Key Takeaways

- Across all education settings, prevention efforts should be geared toward creating an environment that fosters trust-building, connection, and a sense of belonging for students. These efforts should include the use of trauma-informed and restorative practices.

- Educators can play a pivotal role in breaking the cycle of trauma and fostering a positive school climate, but their efforts must be supported with adequate funding and sufficient staffing.

- Promoting the adoption of gun violence-related bargaining language and administrative policy, including the creation or enhancement of health and safety committees, is another effective way to prevent gun violence.

Gun Violence Prevention Executive Summary

The prevention section of the NEA School Gun Violence Prevention and Response Guide highlights recommended strategies to reduce the risk and prevent the occurrence of gun violence incidents in education settings and communities. It includes taking actions to foster a positive and safe climate and limit access to firearms that could be used in acts of violence. For broader context and related recommendations, consult the other sections of this guide: Part Two—Preparation, Part Three—Response, and Part Four—Recovery.

The vast majority of the individuals who carried out a mass shooting in a Pre-K–12 school exhibited behaviors of concern in advance, and 75 percent of the time at least one person, often a peer, was aware of the plan (National Threat Assessment Center, 2019); (Violence Prevention Project, n.d.). Therefore, educators can play a pivotal role in breaking the cycle of trauma and fostering a positive school climate by:

- recognizing warning signs,

- having resources to address students’ mental health and emotional needs, and

- ensuring that racial profiling does not take place in the process are crucial to preventing gun violence in education settings.

To achieve these goals, adequate funding and sufficient staffing must be available.

This section also includes recommendations for the broader community, including anonymous reporting systems, the availability of community-based intervention programs that offer services to students off school grounds, and common-sense gun laws.

Bargaining language and administrative policy also offer important opportunities to enhance mental health supports and professional development on topics including trauma-informed crisis intervention and restorative practices.

Trauma-informed and restorative practices play a crucial role in maintaining strong connections between students, their peers, and educators within the school community. Across all education settings, prevention efforts are geared toward creating an environment that fosters trust-building and a sense of belonging for students.

Combating feelings of isolation and alienation among students relates directly to preventing gun violence because the majority of Pre-K–12 and higher education shooters maintained some level of affiliation with their educational institutions. Individuals who carried out a mass shooting in a Pre-K–12 school often exhibited behaviors of concern in advance, and 75 percent of the time at least one person, often a peer, was aware of the plan (National Threat Assessment Center, 2019); (Violence Prevention Project, n.d.).

Educators can play a pivotal role in breaking the cycle of trauma and fostering a positive school climate. Recognizing warning signs, having resources to address students’ mental health and emotional needs, and ensuring that racial profiling does not take place in the process are crucial to preventing gun violence in education settings. To achieve these goals, adequate funding and sufficient staffing must be available. Recognizing the warning signs is only a part of the solution; reducing access to guns is also critical.

This section also includes recommendations for the broader community. Anonymous reporting systems have demonstrated effectiveness, providing students and other community members with a trusted avenue to raise concerns related to student wellness and safety. These systems also serve as alerts for mental health professionals regarding interpersonal violence and suicide risks.

Considering that 4.6 million children under the age of 18 live in homes with guns, secure storage interventions play a critical role in overall school safety (Miller & Azrael, 2022). Additionally, community-based intervention programs offer services to students off school grounds and while traveling to and from school.

The evidence indicates that arming educators does not enhance student safety. In fact, it compromises the safe and trusting environment necessary to thwart gun violence, introducing new liability risks and complicating law enforcement responses in the event of an active shooter incident (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-d). In contrast, commonsense gun laws are essential for saving lives. Effective measures include:

- Require background checks on all gun sales, an approach proven to reduce gun violence;

- Pass Extreme Risk/Red Flag laws to provide a way for family members and law enforcement to petition a court to remove firearms from a person at risk of causing harm without a criminal proceeding;

- Pass secure firearm storage laws to prevent unauthorized access by children by requiring gun owners to lock up their firearms, which has been shown to prevent unintentional shootings and firearm suicides;

- Raise the age to purchase semi-automatic firearms to 21 to prevent potential younger shooters from easily obtaining such firearms;

- Prohibit guns on college campuses where legally viable to do so; and

- Prohibit assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, which allow shooters to fire more rounds over a short period of time and inflict more gunshot wounds during an attack.

Promoting the adoption of gun violence-related collective bargaining language and administrative policy, including the creation or enhancement of health and safety committees, is another effective way to combat gun violence. Bargaining language and administrative policy also offer important opportunities to enhance mental health supports and professional development on topics including trauma-informed crisis intervention and restorative practices.

Part 1: Prevention

Debunking misconceptions and better understanding the reality about gun violence in education settings.

Understanding the role of ACEs, childhood trauma, and toxic stress in gun violence in schools.

Looking at trauma-informed crisis intervention programs, community violence intervention programs, and active engagement strategies with students and parents.

Legislative and policy solutions for preventing gun violence.

Find our comprehensive list of resources from NEA, Everytown for Gun Action, and other partners, including resources for addressing grief and trauma.

