NEA Today-Retired August 2022

How to Launch a Second Career

As much as you loved being a teacher, did you ever dream of following a completely different path? Learn how retired educators have pursued new passions and built second careers—including as a mayor, writer, and barber

shop owner.

What I’ve Learned

Retiree Marilyn Warner shares her story of gratitude, determination, and lessons learned as she recovered from a stroke.

The Time Is Now to Protect Democracy

Members vowed to fight for freedom at the 2022 NEA-Retired Annual Meeting.

The 2022 Elections Are Coming!

This cheat sheet explains how candidates up and down the ballot can impact students and educators.

Take This Job and Love It

As many educators leave the profession, find out why so many more have stayed.

2022 Teacher of the Year

Ohio history teacher Kurt Russell fosters open conversations about race.

Censored!

Find out how educators are fighting back against gag orders and intimidation.

Solving for X

Paid leave, LGBTQ+ rights, and child care are just a few of the problems that union members are solving together.

Spotting Students’ Mental Health Struggles

“ESPs … can see patterns in students’ lives that teachers can’t see,” says educator and author Lori Desautels, who writes about the important role education support professionals can play in recognizing mental health concerns.

The Bulletin Board

NEA-Retired members across the country are making a difference.

From the NEA-Retired President

Becky's Journal of Joy, Justice, and Excellence

NEA's president visits schools in Polk County, Georgia, speaks at an event on preventing gun violence, and suggests three things to do at the start of this school year.

2022 NEA Representative Assembly

Vice President Kamala Harris, NEA leaders, and many others celebrated and inspired educators.

NEA In Action

NEA is working every day for great public schools for all students and educators.

First & Foremost

Education News and Trends

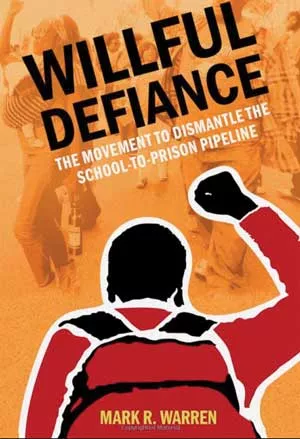

Q&A: How Educators Can Help Dismantle the School-to-Prison Pipeline

During the 1990s, many school districts adopted zero-tolerance policies, mandating suspensions for what school officials called “willful defiance” for minor offenses such as cursing, chewing gum, or refusing to take off a hat. This gave way to unjust disciplinary actions that disproportionately put students of color on a path toward the criminal justice system.

In the recent book, Willful Defiance: The Movement to Dismantle the School-to-Prison Pipeline, researcher, author, and NEA higher education member Mark R. Warren spotlights the voices of parents and students of color who are organizing and building movements to stop the school-to-prison pipeline.

NEA: The book describes how kids are getting expelled based on willful defiance or subjective judgments, such as “disruptive,” “annoying,” and “boisterous” behaviors. What’s really at the root of these suspensions?

Mark R. Warren: First, we must understand zero-tolerance discipline and policing in our schools. The term zero-tolerance started in the 1980s with the war on drugs and then was transferred into schools during the 1990s. It’s a part of what civil rights lawyer and author Michelle Alexander called “the new Jim Crow” and the rise of mass incarceration and criminalization in communities of color.

The general public and many teachers had attitudes rooted in racist stereotypes. They targeted African American and Latino young people as superpredators, criminals, or bad people who must be disciplined and controlled and, on the basis of any small misbehavior, removed from our schools.

To help drill down, what questions should teachers and school staff consider before taking any action toward a student?

MRW: When teachers are sitting in a classroom, one of the questions to ask is, “Am I acting in a way that’s part of the system that’s criminalizing our young people, or is there a different way of thinking about what’s going on in front of me and supporting our students and their families?”

There are many educators who would be mortified at the thought of contributing to educational injustice for students of color. What are some practices and behaviors educators need to recognize and/or adopt to ensure they’re a part of the solution, not the problem?

MRW: One thing educators can do is think about alternatives to discipline and punishment. There are a whole set of restorative practices and restorative justice approaches that help with student misbehavior.

