first because they will be in it for the long haul.

- Consider the feelings of victims and whether their talking to the media is healthy and appropriate.

- Develop templated news releases and advisories that can be quickly filled in and updated with information.

- Consider utilizing social media to amplify updates and statements, if appropriate.

- Coordinate, as appropriate, with district and/or municipal officials.

- Follow all district policies and state laws when releasing information to the media.

- Determine when to talk to the media and identify an experienced spokesperson to field media questions and requests—if there is a public information officer (a specific ICS role), it is key that all educators and students should know how to refer media inquiries to this designated person.

- Provide media training for educators as needed and identify a backup district spokesperson.

- Craft key messages about safety and talking points specific to the emergency or crisis, including talking points about transportation safety.

- Prepare a daily fact sheet.

- Identify the association expert who will provide guidance to educators on media interviews.

- Establish policies regarding media.

- Be prepared to manage media coverage of benchmark dates, anniversaries, etc.

Designate a Spokesperson to Serve Throughout the Crisis

If the administration has a communications office, the director of such an office is often the ideal spokesperson. The entity affected must determine carefully whether the principal, superintendent, school board or trustees, members, or state affiliate will make public statements and who is most appropriate to do so. Questions to consider when determining the appropriate spokesperson include:

- Is the official emotionally ready and able to give a statement?

- Does the community/media expect a high-level official to take an active, visible communications role?

- What are the legal considerations and long-term implications of any statement?

- Which official is appropriate? Who has the most information and represents the district best in the public arena?

Once the spokesperson is in place and/or other officials are assigned their roles, it is important that they are prepared to take on these roles. Here are some recommended action items:

- Provide talking points in writing.

- Prepare a list of frequently asked questions and answers.

- Practice and draft responses to questions, especially difficult ones.

- Determine a specific length of time for the interview or media conference, and ensure they begin and end on time.

- Have the communications director in charge and/or designated spokesperson (introduced as such) manage the question-and-answer period and decide when the interview should end.

- Meet with media spokespeople from law enforcement and the fire/rescue agencies to determine how to coordinate release of information.

- Develop a call log and track media calls, news agency and reporter names, and questions asked.

The association’s spokesperson should announce regularly scheduled press briefings. During the first few hours as the incident is unfolding, hourly press briefings or updates may be required, even if there is nothing new to report. That frequency can decrease as the situation stabilizes; however, the more information the association, district, or institution of higher education share with the media, the more they can control the story and ensure it is reported with accuracy. Those holding press briefings in the hours after an incident should report the following:

- How the identity of victims will be released: Names should not be released until they are verified and the families have been notified. Law enforcement, fire and rescue, hospitals, and families should be involved in this decision.

- Information about evacuation: The media are very helpful in getting information out quickly so that families know where their children are and how they can be reunited.

- Sympathy and acknowledgment of pain and grief: Victims, their families, and the community have experienced a traumatic event. They need to connect on a human level and feel the range of emotions associated with a crisis.

- Thanking individuals and agencies: Acknowledge the good work of educators, first responders, and community groups that helped with response efforts.

Build Strong Partnerships

Addressing gun violence in education settings requires strong, meaningful relationships with partners to deepen association understanding, build relationships, strengthen the processes and policies of Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education, and ensure that approaches developed to keep students, educators, and communities safe are culturally and racially appropriate.

From state to state and within states, potential partners may vary. An important place to start is with other unions representing workers in the Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education where association members work, gun violence-focused organizations, racial and social justice organizations, after-school programs, mental and physical health providers and organizations, associations representing principals or other administrators, and local colleges and universities with programs that identify or address violence in communities or, more specifically, in education settings.

The following list includes several national-level organizations—with links to their websites—that may have state or local counterparts. Identifying local groups working on similar topics may also serve the same purpose.

- AAPI Victory Alliance

https://aapivictoryalliance.com/gunviolenceprevention - AASA—The School Superintendents Association

https://www.aasa.org/resources/all-resources?Keywords=safety&RowsPerPage=20 - Alliance to Reclaim our Schools

https://reclaimourschools.org - American Academy of Pediatrics

https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/gun-violence-prevention - American Psychological Association

https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/gun-violence-prevention - American School Counselor Association

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Prevention-of-School-Rela - Color of Change

https://colorofchange.org - Community Justice Action Fund

https://www.cjactionfund.org - Hope and Heal Fund

https://hopeandhealfund.org/who-we-are - League of United Latin American Citizens

https://lulac.org/advocacy/resolutions/2013/resolution_on_gun_violence_prevention/index.html - Life Camp

https://www.peaceisalifestyle.com - Live Free

https://livefreeusa.org - March for Our Lives

https://marchforourlives.org/ - MomsRising

https://www.momsrising.org/blog/topics/gun-safety - NAACP

https://naacp.org - National Association of Elementary School Principals

https://www.naesp.org - National Association of School Nurses

https://www.nasn.org/blogs/nasn-inc/2023/07/27/take-action-to-address-gun-violence - National Association of School Psychologists

https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis - National Association of Secondary School Principals

https://www.nassp.org/community/principal-recovery-network - National Association of Social Workers

https://www.socialworkers.org/ - National PTA

https://www.pta.org/home/advocacy/federal-legislation/Public-Policy-Priorities/gun-safety-and-violence-prevention - National School Boards Association

https://www.nsba4safeschools.org/home - Parents Together

https://parents-together.org/the-heart-of-gun-safety-and-a-new-approach-to-advocacy - Sandy Hook Promise

https://www.sandyhookpromise.org - The Trevor Project

https://www.thetrevorproject.org - UnidosUS

https://unidosus.org/publications/latinos-and-gun-violence-prevention

Gun Violence Response Resources

Checklists

The checklists for this section includes strategies and action steps based on how long ago the gun incident took place—the first few hours, the first 12 hours, and the first week and beyond. Those who have already done the preparation-related work identified in Part Two of the guide will be better equipped to implement the steps in the checklists and better prepared to identify how to adjust the steps as necessary given the particulars of the gun violence incident be addressed. Effective responses will require coordination within and between components of the association and with administrators and law enforcement agencies, sensitivity to trauma, thoughtful communications, engagement with partners, and the provision of support for students and educators.