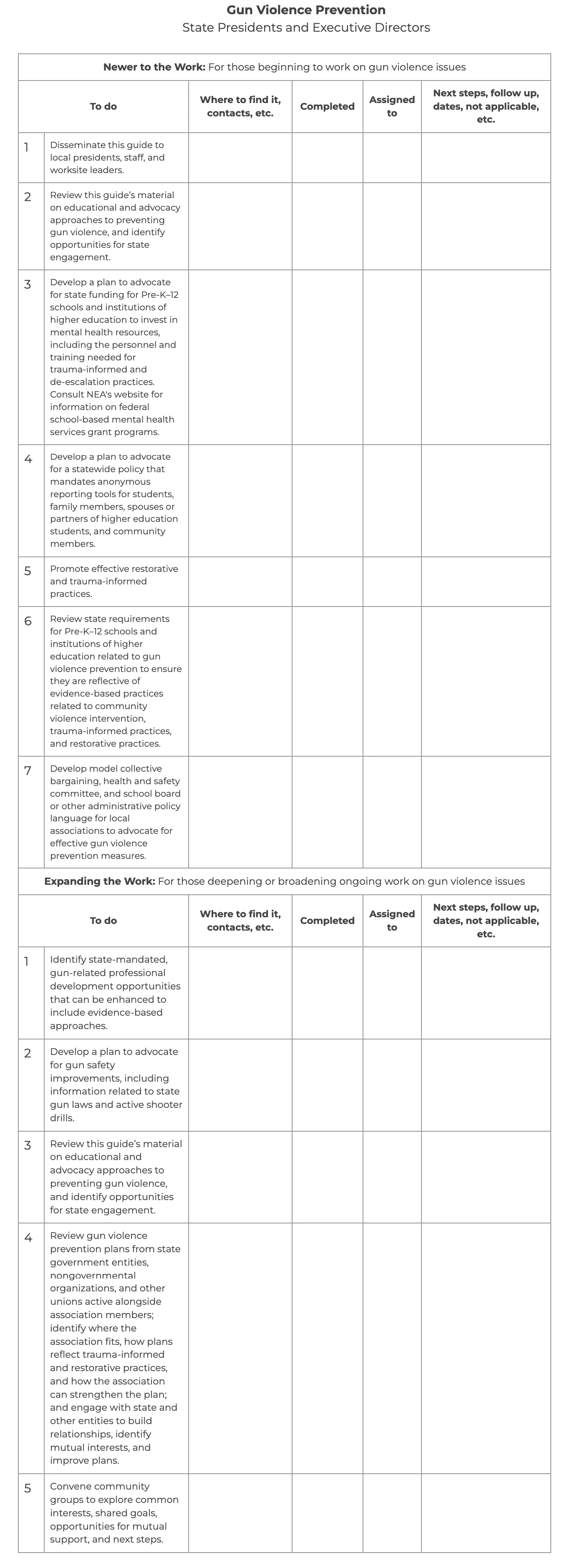

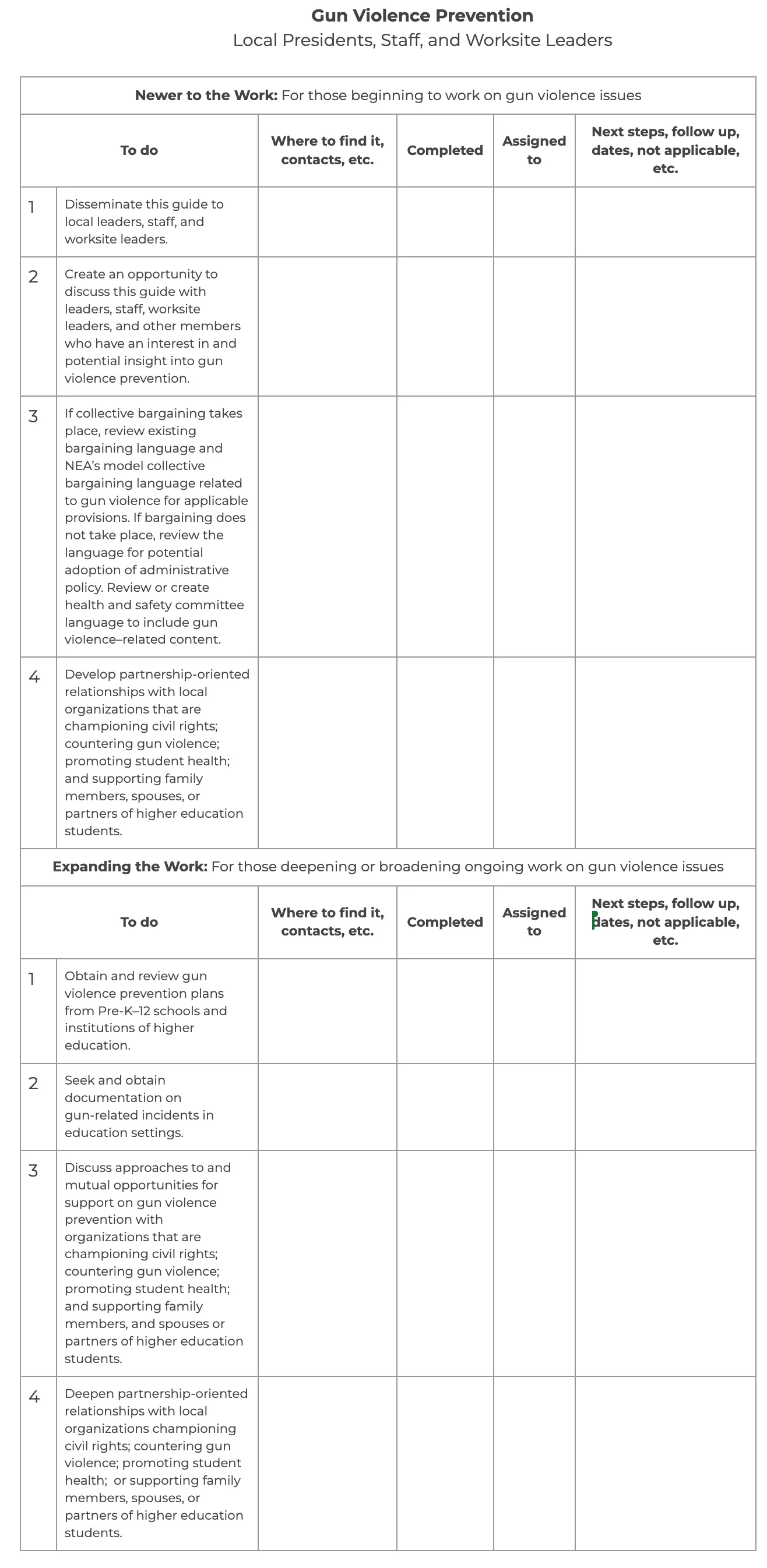

Download two checklists to help guide state and local affiliates as they develop their own gun violence prevention and response plans.

Background

According to the American Psychological Association, “A complex and variable constellation of risk and protective factors makes persons more or less likely to use a firearm against themselves or others. For this reason, there is no single profile that can reliably predict who will use a gun in a violent act. Instead, gun violence is associated with a confluence of individual, family, school, peer, community, and sociocultural risk factors that interact over time during childhood and adolescence” (American Psychological Association, 2013).

Given this complexity, taking meaningful actions to keep our students, educators, and surrounding communities safe must begin from an understanding of four key facts about gun violence in education settings.

Shooters Often Have a Connection to the Pre-K–12 School or Institution of Higher Education

In the Everytown for Gun Safety's on School Grounds database, 60 percent of school-age shooters were current or former students of the Pre-K–12 school, including all shooters involved in mass shootings and nearly all in self-harm incidents (96 percent) and unintentional discharges of a gun (91 percent) (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2022). For example, Everytown analyzed the New York City Police Department’s review of active shooter incidents in K–12 schools over the five-decade period from 1966 to 2016, finding that in 3 out of 4 of these incidents, the shooter or shooters were school-age and were current or former students (New York City Police Department, 2016). Everytown limited its analysis of this data to incidents that took place in K–12 schools and defined school-age as under the age of 21. Go to reference Similarly, the Violence Prevention Project found 89 percent of shooters at colleges and universities had a connection to the institution (Violence Prevention Project, n.d.). These data suggest the need for comprehensive strategies that combine prevention, mental health support, and crisis response to effectively tackle school gun violence.