What would also be helpful is for educators to look at the adults who have set up this system of discipline and punishment in schools and in our larger society. Who is being disciplined and punished? What do the disparities look like? What are the

attitudes and habitual practices, such as calling the police or school resource officer for minor issues, or when there is a disagreement over whether a student has a cell phone on their person? It’s the larger system, not just student misbehavior, that needs to be addressed.

Willful Defiance chronicles how, in the past, teachers unions were in favor of zero-tolerance policies. How do you envision unions being better partners?

MRW: It’s the same question for the union as it is for an individual educator. Are you acting in a way that is supporting a school-to-prison pipeline, or are you working to dismantle it? In the book, I document how many teachers’ unions opposed efforts by Black community members who were fighting for educational justice for their children. That’s the reality we must face. Rather than opposing parents and young people who are organizing to change racist policies and practices, unions should find common ground and start to listen.

Take Action

Find out how you can advocate for racial and social justice in our schools at neaedjustice.org.

MISSING:

Future Teachers in Colleges of Education

When it comes to the U.S. teacher shortage, the candle is burning at both ends. More stressed-out teachers are leaving the profession, and, at the same time, the number of college students preparing to teach is still falling, according to a report from the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE).

Among AACTE’s findings:

- In 2019, U.S. colleges awarded fewer than 90,000 undergraduate degrees in education, down from nearly 200,000 per year in the early 1970s.

- In the last 10 years alone, the number of people completing traditional teacher-prep programs has dropped by 35 percent.

- The number of students earning degrees in science and math education—high-need subjects in U.S. schools—has fallen by 27 percent.

None of this is surprising to NEA members, who have been talking for years about the escalating educator shortage, which has now grown to encompass other positions such as bus drivers, school nurses, and food service workers.

Quoted

“Forcing American taxpayers to fund private religious education—even when those private schools fail to meet education standards, intentionally discriminate against students, or use public funds to promote religious training, worship, and instruction—erodes the foundation of our democracy and harms students.”

—NEA President Becky Pringle reacts to the U.S. Supreme Court’s Carson v. Makin ruling, which could expand the reach of school vouchers across the nation

U.S. Public Schools

48,847,268 STUDENTS

In fall 2020, U.S. public schools enrolled 48,847,268 students, a decrease of 2.7 percent from fall 2019. From the 2020 – 2021 school year to the 2021 – 2022 school year, enrollment is expected to decline by an estimated 0.1 percent.

3,192,309 TEACHERS

U.S. public schools employed 3,192,309 teachers during the 2020 – 2021 school year. The number of teachers is expected to increase slightly by 0.1 percent

for the 2021 – 2022 school year.

$14,360 EXPENDITURE

The national average per-student expenditure during the 2020 – 2021 school year, based on fall enrollment, was $14,360—a gain of 5 percent from 2019 – 2020.

$15,047 EXPENDITURE

Per-student expenditure is projected to increase by 4.8 percent to $15,047 in 2021 – 2022.

SOURCE: 2022 NEA RANKINGS AND ESTIMATES

Why Students Play School Sports–or Don’t

Student participation in school sports tends to dip by the time young people reach high school. A recent survey asked nearly 6,000 high school students why they chose to play, or not to play, school sports.

Top Reasons Students Engage in High School Sports

81% Having Fun

79% Exercise

66% Learning and improving skills

64% Playing with and making new friends

59% Competing

53% Winning games

Top Reasons Students Don’t Play High School Sports

42% Schoolwork

32% Don’t enjoy sports

26% No sports offered that are of interest

25% Don’t think they’re good enough

22% Work schedule

21% Family responsibilities

SOURCE: NATIONAL STUDENT SURVEY ANALYSIS, ASPEN STUDENT AND RESONANT EDUCATION, 2022

Media coverage drives public opinion on K–12 teachers

About 2/3 of teachers say the news media substantially impacts how they feel about their jobs and negatively impacts the teacher pipeline.

Communities valuing teachers:

79% OF TEACHERS and 71% OF PARENTS believe the news media substantially impacts how much communities value K–12 public school teachers.

Government policies affecting teachers:

77% OF TEACHERS and 69% OF PARENTS say the media substantially impacts government policies affecting K–12 education.

People pursuing teaching careers:

64% OF TEACHERS and 54% OF PARENTS say the media impacts how many people pursue teaching careers.