- 1 Everytown limited its analysis of this data to incidents that took place in K–12 schools and defined school-age as under the age of 21.

Debunking Myths and Misconceptions About Gun Violence

Guns Discharged in Pre-K–12 Schools Generally Come from the Home of a Parent or Close Relative

School-age shooters generally do not purchase the weapon or weapons used. In a study of targeted K–12 school violence from 2008 to 2017, the U.S. Secret Service noted that 3 out of 4 shooters acquired their firearm from the home of a parent or close relative (National Threat Assessment Center, 2019). This was the case, for example, with the Oxford High School shooting on November 30, 2021, in Michigan (Albeck-Ripka & Kasakove, 2021).

There Are Nearly Always Warning Signs

Warning signs of school shootings, if appropriately identified, can offer an opportunity for intervention beforehand. However—as discussed in more detail in the sections that follow on trauma-informed intervention practices and restorative disciplinary practices—identifying and intervening based on advanced indicators is essential but must be done without perpetuating adverse racial stereotypes targetting those that demonstrate behavioral concerns, or compromising the trust and emotional safety of a school environment.

The U.S. Secret Service study of targeted school violence from 2008 to 2017 found that 100 percent of the perpetrators showed behaviors of concern and 77 percent of the time at least one person most often a peer knew about their plan (National Threat Assessment Center, 2019). In the higher education context, about 44 percent of people who perpetrated mass shootings had communicated their intent in advance (Peterson & et al., 2021).

The U.S. Secret Service study of targeted school violence from 2008 to 2017 found that 100 percent of the perpetrators showed behaviors of concern and 77 percent of the time at least one person, most often a peer, knew about their plan.

These data suggest that fostering a trusting and emotionally safe climate where students are willing to ask adults for help and report any statements and behaviors of concern, such as gun threats on social media or weapons carrying can be effective tools for prevention. Addressing warning signs and taking immediate action, while also ensuring that racial profiling is never supported or permitted, is essential.

The Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting on December 14, 2012, in Connecticut, underscores the importance of intervening when possible to stop violence before it happens. The official investigation revealed that there were several instances of the shooter’s prior behavior that were concerning. For example, when the shooter was in seventh grade, a teacher reported that “his writing assignments obsessed about battles, destruction and war, far more than others his age. The level of violence in the writing was disturbing” (Sedensky, 2013).

Gun Violence in U.S. Schools Disproportionately Affects Students of Color

In the shooting incidents where the Everytown Support Fund was able to identify the racial makeup of the student body, 2 out of 3 incidents occurred in majority-minority schools (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2022). Everytown gathered demographic information on the student population of each school included in our Gunfire on School Grounds database for which data were available, comprising 552 of 569 incidents. A majority-minority school is defined as one in which one or more racial and/or ethnic minorities constitute a majority of the student population. Go to reference Although Black students represent approximately 15 percent of the total K–12 school population in the United States (National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, 2020), they make up 30 percent of the average population at schools that have been affected by a fatal shooting (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2022). Everytown averaged the student population size, both total and Black student populations, for the years 2013 to 2021. Data at the national level for demographics of the student population at preschools is not available. Go to reference While perpetrators of mass shootings in schools have tended to be White, and mass shootings are often portrayed in media coverage as occurring predominantly in schools with a majority of White students, gunfire on school grounds disproportionately affects students of color.

- 2 Everytown gathered demographic information on the student population of each school included in our Gunfire on School Grounds database for which data were available, comprising 552 of 569 incidents. A majority-minority school is defined as one in which one or more racial and/or ethnic minorities constitute a majority of the student population.

- 3 Everytown averaged the student population size, both total and Black student populations, for the years 2013 to 2021. Data at the national level for demographics of the student population at preschools is not available.

Adverse Childhood Experiences, Childhood Trauma, Grief and Toxic Stress

Gun violence—in a community, a home environment, or an education setting—can be a factor that produces trauma and stress for children and adults. A 2021 analysis of mass shooting data showed that a majority of mass shooters experienced early childhood trauma and exposure to violence at a young age and had an identifiable grievance or crisis event (Shahid & Duzor, 2021). The analysis also found that shooters studied the actions of past shooters, sought validation for their methods and motives, and had the means to carry out an attack. Go to reference NEA’s website provides additional information on toxic stress and trauma. Therefore, it is important to understand the potential impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress when addressing an incident of gun violence. Educators can play a pivotal role in breaking the cycle of trauma through early detection and focused support. To achieve this goal, state legislatures must fully fund and staff schools so that educators have the time and attention to recognize early warning signs and take action to address students’ needs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 64 percent of adults in the United States reported having at least one type of adverse childhood experience (ACE) before the age of 18. The CDC also noted that ACE events are typically the result of violence, abuse, neglect, and environmental factors that expose children to substance abuse, mental health-related issues, and parental separation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.).

Experiencing adversity, including trauma and toxic stress, can significantly shape an individual’s health and life outcomes. Childhood trauma can also negatively affect the mental health of, and educational outcomes for, higher education students.

Trauma occurs when someone feels threatened by serious harm, whether it is physical, mental, or emotional. While not all ACEs lead to childhood trauma, people who suffer from one or more such adversities may experience a negative impact on their overall well-being, education, and career. Researchers have found that trauma can change the brain and the body’s makeup, which can lead to diseases like obesity, heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and mental health disorders (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014). Neuropsychologists have found that traumatic experiences can, in fact, alter a child’s brain, activating its “fight, flight, or freeze” responses and reducing the areas where learning, especially in regard to language, occurs. When this shift happens repeatedly, it fundamentally changes the brain, particularly for children under the age of 5, to adapt and survive under the worst conditions (Flannery, Mary Ellen, 2016).

The ongoing presence of ACEs may also contribute to toxic stress. The American Academy of Pediatrics defines “toxic stress” as prolonged or significant adversity in the absence of mitigating social-emotional buffers, such as a supportive adult. This kind of persistent activation of the stress response systems can result in a wide array of biological changes that occur at the molecular, cellular, and behavioral levels; disrupt the development of brain architecture; and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment well into adulthood (Garner & Yogman, 2021).

Experiencing adversity, including trauma and toxic stress, can significantly shape an individual’s health and life outcomes. Childhood trauma can also negatively affect the mental health of and educational outcomes for higher education students (Lecy & Osteen, 2022); (Assari & Landarani, 2018).

Many other factors have been proven to cause toxic stress, including poverty, racism, bullying, community violence, and generational (historical) trauma (Cronholm & et al., 2015); (Garner & Yogman, 2021). According to researchers at the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University, ACEs-generated trauma includes community and systemic threats from inside or outside the home environment because the brain recognizes a present threat and goes on high alert (Center on the Developing Child, 2020).