SOURCE: TEACHERS IN THE NEWS: A PUBLIC AGENDA PROJECT; ILLUSTRATION: HARU_NATSU_KOBO

Issues & Impact

Educators and Allies Fighting for Public Schools.

5 Big Reasons to Strengthen Bargaining for Public Employees

We need a federal law that protects educators’ right to collective bargaining

By Amanda Litvinov

The pandemic has underscored the vital contributions of educators and other public employees who support our communities every day. Time and again, we’ve seen these brave workers—including nurses, social workers, child care providers, firefighters, sanitation workers, and millions of educators—put themselves at risk to care for the most vulnerable among us.

Yet in many places, educators and other public employees don’t have a say in their working conditions or the jobs they do. Often they can’t weigh in on what they need to get the job done, despite their expertise and experience.

A patchwork of state laws?—developed over the decades in varying political climates—determine whether or not public servants have the right to bargain collectively. Public employees deserve a federal law that guarantees them the right to form a union and to bargain for the raises and working conditions they deserve.

How does collective bargaining help students and educators?

Collective bargaining rights give educators a seat at the table to negotiate fair wages, working hours, and benefits, including health care, pensions, and paid leave. During the pandemic, some locals bargained for more nurses, counselors, and literacy specialists to support students and make caseloads more manageable.

Studies also show that collective bargaining decreases wage inequality, especially for People of Color and women.

In other words, collective bargaining for public employees is good public policy.

Why is collective bargaining under attack?

Unfortunately, anti-union politicians and their backers have worked to erode these rights in recent decades. Some states have gutted their public sector collective bargaining laws and have severely restricted bargaining rights for educators and other public employees.

In 2011, the Wisconsin state legislature passed just such a law prohibiting public sector workers, including educators, from bargaining on any employment issue except base wages. Many other states—including Iowa, Michigan, West Virginia, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Montana—followed Wisconsin’s lead, either curtailing or eliminating collective bargaining rights.

Across the country, NEA affiliates are working to reverse this trend by working with state legislators to establish, restore, or defend collective bargaining.

NEA also supports a bill in the U.S. Congress called the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act, which would ensure that public employees can exercise important workers’ rights, such as:

- Joining a union that they select.

- Having clear dispute resolution procedures.

- Bargaining over wages, hours, and terms and conditions of employment.

Take Action

Ask your representatives in the U.S. Congress to support the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act, and tell congressional leadership to bring it to the floor for a vote.

Go to nea.org/publicservice to make your voice heard.

The Benefits of Collective Bargaining for Public Education

Learn more at nea.org/bcg.

1. Better school days for educators and students

- Guaranteed recess periods.

- Time for teachers and paraeducators to share best practices.

- Educator input in their own professional learning.

2. Educator-led answers to student needs

- Smaller class sizes and caseloads.

- More specialized instructional support personnel, such as social workers, occupational therapists, library media specialists, and many other positions.

- Bolstering arts curricula.

3. Tool to help retain high-quality employees

- Higher salaries.

- More teacher preparation.

- Mentoring and induction programs for new teachers.

- Better working conditions.

4. Safer school buildings

- Agreements to address the safe return to in-person learning during the pandemic.

- Lead and radon testing.

- Air quality monitoring.

- Repair and upgrades to address unsafe conditions.

5. Bargaining for the Common Good

- This innovative approach to bargaining brings together educator unions, parents, and community allies to improve schools. The far-reaching results can include:

- Contract campaigns that benefit educators and the broader community.

- Changes that do away with racist policies and practices.

- Communities standing together to demand change.

BE LIKE JILL:

Get active in your union

NEA Today: What inspired you to become active in your union?

Jill Grimm: When I was first hired, I joined the Teachers Association of Anne Arundel County (TAAAC) without a second thought. Then I had a powerful experience teaching labor-movement history to my eighth graders, and it inspired me to get more involved in my local beyond just voting once a year and paying my dues. I have been a building rep for many years and served on the negotiation team. I also joined the board of directors this year.

Why did you say yes to joining the negotiations team?

JG: Since I got to Anne Arundel County, I was very passionate about making sure we speak out about professional wages. It’s basically expected that teachers earn a master’s degree, but we can’t afford graduate programs on our salaries. We have new teachers who can’t afford to live in the county we work in because their salaries don’t match the cost of living.

I also thought it was important to make sure middle school educators are represented on the bargaining team, because elementary and high school concerns are often quite different.

Why is it important for educators to make their voices heard with school boards and district administrators?

JG: If you’re not being seen and heard, you’re allowing decision-makers to say, “Oh, whatever we do is fine with educators because they’re not speaking out.” When we write letters, make calls, attend board of education meetings, or testify at public hearings, we can influence important things like school start times or how pandemic relief money should be spent.

For example, our school board told us, “We’re $110,000 short, we can’t pay teachers more this year.” And the year before, they couldn’t do it because of uncertainty around the economic picture due to COVID-19. But we had research reports and knew that Anne Arundel County had enough money to pay us more. So we started reaching out to school board members, the county executive, and members of the county council—not just the negotiations team, but TAAAC members—saying we know this is possible and here’s why it is necessary.

Our negotiated agreement was approved and passed by both parties, not only because of the bargaining team’s work, but also because of all the members who wrote a letter and wore a T-shirt and attended a meeting and made their voices heard. Every show of solidarity makes a huge difference.

How can “rank-and-file” members support their local?

JG: If we all do small things, together we make big changes. I am so excited because of how many people got involved and saw that we can really move the county council with our collective voice.

Learn More About Educator Voice

Students and student-centered issues are at the heart of NEA’s bargaining, organizing, and engagement efforts. A growing number of locals engage in labor-management collaboration, a formal process of shared decision-making between educators and administrators. Whether or not states currently have collective bargaining rights, collaborative practices have helped educators raise their voices and achieve important wins such as:

- Educator participation in decision-making committees at the school and district levels.

- Improved teacher evaluation processes.

- Better discipline policies for students.

- Transparency among stakeholders in times of crisis.

Find out more at nea.org/collaboration.

People & Places

Meet The People Making News in Education.

Meet the 2022 NEA Human and Civil Rights Award Winners

Celebrating Champions of Justice, Inclusion, and Academic Freedom

When elementary school teacher Turquoise LeJeune Parker checked out at her local Costco in December 2021, her grocery bill tallied $103,079.70. The staggering figure was not an error. This was the actual amount she spent to buy food for families in her Durham, N.C., school district, so they wouldn’t go hungry during winter break.

The story of how she ended up with a hundred grand to help needy families goes back to 2015. That’s when a student’s family came to her for help because they didn’t know how they were going to eat during winter break. She soon learned that thousands of students in her district relied on school meals and faced hunger during school vacations.

She had to find a way to help. So she launched the Bull City Foodraiser. It started as a small project to help students in Parker’s class, but today the fundraiser serves more than 5,000 students in her district who receive free or reduced-priced lunches.

For this work and more, Parker was honored in June with the Reg Weaver Human and Civil Rights (HCR) Award. The award is named after a classroom elementary school teacher and former NEA president who was known for paying out of pocket to buy a student a winter coat, a meal, or school supplies.

Celebrating Diverse Cultures

Adriana Abundis, a high school, dual-language math teacher in San Antonio, earned the George I. Sánchez Memorial Award for her inclusive approach to bilingualism and biliteracy as well as academic success and social-cultural competence.

Abundis is a founding teacher and organizer for the dual-language program at Sydney Lanier High School, where her students are celebrated for mastering two languages and two cultures. She also developed the high school’s first Mexican American studies course and a dual-language middle and high school algebra curriculum for the district.

To make math more relevant to her students, Abundis engaged them in a yearlong challenge to create a 2,500-square-foot mural in their school’s neighborhood. The unit was rooted in civic engagement, art therapy, and real-world math application. At the end of the project, students regarded math as something they could create with their hands and hearts.

Protecting Academic Freedom and Faculty Rights

In 1968, the United Faculty of Florida (UFF), which represents the state’s higher education faculty members, was born out of the fight to protect academic freedom, defend civil liberties, and end racial discrimination at the University of Florida (UF). Since then, it has remained a vigorous and effective agent for academic freedom and faculty rights. And that is why UFF was honored with the Rosena J. Willis Memorial Award.