Childhood bereavement can also have a significant impact on children’s health and well-being. “The death of someone close to a child has a profound and lifelong effect on the child and may result in a range of both and short- and long-term reactions” (Schonfeld & Demaria, 2016). Schools can learn more about the impact of bereavement and becoming grief-sensitive schools to better support student learning and development. Organizations such as the Coalition to Support Grieving Students provide resources to assist schools in becoming grief-sensitive.

- 4 The analysis also found that shooters studied the actions of past shooters, sought validation for their methods and motives, and had the means to carry out an attack.

Prevention Strategies

Education settings at all levels must establish safe, supportive, nurturing environments where students can thrive. Strategies including trauma-informed crisis intervention programs and active engagement with students and their families are essential to gun violence prevention. In addition, community violence intervention programs that integrate mental health and emotional supports help address the systemic and underlying factors that can lead to gun violence.

Foster Safe and Supportive School Climates

When schools are adaptable to the needs of their students, educators, families, and community, they can provide students with care and compassion and create conditions that prevent shootings and other violence. For example, a community school that has high levels of violence inside or outside the school building may fund programs that create safe walking and transportation routes to and from school, often referred to as safe passage; grant alternatives to out-of-school suspensions that offer meaningful educational opportunities for students; provide family counseling; increase access to mentoring, both inside and outside of school; and incorporate restorative justice into disciplinary policies. NEA’s website includes additional information on community schools.

Students are often the first to notice signs that a peer is in crisis, has brought a weapon to school, or has shared plans to commit a violent act; however, they are sometimes reluctant to share these observations—or their own personal struggles and needs—with adults they do not trust. Students may be reticent to relay information that might help avert a gun violence incident because of fear of getting in trouble, being labeled a “tattletale,” or not being believed or taken seriously. A pre-established relationship of trust with at least one educator increases students’ willingness to report potential incidents or identify bullying or violence they experience or witness (Volungis & Goodman, 2017).

Many education support professionals (ESPs) live in the same community as their students and are often trusted confidants; they play a key role in the preventative and intervention actions. ESPs—including, but not limited to, custodial and maintenance, food service, clerical, security, and transportation professionals— are often the first to confront a shooter. Indeed, almost half of NEA ESP members—48 percent—spend a great deal of their time promoting school safety. The job responsibilities of another 28 percent are somewhat related to promoting such work.

To build trust, educators must have cultural competency to counteract unconscious bias and reduce the risk of biased decision-making that can impede a student’s ability to trust them.

An all-staff activity called Know Me, Know My Name is an example of an effective way to identify students who may need support but go unseen (Illinois Education Association, n.d.). Low-cost and relatively simple, the activity helps educators identify children who may need adult intervention via outreach and relationship-building, encompassing the ideals of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships (SSNR). SSNRs help interrupt cycles of violence and reduce the impact of students’ exposure to abuse and neglect. The Harvard School of Education also developed relationship mapping, which is another example of this type of activity (Harvard Graduate School of Education, n.d.).

NEA’s Vision for Safe, Just, and Equitable Schools

NEA's vision for safe, just, and equitable schools consists of thriving spaces that are safe and welcoming for all students; are discriminatory toward none; integrate the social, emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual needs of the whole student; and equitably and fully fund the community school model with wraparound services and resources (NEA, 2022).

The resources in this guide can help make this vision a reality. NEA’s website includes additional information on cultural competency, racial justice systems, and addressing unconscious bias.

Implement Trauma-Informed and Grief-Sensitive Crisis Intervention and Restorative Disciplinary Practices

Students who commit acts of gun-related violence in schools almost always have shown warning signs that concerned other people around them (National Threat Assessment Center, 2019, p. 58). Therefore, identifying students who may need support to prevent a crisis from becoming violent while ensuring that racial profiling and other biased actions are neither supported nor permitted, is key to preventing gun violence in schools.

To respond to signs of distress in a manner that serves students and protects the community, schools can convene a multidisciplinary team that uses trauma-informed and grief-sensitive crisis intervention practices in collaboration with other community partners. A School Improvement Team, Resilience Team, Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) Team, or other such entities that may already exist could potentially serve this function. Whatever its name, such a team would receive information about a student who may be in crisis, evaluate the situation, design interventions to prevent violence, and provide appropriate in-school engagement, support, and resources. Every team that addresses crisis intervention should include ESPs; however, ESP membership must be voluntary. Every school community is different, so team structures and functions must be designed and implemented based on the unique needs of the student body and the broader school community.

Identifying students who may need support to prevent a crisis—while ensuring that racial profiling and other biased actions are neither supported nor permitted—is key to preventing gun violence in school.

Behavioral threat assessments are frequently used to identify students who are at risk of committing violence and get them the help they need. These programs generally consist of multidisciplinary teams that are specifically trained to intervene at the earliest warning signs of potential violence and divert those who would do harm to themselves or others to appropriate treatment. NEA opposes “behavioral threat assessment programs and approaches that disproportionately target Native students and students of color” (NEA, 2023). The Association urges all school community members to be prepared to ensure that if they use behavioral threat assessments, they achieve their desired outcomes without adverse racial impact. If such assessments are in use, they must be properly resourced, including with release time for the counselors, nurses, or other educators who serve on a team conducting behavioral threat assessments.

NEA does not believe that the criminalization and over-policing of students is the right approach to addressing gun violence in education settings. Research shows that exclusionary discipline programs, including zero-tolerance policies, disproportionately impact students of color and contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline, including through their subjective application toward students of color (Ford, 2021). Zero-tolerance policies and harsh disciplinary practices result in negative academic outcomes for students given that school suspensions are a stronger predictor of dropping out of school than grade-point average and socioeconomic status (Suh & Suh, 2007). Furthermore, a longitudinal study done with children ages 9 and 10 found that “enforcing these kinds of disciplinary actions can impair typical childhood development, leading to academic failure, student dropout, and emotional and psychological distress, disproportionately affecting Black children, multiracial Black children, and children from single-parent homes (Fadus & et al., 2021).

Exclusionary discipline programs, including zero-tolerance policies, disproportionately impact students of color and contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline, including through their subjective application toward students of color.

By contrast, NEA emphasizes the use of behavioral practices centered in restorative justice and the elimination of inequitable policies, practices, and systems that disproportionately harm Native People and People of Color—including those who are LGBTQ+, have disabilities, and/or are multilingual learners—and deprive many students of future opportunities. Trauma-informed prevention strategies should include restorative-based practices.

Engage School Communities in Gun Violence Prevention Efforts

School safety requires all stakeholders—students, families, educators, educators’ unions, mental health professionals, law enforcement professionals, organizations promoting racial and social justice, and community members—to collaborate and work together.

Here are examples of how to engage students and families in gun violence prevention:

- Create a safety reporting program. These programs should ensure all students, families, educators, and community members are aware of the reporting system so that they have a trusted avenue to raise concerns when issues of student wellness or safety arise. In a four-year study of the Say Something Anonymous Reporting System (SS-ARS) in a school district in the southeastern United States, more than half of firearm-related tips were deemed “life safety” events, requiring an immediate response from the school team and emergency services. The SS-ARS also identified tips related to interpersonal violence and suicide concerns, which both have implications for firearm violence. Research suggests that adolescent firearm injuries often stem from interpersonal violence, and firearm use significantly escalates the risk for self-inflicted injury and suicide completion. It is imperative that awareness of such reporting systems is amplified to increase use by the community, particularly students; however, it likely requires additional investment in supports and services for adolescents to help mitigate the burden on those who respond to these tips (Thulin & et al., 2024). State initiatives—like Utah’s SafeUT crisis chat and tip line, which is used in almost all K–12 schools and some institutions of higher education in the state, by the Utah National Guard, and with first responders and their families—can also serve this function (SafeUT, n.d.).

In higher education contexts, there are greater restrictions on how schools can communicate with parents and families than in elementary, middle, and high schools.

- Help families start conversations with their school community. When families communicate openly, honestly, and directly with school officials, educators, and administrators, they can help prevent gun violence. Stand with Parkland developed the resource “5 Questions Every Family Should Ask as the School Year Begins” to assist families in ensuring their children’s safety and better understand how prepared a school is to address safety issues (Stand with Parkland, n.d.).

- Use strategies that encourage effective communication on difficult topics. The NEA Health and Safety Program partnered with the Right Question Institute and the Brown School of Public Health to provide a training module to help support families, educators, and students effectively communicate around health and safety issues. The Association also produced a training module—Pathways for Effective School-Family Partnerships: A Strategy for Productive School Health and Safety Dialogue. This training is based on the Right Question Institute’s Question Formulation Technique (QFT), a structured method for generating and improving questions that can be used by individuals or groups.

Promote Secure Storage Practices to Keep School Communities Safe

Evidence strongly suggests that secure firearm storage—storing guns unloaded, locked, and separated from the ammunition—is essential to any effective strategy to keep students, educators, schools, and communities safe (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-d). One study showed that the majority of children are aware of where their parents store their guns. More than one-third of those children reported handling their parents’ guns, many doing so without the knowledge of their parents (Baxley & Miller, 2006).

Secure firearm storage—storing guns unloaded, locked, and separated from the ammunition—is essential to any effective strategy to keep schools, students, and communities safe.

Secure storage not only decreases the likelihood of gun violence on school grounds, but it also reduces firearm suicide rates. A recent study of two decades of suicide prevention laws showed that the rate of gun suicide among young people ages 10 to 24 years old was lower in 2022 than in 1999 in states with the most protective secure gun storage laws, which hold gun owners accountable for failing to store their firearms securely. In states with no secure storage laws or only reckless access storage laws, the gun suicide rate among young people ages 10 to 24 years old increased by 36 percent from 1999 to 2022 (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-h).

In states where colleges and universities are required to allow firearms on campus, schools should encourage students to securely store their firearms.

The Value of Trauma-Informed Practices

Researchers have defined trauma-informed practices (TIP), as a set of approaches that address the impact of trauma by creating a safe and caring environment. TIP includes restorative practices and a focus on creating a safe school culture, building relationships, and supporting students’ self-efficacy. When effectively implemented, these practices can reduce instances of bullying and aggression, improve achievement, increase self-esteem for students, improve connections between students and educators as well as among students, and strengthen social and emotional skills. By doing so, schools can create school climates where gun violence is less likely (Lodi & et al., 2021).

The entire school community must receive training to successfully implement a restorative practices discipline model. Ineffective training and partial implementation can contribute to frustration and skepticism about such initiatives.

NEA’s guidance on trauma-informed practices provides a list of common actions that educators can take to implement across educational settings, which include the following:

- Support students from the bus stop to the classroom (and beyond!);

- Be aware of what may upset a student;

- Show compassion, not judgment;

- Give students a safe space to share and express their feelings;

- Help students develop a growth mindset;

- Use restorative practices that minimize punitive discipline outcomes;

- Build relationships;

- Meet students where they are;

- Don’t ignore possible “warning signs”;

- Take care of yourself; and

- Encourage all educators to be trained on trauma-informed practices.

Educators can encourage a culture of secure gun storage by increasing awareness of secure storage practices. One example of an effective awareness campaign is the Everytown Support Fund’s Be SMART program, which focuses on fostering conversations with other adults about secure gun storage. Although educators may be familiar with the SMART acronym for goal-setting purposes, in this context, the acronym stands for Secure guns in homes and vehicles, Model responsible behavior, Ask about unsecured guns in homes, Recognize the role of guns in suicide, and Tell your peers to be SMART. The program’s purpose is to facilitate behavior change for adults and help parents and adults prevent child gun deaths and injuries (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-d).

Schools can partner with Be SMART and pass resolutions requiring that all student households receive Be SMART information, which is already happening in Los Angeles, San Diego, and Denver, among other locations (Sawchuk, 2021). School districts across the country have taken this vital action, impacting more than 10 million students (Everytown for Gun Safety, 2023-j), and some institutions of higher education have partnered with the program. Be SMART's Secure Storage Toolkit provides all the information and resources you need to encourage your school to pass a secure storage resolution.

Governors, federal and state departments of health and education, legislatures, nonprofit organizations, and local officials can also work together to develop and fund programs that increase awareness of the need to store firearms securely. For example, see the City Gun Violence Reduction Insight Portal (CityGRIP), available at www.citygrip.org. Go to reference

Increase Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Support

Firearms are the leading cause of death among youth in the United States, and firearm suicides account for more than 4 out of 10 of these deaths. The rate of firearm suicide among young people (ages 10 to 24 years old) increased by 30 percent from 1999 to 2022 (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-h). Experts are sounding the alarm about young people’s mental health. A recent survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that, overall, 42 percent of teens experienced a persistent feeling of sadness or hopelessness, while 57 percent of female and 29 percent of male respondents felt that way. The same survey found that, overall, 22 percent of teens seriously considered attempting suicide, while 30 percent of female respondents and 14 percent of male respondents did (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021, p. 63). For many reasons including the prevalence of guns in our society the elevated risk for youth gun suicide continues to rise. Furthermore, a large proportion of perpetrators of mass shootings expressed suicidal intentions, suggesting suicide prevention through crisis intervention could be a meaningful mitigating factor for mass shooting incidents (Violence Prevention Project, 2021); (Remnick, 2022).