In fall 2021, UF administrators prohibited three UFF members from testifying in a lawsuit brought against the state of Florida to challenge a new voter suppression law. UFF organized to call out this violation of freedom of speech and academic freedom, demanding that the university reverse its decision. The university backed down. And, after hearing from the professors, a judge struck down the law. The activism of UFF members directly influenced the university and enabled this important win for Florida voters.

Teaching Inclusively

At the start of her teaching career nearly 30 years ago, Connecticut’s Valerie Bolling went beyond teaching lessons in poetry and championed diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). As a Black woman, she would comb the libraries for books that reflected her experience and that of her students, the majority of whom were People of Color.

Years later, a former student reached out to her. “I want you to know that YOU had a HUGE influence on us all,” the student wrote. “Having a Black woman as a teacher and role model early on in our lives … brought attention to topics that we would have never addressed.”

Today, as an instructional coach for the Greenwich school district and an author of children’s books, Bolling continues her work in DEI.

In 2021, a far-right community group stirred up public outcry against teaching an honest and accurate education. The group sought to defame Bolling by attacking her character and reputation in the community and in children’s literature circles. These actions of intolerance and intimidation did not deter Bolling, and she continues to work steadfastly to celebrate the voice and agency of all students. For dedicating years to DEI, Bolling earned the H. Councill Trenholm Memorial Award.

Championing gender equity

Sarah Milianta-Laffin, who teaches in Ewa Beach, Hawaii, set out to become a science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) teacher to help increase the number of girls and students of color in these classes. When she started teaching, in 2017, about 75 percent of students in her science classes were boys.

After much networking with local elementary schools, attending career day presentations, and bringing students to speak at school board meetings, almost 50 percent of her students are now girls.

Her work on gender equity in STEM goes beyond the classroom, too. After a student was bullied for bleeding through clothing during a menstrual cycle, Milianta-Laffin worked with her student clubs to start a free menstruation station” on campus. All students can now get free period products if they need them.

This spring, Milianta-Laffin and her students worked with Hawaii State Representative and former teacher Amy Perruso to pass a state law requiring public schools to provide free period products in bathrooms. For her work in gender equity, she earned the Mary Hatwood Futrell HCR Award.

Honoring An Education Activist, Gone Too Soon

Jorge González of Kings Mill, Ohio, seemed to do it all. A husband, father, passionate advocate for students, and committed educator of 34 years, he taught high school Spanish, and served as a coach as well as a diversity and inclusion coordinator. He also organized blood drives and trips to serve children in Latin America.

Tragically, González’s life and career were cut short on October 18, 2021, when he died after a brief battle with COVID-19. He is being honored posthumously with the NEA President’s Award for his activism and dedication to public education.

As a strong unionist, González served for eight years on the Ohio Education Association (OEA) Board of Directors. He advocated for students and educators on several legislative issues, and once led a march to the Statehouse to protest high stakes standardized tests.

He also worked to ensure diversity within his own union and was one of the founding members of the OEA Hispanic Caucus, where he served as treasurer.

The Kings Mills community and the OEA Hispanic Caucus have created a scholarship fund to help continue his legacy.

— Brenda Álvarez

57th Annual NEA Human and Civil Rights Awards

Call for 2023 Nominations

Know of an individual, organization, or affiliate that champions racial and social justice and civil rights within their community? Support their good work through a nomination for a 2023 Human and Civil Rights (HCR) Awards. Honorees are recognized during the annual HCR Awards program, held in July prior to the NEA’s Representative Assembly.

Help us:

- Identify and honor exemplary individuals, organizations, and affiliates for their contributions to human and civil rights, racial justice, and social justice.

- Celebrate NEA’s multicultural roots and commitment to justice.

- Recognize today’s human and civil rights victories and chart the path forward.

- Honor the rich legacy and history of the American Teachers Association (ATA) and NEA merger from whence the HCR Awards program began.

The work of civil rights and social justice heroes is as critical today as it was yesterday. Let’s work together to remind everyone that the cause endures, the struggle goes on, and hope still lives!

Identify your nominees now! It is never too early to begin profiling nominees and potential HCR Award winners! Find information on past winners at nea.org/hcrawards.

Nomination forms and instructions for the 2023 HCR Awards will be available on Oct. 11 to Dec. 5, 2022, at nea.org/hcrawards.

For more information, please email [email protected].