School-employed health professionals, who navigate the education system and the challenges of emotional and social development, serve as a critical resource for students. These professionals may be among the first to know when students are experiencing difficulties or when they are at risk of turning to violence. Unfortunately, the current national shortage of specialized school-based counselors, psychologists, sociologists, and nurses means that meeting the needs of students can be a challenge, and this challenge is often exacerbated in under-resourced communities. NEA determined in the report NEA determined in the report “Elevating the Education Professions: Solving Educator Shortages by Making Public Education an Attractive and Competitive Career Path” that solving educator shortages requires evidence-based, long-term strategies to address both recruitment and retention. The report noted that mental health positions were among the most understaffed in schools (NEA, 2022-a).

School-based health services, including behavioral health, provide crucial support to students. School-based Medicaid services, for example, play an essential role in the health of children and adolescents, including those related to behavioral health. With more than 41 million kids covered by Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the school setting offers a unique opportunity to meet children where they are (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023). Schools, early childhood settings, and local education agencies help support children and their families, providing children and youth with access to important healthcare services on-site. For information on how to utilize the historic investment into school-based services by the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, see NEA’s Your Guide to the BSCA. NEA’s website also includes guidance on bargaining and advocacy tactics to support educators’ mental health.

School-based health centers (SBHCs) can also help make quality primary care more accessible for children and adolescents (Kjolhede & et al., 2021). “School-based health care advances health equity for children and adolescents who experience barriers to accessing care because of systemic inequities, their family income, or where they live,” according to the School-Based Health Alliance. “School-based health centers, the most comprehensive type of school-based health care, do this by providing primary, behavioral, oral, and vision care where youth spend most of their time at school” (School-Based Health Alliance, 2024). These organizations can collaborate with schools to support student well-being by contributing clinical expertise to supplement existing services at the school (National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2023, p. 6).

The trauma that comes from the threat of gun violence is deeply affecting the mental health and well-being of not only students but also educators. The needs of educators are too often overlooked when resources are being offered in schools to address trauma from gun violence. There must be an increase in support and mental health resources for educators to sustain the workforce as they continue to face the threat of gun violence in schools.

Through NEA Member Benefits, NEA members receive access to the NEA Mental Health Program, powered by AbleTo, which provides 24/7 access to “evidence-backed tools for stress, anxiety, depression, or whatever you’re going through.”

The federal government’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Disaster Distress Helpline offers free, 24/7 crisis counseling for people experiencing emotional distress related to any natural or human-caused disaster, including shootings. Dial or text 1-800-985-5990 to connect with counselors in more than 100 languages via third-party interpretation services.

Programs that help educators recognize the warning signs of mental health issues include Emotional CPR and Mental Health First Aid.

Help is also available for individuals who are struggling or in crisis by calling or texting 988 or chatting at 988lifeline.org. State initiatives, like SafeUT described earlier in this section, on anonymous reporting for school safety can also provide mental health support for Pre-K–12 and higher education students.

Integrate Community Violence Intervention Programs into Schools

Community violence occurring in and around schools significantly affects students and educators. An assessment of the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) showed that witnessing community violence was linked to elevated odds of gun carrying, substance use, and suicide risk among Black, Hispanic, and White students, regardless of gender (Harper & et al., 2023).

In neighborhoods that experience community violence, schools can support Community Violence Intervention (CVI) strategies to mitigate its impact on youth (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-i). Examples of these programs include the following:

- Safe passage programs provide safe routes to and from schools to reduce student exposure to gun violence. To achieve this goal, educators, law enforcement groups, and communities collaboratively implement protocols and procedures to ensure student safety (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-k). A longitudinal study analyzing data from 2005 to 2016 found that following the program’s implementation, incidents of crime along these routes dropped an average of 28 percent for simple assault and battery; there was a 32 percent reduction in aggravated assault and battery. Furthermore, overall weekday criminal incidents on school grounds decreased by an average of 39 percent per year where safe passage programs were implemented (Sanfelice, 2019).

- School-based violence prevention programs provide students and educators with information about violence, change how youth think and feel about violence, and enhance interpersonal and emotional skills. Chicago’s Becoming a Man (BAM) program—one example of a school-based violence prevention program—has reduced juvenile justice system readmission by 80 percent (Heller et al., 2016).

- Youth engagement and employment programs support students outside of schools (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-f). These programs often center on healing or personal development. For example, The TraRon Center helps youth gun violence survivors in Washington, D.C., heal through after-school art therapy (TraRon Center, 2024). Programs focusing on youth employment also show success. For example, a researcher found that participation in Boston’s Summer Youth Engagement Program led to a decrease in participants’ violent crime arraignments by 35 percent in the 17 months after program completion (Modestino, 2019).

- Crime prevention through environmental design involves deliberate efforts to change the built environment of neighborhoods, buildings, and grounds to reduce crime and increase community safety (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2021-a); (CityGRIP, n.d.). Programs encompass a wide variety of approaches and efforts to rehabilitate areas and discourage violence through visible signs that a community is cared for and watched over. Because gun violence is so costly and these simple fixes are not, communities save hundreds of dollars for every dollar that is invested (Branas & et al., 2016).

Together, these programs offer services to students going to and from school and students on and off school and building grounds.

Do Not Arm Teachers or Other Educators

Arming teachers and other educators does not make schools safer; to the contrary, it escalates the risk of shootings and introduces new liability risks (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-d). As noted earlier in this guide, many educators, parents, and school safety experts, including several law enforcement groups, are opposed to arming teachers.

Research strongly indicates that children will access guns when guns are present, including on school grounds. There have been numerous incidents of misplaced guns in schools that were left in bathrooms (Metrick, 2016), in locker rooms (Associated Press, 2018), and at sporting events (Laine, 2019).

For more on school resource officers and policing in school, see this guide’s section on school policing. Everytown’s Students Demand Action website includes additional information on strategies to oppose arming teachers.

Advocacy-Based Prevention Strategies

Advocate for Measures That Limit Access to Guns

Gun safety policies save lives. The Everytown Support Fund’s Gun Law Rankings, which compare the gun violence prevention policies of all 50 states, show a strong correlation between a state’s gun laws and its rate of gun deaths. States with strong gun safety regulations, such as the policies outlined below, have lower rates of gun violence. States with weaker gun laws, such as no-permit carry and Shoot First laws (also known as Stand Your Ground laws), have higher rates of gun violence (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-a). The following gun violence prevention policies save lives and reduce the toll of gun violence on communities:

- Requiring Background Checks on All Gun Sales: Background checks are proven to reduce gun violence. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia already require a background check on all handgun sales (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-g). An Everytown Support Fund investigation showed that as many as 1-in-9 people looking to buy a firearm on this country’s largest online gun marketplace cannot legally purchase firearms—including those under the age of 18 (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2021-b). As part of a comprehensive plan to prevent gun violence in education settings, states and the federal government must pass laws that require background checks on all gun sales so that adolescents and people prohibited from possessing firearms cannot easily purchase them from unlicensed sellers.

- Enacting Extreme Risk/Red Flag Laws: Prior to the shooting at Parkland, Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, on February 14, 2018, nearly 30 people knew about the shooter’s previous violent behavior, and law enforcement groups had been called to incidents involving the shooter on dozens of occasions (Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, 2019, p. 264). This is just one of many examples where a school shooter displayed warning signs of potential violence. States must enact Extreme Risk laws to create a legal process by which law enforcement, family members, and possibly educators can petition a court to temporarily prevent an individual from accessing firearms when there is evidence that they are at serious risk of harming themselves or others. These Extreme Risk protection orders, sometimes also called red flag orders or gun violence restraining orders, provide a way for concerned bystanders to intervene without a criminal proceeding against a potentially dangerous individual. Extreme Risk protection orders include robust due process protections. The court issues final orders after a hearing.

- Enacting Secure Firearm Storage: Studies show that secure firearm storage laws save lives, particularly by preventing unintentional shootings and firearm suicides. For example, one study found that households that locked both firearms and ammunition had a 78 percent lower risk of self-inflicted firearm injuries and an 85 percent lower risk of unintentional firearm injuries among children and teenagers, compared to those households that left firearms and/or ammunition unlocked (Grossman & et al., 2005). To protect kids in and out of schools, states must enact and enforce secure firearm storage laws. More than half of states and the District of Columbia currently have some form of secure storage law (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-f). In addition, several cities, including New York City and San Francisco, have passed secure storage laws.

- Raising the Age to Purchase Semi-Automatic Firearms: Under federal law, a person must be 21 years old to purchase a handgun from a licensed gun dealer.

18 U.S.C.§ 922(b)(1).

Go to reference

However, a person only needs to be 18 years old to purchase that same handgun through an unlicensed sale (such as unlicensed sellers offering guns for sale online or at gun shows) or purchase a rifle or shotgun from a licensed dealer.

18 U.S.C.§ 922(b)(1); 18 U.S.C. § 922(x)(2).

Go to reference

Research shows that 18- to 20-year-olds commit gun homicides at triple the rate of adults 21 and over.

Everytown Research analysis using FBI Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) and U.S. Census American Community Survey data 2016–2020.

Go to reference

Despite evidence that most perpetrators of school shootings are school-age and have a connection to the school, many states have failed to step in to close these gaps that easily allow firearm access for 18- to 20-year-olds (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-c).

Only six states and DC require a person to be 21 to possess a handgun—DC, DE (beginning in July 2025), IL, MA, MD, NJ, and NY. Only IL and DC require a person to be 21 to possess a rifle or shotgun, and eight states require a person to be 21 to purchase a rifle or shotgun—CA, CO, DE, DC, FL, HI, IL, VT, and WA.

Go to reference

At a minimum, states and the federal government must raise the minimum age to 21 years old to purchase or possess handguns and semi-automatic rifles and shotguns to prevent younger shooters from easily obtaining firearms.

- Keeping Guns of College Campuses: The vast majority of colleges and universities prohibit guns from being carried on campus, either by state law or school policy. Institutions of higher education have unique risk factors, such as high rates of student mental health challenges and increased use of alcohol and drugs, which make the presence of guns potentially deadly. By contrast, some states require colleges and universities to permit guns to be carried on campus under some circumstances (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-e). Supporting the enactment by federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal governments of statutes, rules, and regulations that would prohibit people other than law enforcement agents from possessing firearms on the property of institutions of higher education, the American Bar Association (ABA) noted evidence suggesting that “permissive concealed gun carrying generally will increase crime and place students at risk.” Despite state laws allowing firearms in institutions of higher education, those institutions may still have independent authority to prohibit guns

The American Bar Association (ABA)—citing recent authority holding that new bans on guns on campus should be permitted—highlighted that “a unanimous Montana Supreme Court ruled that state legislators infringed on authority granted to higher education officials by the state constitution by passing a law that permitted open and concealed firearm carrying on university and college campuses. The court declared that ‘maintaining a safe and secure education environment’ fell within the Board of Regents’ purview (and implicitly, that the Board could determine it was necessary to maintain that environment by prohibiting firearms on campus), and recognized that ‘Montana is not immune from the catastrophic loss that follows the use of firearms on school campuses.’” The ABA also called for “states that do not make it unlawful for any person, other than law enforcement, to possess firearms on property owned, operated, or controlled by any public institute of higher education, authorize such institutions of higher education to restrict or regulate the concealed or open carry of firearms on their campuses.”

Go to reference

(American Bar Association, 2023).

In states where colleges and universities are required to allow firearms on campus, schools should encourage students to securely store their firearms.

- Prohibiting Assault Weapons and High-Capacity Magazines: Assault weapons are generally high-powered semi-automatic rifles specifically designed to allow shooters to wound and kill many people quickly. When combined with high-capacity magazines—commonly defined as magazines capable of holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition—a shooter is able to fire more rounds over a short period without pausing to reload. The more rounds a shooter can fire consecutively, the more gunshot wounds they can inflict during an attack. From 2015 to 2022, incidents where individuals used an assault weapon to kill four or more people resulted in 23 times as many people wounded on average compared to those who did not use an assault weapon (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-a). Numerous mass shooters in schools, including those responsible for two of the deadliest shootings since 2016, have used assault weapons and high-capacity magazines (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2023-a). NEA and Everytown recommend that states prohibit the possession and sale of assault weapons and magazines capable of holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition.

For more on strategies to advocate for measures that limit access to guns, see NEA’s Legislative Program and Everytown’s Moms Demand Action and Students Demand Action.

Promote Strong Bargaining Language and Administrative Policies

NEA provides guidance on how to secure language regarding aspects of working conditions surrounding gun violence in administrative policies, employee handbooks, and collective bargaining agreements. This bargaining support includes language on:

- Prohibition against arming educators;

- Violence/abuse and threats against educators;

- Support after an assault;

- Broad health and safety provisions for overall safe work environments; and

- Joint health and safety committees.

- 5 For example, see the City Gun Violence Reduction Insight Portal (CityGRIP), available at www.citygrip.org.

- 6 18 U.S.C.§ 922(b)(1).

- 7 18 U.S.C.§ 922(b)(1); 18 U.S.C. § 922(x)(2).

- 8 Everytown Research analysis using FBI Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) and U.S. Census American Community Survey data 2016–2020.

- 9 Only six states and DC require a person to be 21 to possess a handgun—DC, DE (beginning in July 2025), IL, MA, MD, NJ, and NY. Only IL and DC require a person to be 21 to possess a rifle or shotgun, and eight states require a person to be 21 to purchase a rifle or shotgun—CA, CO, DE, DC, FL, HI, IL, VT, and WA.

- 10 The American Bar Association (ABA)—citing recent authority holding that new bans on guns on campus should be permitted—highlighted that “a unanimous Montana Supreme Court ruled that state legislators infringed on authority granted to higher education officials by the state constitution by passing a law that permitted open and concealed firearm carrying on university and college campuses. The court declared that ‘maintaining a safe and secure education environment’ fell within the Board of Regents’ purview (and implicitly, that the Board could determine it was necessary to maintain that environment by prohibiting firearms on campus), and recognized that ‘Montana is not immune from the catastrophic loss that follows the use of firearms on school campuses.’” The ABA also called for “states that do not make it unlawful for any person, other than law enforcement, to possess firearms on property owned, operated, or controlled by any public institute of higher education, authorize such institutions of higher education to restrict or regulate the concealed or open carry of firearms on their campuses.”

Promoting Strong Union-Backed Language on School Safety

The San Diego Education Association bargained language on school safety plans that ensures the association is involved in the process of keeping schools safe. The language includes “rules and procedures to be followed by site personnel for their protection, including a method of emergency communication and rules and regulations governing the entering and leaving of school sites.” The language requires that school safety plans explicitly address weapons (Board of Education of the San Diego Unified School District and the San Diego Education Association, 2022).

In another example, Racine Educators United (REU), in Wisconsin, has aggressively organized around safety concerns in the district, leading, in part, to the creation of the School Safety Committee, an advisory group including five representatives selected by REU and five chosen by the Racine Unified School District (RUSD). Together, REU and RUSD will select parent, student, and community representatives to serve on the committee. The district superintendent also appoints a building services representative. The committee was a settlement of REU grievances and an REU lawsuit against the district.

According to the agreement between REU and RUSD, the School Safety Committee’s review of district policies and procedures will be informed by trauma-sensitive and restorative justice practices and will cover topics including weapons policies, responding to weapons, and gun violence and active shooter response (Racine Unified School District and Racine Educators United, 2024).

Build Strong Partnerships

Addressing gun violence in education settings requires strong, meaningful relationships with partners to deepen association understanding, build relationships, strengthen the processes and policies of Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education, and ensure that approaches developed to keep students, educators, and communities safe are culturally and racially appropriate.

From state to state and within states, potential partners may vary. An important place to start is with other unions representing workers in the Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education where association members work, gun violence-focused organizations, racial and social justice organizations, after-school programs, mental and physical health providers and organizations, associations representing principals or other administrators, and local colleges and universities with programs that identify or address violence in communities or, more specifically, in education settings.

The following list includes several national-level organizations—with links to their websites—that may have state or local counterparts. Identifying local groups working on similar topics may also serve the same purpose.

- AAPI Victory Alliance

https://aapivictoryalliance.com/gunviolenceprevention - AASA—The School Superintendents Association

https://www.aasa.org/resources/all-resources?Keywords=safety&RowsPerPage=20 - Alliance to Reclaim our Schools

https://reclaimourschools.org - American Academy of Pediatrics

https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/gun-violence-prevention - American Psychological Association

https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/gun-violence-prevention - American School Counselor Association

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Prevention-of-School-Rela - Color of Change

https://colorofchange.org - Community Justice Action Fund

https://www.cjactionfund.org - Hope and Heal Fund

https://hopeandhealfund.org/who-we-are - League of United Latin American Citizens

https://lulac.org/advocacy/resolutions/2013/resolution_on_gun_violence_prevention/index.html - Life Camp

https://www.peaceisalifestyle.com - Live Free

https://livefreeusa.org - March for Our Lives

https://marchforourlives.org/ - MomsRising

https://www.momsrising.org/blog/topics/gun-safety - NAACP

https://naacp.org - National Association of Elementary School Principals

https://www.naesp.org - National Association of School Nurses

https://www.nasn.org/blogs/nasn-inc/2023/07/27/take-action-to-address-gun-violence - National Association of School Psychologists

https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis - National Association of Secondary School Principals

https://www.nassp.org/community/principal-recovery-network - National Association of Social Workers

https://www.socialworkers.org/ - National PTA

https://www.pta.org/home/advocacy/federal-legislation/Public-Policy-Priorities/gun-safety-and-violence-prevention - National School Boards Association

https://www.nsba4safeschools.org/home - Parents Together

https://parents-together.org/the-heart-of-gun-safety-and-a-new-approach-to-advocacy - Sandy Hook Promise

https://www.sandyhookpromise.org - The Trevor Project

https://www.thetrevorproject.org - UnidosUS

https://unidosus.org/publications/latinos-and-gun-violence-prevention

Engage State Occupational Safety and Health Agencies

State and local associations in any of the 29 states that have created state occupational safety and health agencies can look to the state agency for advocacy and organizing opportunities related to gun violence in Pre-K-12 public schools and public institutions of higher education. The federal government’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) serves to ensure safe and healthy working conditions for the private sector. Federal OSHA does not have jurisdiction over state and local public sector workers. Where established, state agencies are required by federal law to be at least as effective as OSHA in protecting workers and in preventing work-related injuries, illnesses, and deaths. Go to reference

In states with a safety and health agency covering public employees but without a workplace violence standard, the association or an individual member can file a complaint if workplace conditions are unsafe. Workplace violence standards allow for the association and members to be involved in the development and review of worksite violence plans. The state of New York has established a workplace violence prevention standard applicable to public schools (New York State, 2024), and California is developing one.

Promote Professional Development, Capacity-Building, and Staffing

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Education have awarded $1.5 billion in short-term grants for school safety, improved access to mental health services, and support for young people to address trauma and grief from gun violence. The U.S. Department of Justice has awarded an additional $60 million in short-term grants. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) commits to expanding the pipeline by designating $500 million for training to increase the pool of skilled professionals providing mental health services in schools.

In early 2024, Vice President Harris announced an additional $285 million in funding for schools to hire and train mental health counselors (Psychiatrist.com, 2024). Grants are not meant to be the long-term solution, but they can assist school districts with infrastructure needs and the ability to hire and train counselors, psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals.

To identify funding opportunities for mental health support in education settings, see NEA’s webpage on school-based mental health services grants. In addition, explore whether state-mandated professional development for educators includes trainings on suicide prevention, trauma-informed crisis intervention, de-escalation techniques, restorative practices, and trauma-informed strategies.

Get Involved in Local Government

Educators play an essential role in the communities in which they work. The experience they’ve gained while working with students gives them a unique perspective when it comes to making public education policy, negotiating collective bargaining agreements, and setting budget priorities for their communities.

- 11 The federal government’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) serves to ensure safe and healthy working conditions for the private sector. Federal OSHA does not have jurisdiction over state and local public sector workers. Where established, state agencies are required by federal law to be at least as effective as OSHA in protecting workers and in preventing work-related injuries, illnesses, and deaths.